Visual Arts/Film Review: “Elliott Erwitt — Silence Sounds Good” — Far From Dull

By Peter Walsh

Aside from making generalities about “making good photographs” and “earning a living,” celebrated photographer Elliott Erwitt steadfastly refuses to be drawn out.

Elliott Erwitt — Silence Sounds Good, directed by Adriana Lopez Sanfeliu. Streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

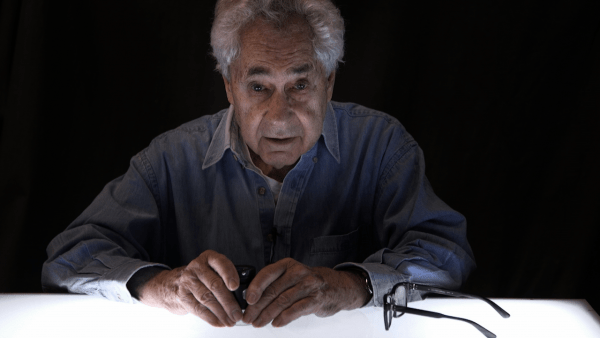

Photographer Elliott Erwitt in in a scene from Elliott Erwitt — Silence Sounds Good.

There are many challenges to making a documentary film about a living artist. First up, the filmmaker has the subject matter looking over her shoulder the whole time. Whose “artistic vision” will prevail? The subject matter is almost always in competition with the work.

Concerned about artistic reputation, public image, or legacy, the subject may veto interviews with ex-spouses, former colleagues and classmates, less-than-adoring relatives, or disapproving critics. Chunks of career or personal life may, implicitly or explicitly. be put off limits. Access to working and living space may be restricted. What’s left as an option is too often bland hagiography: a plaster saint surrounded by a chorus of praise-singing cardboard angels.

Director Adriana Lopez Sanfeliu faces another sticky issue in her film Elliott Erwitt, Silence Sounds Good. Despite her repeated efforts, she is unable to get her subject matter, photographer Elliott Erwitt, to say more than a few sentences about himself, his life, his photography or what makes him tick as an artist. Evasive to the end, Erwitt finally caps his spare answers with the observation “silence sounds good.” As a title, the phrase quite neatly sums up his approach to being in the film.

Although Erwitt’s name might not ring a bell, you probably will recognize his many well-known images that appear in the film: classically composed black-and-white photographs of sixties celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Jack Kennedy, and the young Fidel Castro (at one point, Erwitt remarks that making photographs of famous people “is more practical” because they are more likely to be published), bemused social satire, biting visual commentary on segregation, or amusing candids of dogs.

Erwitt’s career launched in an era when still, black and white photography played a role not too unlike the Internet today. Published in large-format, mass-circulation, glossy magazines like Life, Look, and Ebony, photographs like Erwitt’s were everywhere: on coffee tables, in dentist’s waiting rooms, and displayed on the racks of the then-ubiquitous newsstands. The most famous images made frequent appearances on television and in newspapers. Photographs of celebrities and national events drove movie star careers, set fashion styles, changed the course of political campaigns, and influenced public opinion on national issues like Civil Rights and the Vietnam War.

There was also, at that time, a social-class divide, going back to the origins of photography, when many fine-art photographers were wealthy amateurs. Making money from photographs was, in some circles, a bit disreputable. As photography struggled to be taken seriously as an art form, lines were drawn in the neighborhood. Art photography, the kind shown in museums and art galleries, should be free of commercial considerations and control. Like other artists after the Romantic Movement, art photographers had to be free to set their own aesthetic standards, to choose their own subject matter, and to follow the medium wherever inspiration led them.

Elliott Erwitt and director Adriana Lopez Sanfeliu at DOC NYC, 2019. Photo: Cargo Film Press

Erwitt landed firmly in the other camp: “cameras for hire.” News, commercial, and fashion photographers worked for clients, went where those clients wanted them to go, and took the photographs the clients were willing to pay for. Although the lines were never as firmly drawn as some made out, (Erwitt exhibited work in museums and galleries as well), the split, in Erwitt’s day, was a firm division of not just camps and priorities but aesthetic priorities as well.

Erwitt went a step or two further in his business interests. He has been a member of Magnum, the elite photographers’ cooperative, since 1954, invited by the organization’s founder, Robert Capa. The film features his spacious atelier with its spectacular views of Central Park and his small professional staff, including Lopez Sanfeliu, who worked as his assistant. Some in this inner circle have been with him for decades. In the film, we see them assembling one of his many books, working with his well-organized archives, and managing a work trip to Cuba to reprise one made decades earlier. Despite his avuncular personal style, Erwitt, in his late eighties as the film is shot, is clearly very much still in charge of his career.

But what does that career mean to him? Aside from making generalities about “making good photographs” and “earning a living,” Erwitt steadfastly refuses to be drawn out. A famously witty man, he uses jokes to deflect Sanfeliu’s questions. At one point, she tries to get his views on balancing career and life, using as an example her own dramatic shift in priorities once she became a mother. “I never considered becoming a mother,” Erwitt quips, leaving the actual question unanswered on the table.

Erwitt has been married four times but only his first wife (Lucienne Van Kan) is even mentioned in the film and she is never even named. His son by Van Kan appears as an infant with his mother, in one of Erwitt’s most famous photographs (USA, New York City, 1953, which was included in the celebrated Museum of Modern Art exhibition and book, The Family of Man) but the son, too, is left unnamed, and no siblings appear in the film or are mentioned there. We are left with the impression that, whatever his relationship with family members has been, his career always came first.

ELLIOTT ERWITT, SILENCE SOUNDS GOOD. Trailer. 2019. 62′ from Cargo Film & Releasing on Vimeo.

Erwitt is equally reticent to talk about aesthetic matters though his fierce commitment to them is made very evident in the film. His work has affinity with the photographs of Berenice Abbott and Diane Arbus: clearly focused, brilliantly composed images, always in black and white, that often capture strange or bizarre moments that seem to diagnose broader social themes. Many images breathe a sharp-edged commentary, as in his famous USA, North Carolina, Segregated Water Fountains (1950), which has been reproduced again and again to illustrate the harsh and absurd conditions of America’s Jim Crow Era segregation. Erwitt’s personal affections though are, in the film, largely limited to his warm relationships with dogs, the subject of many photographs and books. On one of the Cuba trips in the film he meets, makes friends with, and ultimately adopts a dog belonging to a Cuban family, so as not to “break its heart” by leaving it behind.

Despite such formidable challenges ,the film nevertheless soldiers on. The lush cinematography contrasts its brilliant, saturated palette with the formal black-and-white of Erwitt’s images. Erwitt’s work is reproduced clearly and effectively and the deft editing does wonders with filling in, without words, the points Erwitt mentions but does not elaborate upon. Lopez Sanfeliu‘s persistent questions and narration, which often seems to hint at things she can neither describe herself or get Erwitt to talk about, holds together a film that might otherwise have dissolved into fragments. The result, possibly partly because of these tensions, is far from dull.

Between takes, you can sense a strong, guiding hand that is not necessarily the filmmakers. Many biographical documentaries fill in missing details with interviews with long-time friends, family, and associate. Here the third-party voices are few and have little to add. Interviewees speak cautiously, as if watching for Erwitt’s reactions off camera. Despite his considerable charm and jovial demeanor, we gradually come to understand that Erwitt’s control here is as iron as in the rest of his career. He may well have to pass from the scene before a more definitive treatment of his life and work can be achieved.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 80 projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Tagged: Adriana Lopez Sanfeliu, Cargo Film, Elliott Erwitt, Elliott Erwitt -- Silence Sounds Good, Magnum