Film Review: “Jazz on a Summer’s Day” — A Contrarian View

Jazz on a Summer’s Day (1959), directed by Bert Stern. Releasing to virtual cinemas today. Available for streaming from the Brattle & Coolidge Corner.

This is not a music documentary, it’s a kind of jaunty-artsy immersion in and around the Newport Jazz festival, including scenes of the host city Newport, the America’s Cup race, festival goers, kids in playgrounds, etc.

Given how little attention has been paid to putting jazz on film, it makes a kind of addled sense that the first full-length documentary (more or less) about jazz should turn out to be the weird admixture that is 1959’s Jazz on a Summer’s Day.

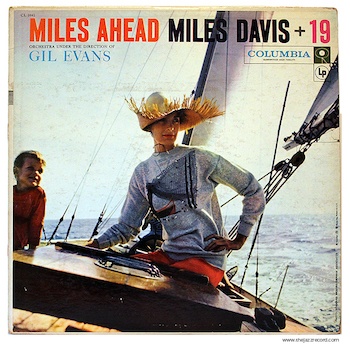

It was 1958, the age of Madison Ave. Madmen and the Playboy lifestyle. The producers’ declared intention for this documentary was to usher jazz out of the noir shadows and into the technicolor light. This was the period when haute advertising design was being mobilized for jazz album covers; GQ and Esquire were venerating the sartorial choices of Miles Davis. It was, to some degree, an uneasy match — an unease well symbolized by the conflict generated by the 1957 album cover of the LP Miles Ahead. The record was produced by George Avakian of Columbia records — who would have a lot to do with Jazz on a Summer’s Day. Miles hated the cover and he forced Avakian to change it.

Facts about the inception of the film are somewhat thin on the ground, but the idea to make it apparently came from Jean Stein, daughter of Jules Stein, president of M.C.A., the huge booking corporation for musicians and entertainers. She brought it to Bert Stern, first-time director, who was a well-known magazine and advertising photographer. Stern knew nothing about jazz (or film making, as it turned out), but had been hired by the patrons of the Newport Jazz Festival Elaine and Louis Lorillard (tobacco money) to shoot stills of the festival. Stern got festival producer George Wein’s cooperation, signed on Columbia Records principal George Avakian as Music Director, and his brother Aram Avakian as film editor. Stern’s agent came up with the initial money. Apparently, musicians were willing to sign releases, though it’s not clear how this important hurdle was surmounted. One wonders (1) how the juice was applied and (2) if any musician ever saw royalties from the film.

Stern’s first idea was to make a love story with jazz as the backdrop and the publicity for the film used romance as its focus, with the tag line: “…a picture that’s high on happiness…long on longing.” Posters showed the head of a man and a woman, looming large over yachts and a stage. This idea was dropped fairly quickly, probably because Stern had almost no experience in film and none in developing or shooting scripts.

According to Avakian, the first evening of documentary filming was a complete disaster and ”The morning of the second day, Bert simply turned the filming over to Aram.” It was the last film Stern was ever to “direct.” Aram Avakian recalled: “There were no full-fledged special cameramen around” and he himself had never handled a 35-mm camera before. In the end, five cameras shot over a hundred thousand feet of film and the editing process took six months. Aram Avakian said: ‘We went up to Newport with ten thousand dollars to make a short film on the festival. We ended up with a subjective documentary-feature of a public event.”

That’s not a bad description. This is not a music documentary, it’s a kind of jaunty-artsy immersion in and around the festival, including scenes of the host city Newport, the America’s Cup race, festival goers, kids in playgrounds, etc. There are lovely abstract shots of the water itself and impressive aerial shots of the flotilla of boats participating in the regatta. A lot of the initial money must have gone into rental of a Piper Cub airplane to get these shots, but it’s really the best way to shoot yacht porn, especially when the cameraman’s only previous camera experience was shooting out of airplanes in WWII (Bert Stern).

The festival audience gets a lot of airtime. Not that there aren’t interesting people in the audience. One famous long-held shot is of a woman in a red sweater chewing gum furiously, who turns out to be Patricia Bosworth, biographer of Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, and Diane Arbus. I spotted John LaPorta, Gerry Mulligan, and other musicians in the seats. There’s another young woman who is engrossed in a paperback of Camille; her presence explained by the fact that she was Bert Stern’s girlfriend at the time.

There are shots of a house party showing people (all white folks) actually gettin’ down with cans of beer, dancing on roofs, and making out on window sills. There is also a funny bit with the waiter who is serving the beers trying to stem the foam on the Reingolds he’s serving and spitting out the suds he can’t contain. Unfortunately, the verisimilitude of these scenes is undermined by the fact that they were not shot in Newport, but weeks later, on Long Island.

While the music is the raison d’etre for the film, there is probably as much footage of all this as there is of the music.

