Classical CD Reviews: Philip Glass, “Music in Eight Parts,” Thomas Adès, “In Seven Days,” and Anna Clyne, “Dance”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Music in Eight Parts is a welcome and inviting addition to the Philip Glass canon; the Summer of Thomas Adès continues with a stirring new recording of the British composer’s keyboard work; Anna Clyne’s Dance is, without a doubt, one of the finest pieces I’ve heard this year.

Philip Glass’s Music in Eight Parts is a piece that almost got away: written in 1970, the score disappeared a few years thereafter, only turning up at a Christie’s auction in 2017. Salvaged and slightly rescored, it was slated for a series of performances this past spring by the Philip Glass Ensemble before the coronavirus pandemic shut down concert life.

The group’s new recording of the piece, though, took advantage of the isolation situation, with each of the five performers – vocalist Lisa Bielawa, saxophonists Peter Hess and Andrew Sterman, and keyboardists Michael Riesman and Mick Rossi — contributing their parts from their respective home studios. Stitched together by Riesman, the result is a tight, bracing dose of vintage Glass.

If Music in Eight Parts sounds familiar, it should. Written between Glass’s Music in Fifths and Music in Changing Parts, the score is firmly rooted in his early mature body of work, with an emphasis on subtle shifts of rhythm and counterpoint. The piece follows, roughly, a slow-fast pattern, its materials gradually and discreetly transformed over its 20-minute duration. And, while there’s plenty of repetition involved in Glass’s technical language, there’s a clear dramatic trajectory to his writing here that seems to foreshadow the seminal Music in 12 Parts (1971-74) as well as his theater works of the ’70s, ’80s, and beyond.

Ultimately, then, this is a welcome and inviting addition to the Glass canon. Even if Music in Eight Parts isn’t a major work (as Glass seems to suggest) it’s a captivating and concise snapshot of his music in its freshest, most vital, and most inventive period. Performances and engineering leave nothing to be desired.

The Summer of Thomas Adès continues with a stirring new recording of the British composer’s keyboard works (the second such of the last couple of months) featuring the dynamic keyboardist (and Adès muse) Kirill Gerstein. Gerstein is a brilliant musician and Adès’s intellectually and expressively demanding music consistently draws forth his best.

In 2010’s Three Mazurkas, for instance, Gerstein ably teases out the music’s subtle nods to Chopin – the first movement’s lilting figures, the second’s delicate, improvisatory-sounding melodic line – while also embracing Adès’s varied reference points, from François Couperin to Conlon Nancarrow. Perhaps the reading’s finest moments come in the grimly serene finale, with its implacable spacings and soaring melodic writing.

Gripping, too, is Gerstein’s account of the hazily sober “Berceuse” from Adès’s 2018 opera The Exterminating Angel, which receives its premiere recording here.

Also making its record debut on this album is the four-hand piano version of the Concert Paraphrase from “Powder Her Face.” Adès’s 1995 opera is raucously inventive and the current piano reduction gives it a thoroughly Lisztian – which is to say, bonkers – treatment.

Gerstein and the composer (who joins him on the recording), though, are never at a loss: the whole piece is voiced with incredible clarity. What’s more, its densely superimposed dissonant rhythmic patterns are articulated with astonishing precision. Taken with the performance’s supreme command of the music’s sensuous undercurrents, you’ve got a reading that’s both bracing and great fun.

Rounding out the disc is a new recording of In Seven Days, Adès’s 2008 piano-and-orchestra meditation on creation stories. The piece is highly evocative: its materials are tightly unified and ingeniously transformed; as a result, the score holds together with remarkable coherence. Even so, its traditional inner logic never sounds (or feels) passé.

The present recording features Adès conducting the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra (TMCO), which delivers a generally lively account of the orchestral part. Some tentativeness at the beginning and spotty intonation here and there notwithstanding, theirs is a reading that seems to have a lot of fun when called for (see the woodwind and brass figures in the “Stars – Sun – Moon” movement), and, often enough, is lucidly textured (no more so than in the wild “Creatures of the Sea and Sky” fugue).

Throughout, Gerstein delivers a commanding performance of the solo part and, if there’s some peripheral audience noise to be had moment-to-moment, the larger reading is intense, exacting, and well balanced.

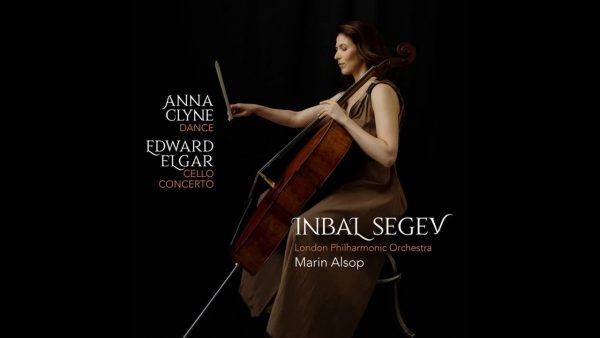

Anna Clyne’s Dance is, without a doubt, one of the finest pieces I’ve heard this year. A cello concerto based on a Rumi poem, its five movements follow the injunctions of the verse: dance, it says, “when you’re broken open/…if you’ve torn the bandage off/…in the middle of the fighting/…in your blood/…when you’re perfectly free.”

Clyne has responded to these lines with a piece that sings unabashedly and constantly. Her writing in Dance’s five movements (each one takes as its subtitle one of the above lines) is unfailingly lyrical. What’s more, the piece is entirely lacking in pretension and feels, for its entire 25-minute duration, like an utterly natural musical statement.

Dance’s first movement presents a high solo cello melody floating over, essentially, block chords in the orchestral strings. In the second, drone-like figures and exotic-sounding flourishes (augmented seconds and the like) pass between solo cello and orchestra; indeed, the exchange of foreground and background materials between the two is striking.

The third and fourth movements feature chaconne-like structures, though the latter involves more elaborate variations on the melodic line. In the finale, Clyne reprises several themes heard in earlier movements; after several interruptions of the songful themes, Dance’s final statement – a gracious, soulful tune – ultimately wins the day.

Clyne wrote Dance for cellist Inbal Segev, who presents it here with a compelling sense of ownership. All I can say is that her account of the solo line is impeccable; one can hardly imagine it played with greater conviction or intensity.

Marin Alsop leads the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) in a tight, fervent accompaniment. A couple of questionable second-movement doublings of the solo cello line aside, Dance is a flawlessly written piece and its debut recording is simply lovely. With Osvaldo Golijov’s Azul and Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Cello Concerto, it ought to be a 21st-century cello concerto staple.

Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto, which fills out the disc, is a standard but from the 1900s. In her reading, Segev’s got all the notes in hand, which is no mean feat. But her interpretation only skims the surface of this score: the whole needs to be dug into more deeply (or, in the case of the second movement, let loose a bit more). Ultimately, Segev doesn’t take the big, necessary risks with Elgar’s score that’s demanded.

So it’s a bit of a missed opportunity, then.

But there are many great recordings of the Elgar to console yourself with. There’s only one of Dance and it’s a doozy of a piece – don’t miss it.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Anna Clyne, Avie, Inbal Segev, Kirill Gerstein, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Marin-Alsop, Music in 8 Parts, Myrios, Orange Mountain Music, Philip Glass