Jazz CD Review: “The Jerry Granelli Trio Plays Vince Guaraldi and Mose Allison” — Paying Exciting Homage

By Michael Ullman

The interpretations of the covers in this beautifully realized tribute album will bring back memories of the originals in a way that is enlivening rather than nostalgic.

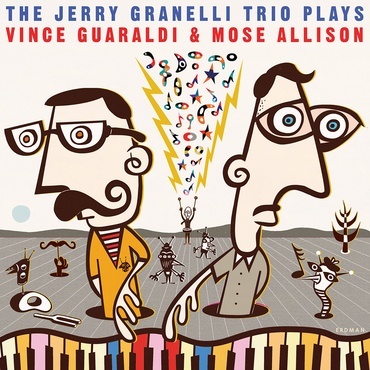

The Jerry Granelli Trio Plays Vince Guaraldi and Mose Allison, featuring Jamie Saft and Bradley Christopher Jones (Rare Noise Records)

There was a time during the late ’50s and ’60s when a carefully crafted jazz tune, if it was sufficiently short and (usually) sweet, could become a hit. In real life, this meant that my non-jazzy friends might know, among others, “Take Five,” “The In Crowd,” “Georgia on My Mind,” a Stan Getz bossa nova like “The Girl from Ipanema,” Count Basie’s “April in Paris,” and Vince Guaraldi’s “Cast Your Fate to the Wind.” Some of these performances — I am thinking in particular of “Cast Your Fate” — were so distinctive that it takes courage as well as talent to successfully cover them. As he demonstrates in his new album, drummer Jerry Granelli meets both requirements. And he has the perfect trio for the task: a pianist in Jamie Saft who has a large warm sound as well as a lyrical bent that doesn’t prevent him from eloquently playing free jazz and, in Bradley Christopher Jones, a tactful yet playful bassist whose lovely, expressive sound is enhanced by a knack for choosing the apt note.

There was a time during the late ’50s and ’60s when a carefully crafted jazz tune, if it was sufficiently short and (usually) sweet, could become a hit. In real life, this meant that my non-jazzy friends might know, among others, “Take Five,” “The In Crowd,” “Georgia on My Mind,” a Stan Getz bossa nova like “The Girl from Ipanema,” Count Basie’s “April in Paris,” and Vince Guaraldi’s “Cast Your Fate to the Wind.” Some of these performances — I am thinking in particular of “Cast Your Fate” — were so distinctive that it takes courage as well as talent to successfully cover them. As he demonstrates in his new album, drummer Jerry Granelli meets both requirements. And he has the perfect trio for the task: a pianist in Jamie Saft who has a large warm sound as well as a lyrical bent that doesn’t prevent him from eloquently playing free jazz and, in Bradley Christopher Jones, a tactful yet playful bassist whose lovely, expressive sound is enhanced by a knack for choosing the apt note.

They open with what is perhaps their biggest challenge, “Cast Your Fate.” In the wake of Guaraldi’s success the tune was played by the likes of Herb Alpert and sung by dozens, including Mel Tormé (in one of his most kitschy recordings). None of these erased the indelible resonance of Guaraldi’s catchy, instantly memorable performance. Granelli’s version begins out of tempo, with Saft slowly introducing the melody in a gently refined manner over the bowed bass of Jones. Saft slows down the song’s distinctive phrase, which accompanies the lyrics “cast your fate.” He is paying tribute to the Guaraldi original while at the same time offering a wholly appealing alternative. The performance gathers in intensity, as Saft improvises until he offers a rhapsodic ending over Granelli’s brushes. The rendition ends via a kind of gently wandering coda. The conclusion was very much in the spirit of the lyrics, which tell of a daring young sailor who lets the wind (I am aware this is metaphorical) decide where he shall go and what he shall do. He is old and disappointed when he finally arrives at his destination. Granelli, unlike other performers who have taken on the tune, goes out of his way to note that melancholic ending.

The trio is also celebrating the music of a white boy who swiped the blues, Mose Allison, whose 1958 song “The Seventh Son” was a hit, at least on the radio stations I listened to. (I bought a mono LP version from 1963: Mose Allison Sings.) There’s nothing quite like the quick-moving chatter and rattle of an Allison performance, in which his patter, puns, and wit are married to an up-to-date, bopping piano style. His pieces tended to be short, over as soon as you began to relish them. They were memorable and controversial. As soon as he released his “Seventh Son,” he was accused of ripping off the blues. He answered in a song that’s on his 1989 album, My Backyard: “Have you heard the latest news … it’s even going to make the TV news: A white boy steals the blues.” Thanks to his theft, no one, not even a guy whose baby left him, can have the blues anymore. They’ve been taken away.

Born in Mississippi, Allison earned a degree in English and philosophy. His lyrics are funny: “Your mind is on vacation and your mouth is working overtime,” he chants, while elsewhere noting in a manner that is relevant today: “Everybody’s crying justice/ Just as long as there’s business first.” He was an efficient, no-nonsense artist: when I heard him none of his songs seemed to last longer than the three minutes that would fit onto a 45. Granelli zestfully plays “Baby Please Don’t Go,” one of the blues Allison stole from Big Joe Williams. It’s been played by dozens of blues singers but, because of its stuttering melody line, it isn’t a natural (I would think) for a jazz performance. Allison made it work and Granelli turns the tune into something like a New Orleans march. The trio plays the blues zestfully: the interaction between Saft and Guaraldi on drums is brisk and alert, and that brightness continues even into Jones’s bass solo.

Allison had a hit with “Parchman Farm,” a tune named after the infamous Mississippi prison farm. His version is not closely related (by design) to the infinitely touching blues by ex-prisoner Bukka White, who sang “ I wouldn’t hate it so bad but I left my wife…. Goodbye wife, all you have done done/ but I hope someday you will hear my lonesome song.” Working at Parchman Farm meant that the sun became your enemy: “We got to work in the mornin’, just at dawn of day (2×) Just at the settin’ of the sun, that’s when the work is done.” Allison’ s version isn’t as bleak, but then he was never imprisoned: in the first chorus he is sitting and thinking his predicament over. He makes an old country joke: “I’m going to be here for all my life…and all I did was shoot my wife.” (Another version goes: “Ninety-nine years is almost for life/ And all I did was shoot one wife.”) Granelli’s version of “Parchman Farm” focuses on the song’s insistent rhythm. In fact, he uses the key change that Allison employed. The trio once again delivers an exciting performance, paying obvious tribute to the original while incorporating its own buoyant rhythms and original style of playing the blues.

The band inserts two original pieces that they call “Mind Prelude Number One and Number Two.” Played by Jones in duet with Granelli, “Number Two” reminds this listener of Muddy Waters’s “Got My Mojo Workin’.” The disc ends with a tune from Guaraldi’s score for A Charlie Brown Christmas. In the movie, it’s rather a sober song, as Charlie Brown, whom his sister declares is the “Charlie Browniest” person alive, doesn’t feel the holiday spirit all around him. Granelli’s version is darker — and dare I say tenderer — than Guaraldi’s. Like the other covers in this beautifully realized tribute, the interpretation will bring back memories of the original in a way that is enlivening rather than nostalgic.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Mose Alliso, Rare Noise Records, The Jerry Granelli Trio

Great tribute, got to work with both on bass back in the day. Thx,Nick

Looks wonderful. Do we know if it was an analog or a digital recording or any details about the production/engineering credits?