We see some music shot outside the festival itself, including a “Dixieland” combo, Eli’s Chosen Six (Yale guys) which reappears several times during the film. They drive through town tailgating in an old convertible, playing “The Saints.” They also ride on kiddie cars at the fairgrounds, stand at the waterfront, and drive away at the end in their jalopy, playing “Oh Christmas Tree” while the credits roll. Let’s hear it for a Trad leitmotif.

There is one unassailably cool music scene shot in a Newport house of a sweaty, bare-chested Chico Hamilton rehearsing his band. This may be the only musical scene in the film that’s allowed to play out without any cutaways. Later the camera comes back to capture Hamilton’s cellist Nathan Gershman playing a Bach suite in the shadowy chiaroscuro of an apartment. I suppose it wasn’t deemed romantic enough in itself and we break away often from Gershman playing to see kids cavorting innocently on a playground and shots of a solitary wanderer by the sea.

As noted, there are, in fact, some great musical moments from the festival. The music under the credits, which leads us to the first music onstage, is the Jimmy Guiffre Trio with Bob Brookmeyer and Jim Hall. The whole thing is a two shot of Guiffre and Brookmeyer. It’s a well-framed shot but, oddly, it is locked down (Critic Nate Chinen says all 5 cameras were handheld, but that’s not true — only 2 were) so that when either of the two musicians moves his head, the head simply goes out of frame. The only time we see guitarist Jim Hall is after the song ends and he walks into the tight frame.

In the next festival music scene we watch the audience while Willis Conover, of Voice of America fame is heard in voiceover introducing Monk. Of course, when he says: “Henry Grimes and Roy Haynes remain onstage to accompany Thelonius Monk…” we don’t know why they were already on stage. In fact, they had just been playing with Sonny Rollins, who is not in the film. The Monk scene lasts for one song — “Blue Monk,” but there are only two brief shots of musicians — one of Grimes and one of Monk. These play at the beginning and are repeated at the end, with almost all the scene taken up with boat and crowd shots. One can only speculate as to why there’s so little coverage of the musicians. The idea of running out of film is possible, but there are theoretically five cameras available for coverage and it would mean they brought only one under-loaded camera to the Monk set.

That brings us to the question of which musicians got filmed. According to Chinen: “This particular year George Avakian made an arrangement to record all of the artists on the bill, to ensure some measure of consistency.” There is precedent for this, as Verve seems to have locked up the festival rights in 1957. “On the other hand, Burt Goldblatt says: “No less than four record companies taped segments of the festival.” This is borne out by the fact that Atlantic released a Ray Charles at Newport 1958 record. Columbia released albums from Ellington and Brubeck at Newport 1958, which include both live music and music recorded later in the studio. There is another Columbia album with a Miles live set from Newport ’58 on one side and Monk at Newport in ’63 on the other. It’s agreed that Avakian told Stern which artists to film (actually, his brother Adam, who’d replaced Stern). George Avakian made his choices, he said: “on the basis of likely clearance and approval.” This is cryptic. How did it affect which artists were chosen for the film?”

[Note: There are non-Columbia musical tracks listed at the Library of Congress website (only available for in-person listening), which may have come from Conover’s Voice of America. And there is audio of Newport 1958 at Wolfgangs.com, with copyrights attributed to Bill Graham Archives and affiliates (Graham’s real name was Wolfgang Grajonca). I asked Wolfgangs.com and they replied: “We acquired the large bulk of Newport Jazz and Folk recording archives from Festival Network in 2009 (I believe), who previous to that had acquired those archives from George Wein’s original company Festival Productions.” That doesn’t clear up anything. It just shows music moving from one corporation to the next, as it increasingly does.]

Singer Anita O’Day, elegant in plumed hat and black dress, impeccably performs “Sweet Georgia Brown” and “Tea for Two.” She had gotten a lot of bad press about her recent narcotics incarceration and her Newport appearances helped rejuvenate her career. It beggars the imagination that they cut away so often to the crowd, which for much of the set seems only slightly involved, especially one young women who happily chomps down on a hot dog.

One of the odd musical choices George Wein made for the festival was to have Big Maybelle (a blues belter) and Chuck Berry both backed up by a band consisting of Jo Jones, Jack Teagarden, and other jazzmen. During the Berry number “Sweet Little Sixteen,” clarinetist Rudy Rutherford makes as close to a honking solo on clarinet as he can manage. There were delicate negotiations with the city of Newport about allowing rock and roll at the festival and this seems to be Wein’s way of trying to keep things from getting out of hand. Apparently, he warned Berry against wiggling his hips, but he still managed to incite the crowd-in a relatively subdued way.

It’s hard not to notice that the more challenging (cerebral?) jazz came from Guiffre and Gerry Mulligan’s groups, while the black acts were squarely in the “entertainment” category: Louis Armstrong, Big Maybelle ,and Dinah Washington. George Shearing is shown with one of his Latin groups. More challenging black musicians who also played the festival but don’t show up onscreen are: Miles with Coltrane, Ellington, Max Roach with Booker Little, Mary Lou Williams playing solo and the Randy Weston Trio. Chico Hamilton, whose band appears and might also be considered “serious” rather than “entertaining,” is mixed race. Also not seen are the Dave Brubeck Quartet, Willie “The Lion” Smith, Joe Turner, and Ray Charles.

Sonny Stitt blows in one scene, although he is actually seen on screen very little, given the numerous cutaways to boats and spectators. Chico Hamilton’s group has Eric Dolphy on flute (he takes a brief, simple solo) and John Pisano, guitar. Hamilton and Pisano are the focus and the shooting is nice, with a minimum of distracting cutaways.

Louis Armstrong tells a couple of amusing anecdotes to Willis Conover and then plays “Up a Lazy River,” “Tiger Rag,” and then he and Jack Teagarden perform their fabulous version of “Rocking Chair” uninterrupted. Then, Pops takes a quick spin with the “Saints.” Overall, they give Armstrong his due. Coincidentally, the only problem the Avakians say they had in getting permissions from musicians was that Armstrong’s representatives demanded he get $25,000, which they paid.

The final act of the movie — and of that day of the festival — is gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, whose set was purposely delayed until after midnight because she did not want to perform on the same day as the other, “secular” acts. Jackson is wonderful and the crowd responds vociferously to her performance, including breaking out into some suspiciously secular dancing. It’s the final act of the night, so it makes structural sense to program it here, but it seems odd that — after a day filled with beer-drinking, making out, dancing, and other frivolous acts — that the film ends this way. I suppose the surrounding hedonism is ameliorated by the fact that we had cut from Louis Armstrong doing the “Saints Go Marching In” into Mahalia’s set and then cut out of her set to the Dixieland guys riding in their jalopy playing “Oh, Christmas Tree” under the closing credits. As I say, Jackson’s performance is great, but as an ending to the movie it plays weirdly, like the Public Service Announcements your top 40 radio station ran on Sunday mornings, urging you to go to church; a call to piety sandwiched in between ads for Adventure Car Hop and Prince spaghetti.

And yet, this all seems fitting in a movie that my grandmother might call “a mishugas” — germinated in the overripe soil of the cultural elite and imbued with Madman stratagems, spoils, and treason — aka, the feathery brush of a light whitewash. When I watch Armstrong and Teagarden express a millennium’s worth of life experience and jazz wisdom, I’m deeply grateful, but I would trade all of the saturated color and all the screen time of sleek yachts and happy partiers for just a few more minutes of unadulterated Stitt, Monk, or for the chance to see Booker Little solo with Max Roach. There is beauty here, but there is also a subtext that will surface in the 1960 Newport Rebels Festival, organized by Charles Mingus and Max Roach. Apart from Eric Dolphy with Chico Hamilton and Jo Jones backing Chuck Berry, none of those rebels appear in Jazz on a Summer’s Day.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Great writing, Steve, and though I sensed many of these paradoxes, I always just dug the film as it was. But, as you show, there is much to be questioned and thought about critically. Despite all, the moment when Mahalia says “You make me feel like a star,” and then sings “The Lord’s Prayer” makes me cry like a baby.

Thanks, Dan. Yes, Mahalia is something else.

I will add that, as you reminded me elsewhere, the great Roswell Rudd was a member of the Trad group “Eli’s Chosen Six,” that played in the movie but who, unfortunately, could not make it when they filmed.

>> I would trade all of the saturated color and all the screen time of sleek yachts and happy partiers for just a few more minutes of unadulterated Stitt, Monk, or for the chance to see Booker Little solo with Max Roach.<<

Oh gawd yes. I hate this movie. I’ve always hated it. It was the first “jazz movie” I ever saw when i was still just a kid, and I hated it even then. The people who want to see the jazz being played do not care about the little kids and the white fraternity brothers drinking beer. The people who want to see the little kids and the white fraternity brothers drinking beer do not want to see Thelonious Monk. It’s a movie for people who enjoy watching rich white people mostly ignoring the great jazz geniuses.

I’ve struggled with a lifelong aversion to Anita O’Day because of her insufferable performance in this movie. I can’t hear her on records without thinking of her smugness in that big hat and gloves. Gloves!

The Armstrong section is the best thing about this sad film. So much incredible potential wasted in exchange for absolutely nothing.

A friend sent me photos of a poster of the film “Jazz on a Summer’s Day” signed by many of the principals. Under “A Bert Stern movie”, George Avakian wrote: “He’s a fucking liar” and Aram Avakian signed it: “Aram Avakian -the director and editor.” (he underlined (“director”).

An important time capsule, I’ll comment later however since I’m in New Orleans borned in New Orleans ground zero of the “ONLY” American art form, in thrilled to hear see Mahalia,Pops..and totally unfamiliar with Teagarden… I’m grooving stuck in because of COVID-19, what a respite

To those who do not like the film, what a bunch of whiners! You should just be happy the film was made and captured what it did. There was not much precedent for making any such concert film in 1958.