Film Commentary: Movie Love or, Seven Moments from the Ontology of the Cinematic Image

By Patrick Pritchett

The anti-cinema, represented by CGI, obliterates perception; it is not interested in tutoring the eye to see more deeply.

In his essay “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” French film critic André Bazin lays out a convincing account of what sets film images apart from all previous instances of pictorial representation. “Only a photographic lens,” he argues, “can give us the kind of image of the object that is capable of satisfying the deep need man has to substitute for it something more than a mere approximation.… the photographic image is the object itself, the object freed from the conditions of time and space that govern it.” Bazin’s influential conception of the film image is almost mystical. He envisions that the power of the cinematic image is liberated (impossibly) from the director’s framing. It is as though the lens itself were solely responsible for delivering us to the real.

In our current era of blockbuster filmmaking, we’ve grown habituated to being bludgeoned by the gigantism of motion pictures. Outside a few rare practitioners, such as Terence Malick or Steven Soderbergh, massive spectacles of destruction line up to assault us. They are symptomatic creations of what Bazin calls elsewhere “the Nero complex,” filmmakers who are obsessed with visual bombast. The anti-cinema, represented by CGI, obliterates perception; it is not interested in tutoring the eye to see more deeply. The paradox is that some of the greatest moments in the history of film are compelling because they are about withholding, holding back. They draw on the discretion of the camera, on the appeal of sly inference.

At the same time, it should be kept in mind that all filmmaking, even the most naturalistic (think Ford, Renoir, De Sica) is a form of special effect, and that the greatest special effect ever devised in the movies remains the close-up. Here, in no real order, are moments from a few of my favorite films, movies that I have watched over and over again, each time with a renewed sense of wonder at the possibilities of cinema.

Kathleen Byron in a scene from Black Narcissus

Black Narcissus | Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger | 1949

Perhaps the most erotic movie ever made? The vertiginous vistas of the Himalayas, the heavy virginal drop cloth of the nun’s habits against the outrageous, psychotropic palette of a jungle Eden — all contribute to what must be one of the most visually sumptuous experiences the movies have to offer. There are many scenes one could point to as breathtaking.

Here’s one: Sister Ruth (the exquisite Kathleen Byron) after she’s become unhinged by her lust for Mr. Dean (David Farrar), the local agent and all-round hunk. The scene is sunset: drenched in otherworldly, beatific light. Sister Ruth’s face is a study in brooding madness. An Indian boy has just entered her chambers with a glass of what he calls lemonade, though it looks like milk. Sister Ruth disdainfully chases him from the room. Suddenly she hears voices and, swirling around, rushes to the window. Below her, in the courtyard, her superior, Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), and Mr. Dean, are conversing. We cannot hear what they are saying. Ruth frantically chases through the halls of the monastery (a former seraglio) to catch further sight of them. Because of the high angle, they assume, in her gaze, a conspiratorial air.

The scene ends with Farrar and Kerr stopped on a terrace above a frightful abyss. Kerr is pouring her heart out and Byron, blown against the latticework, is spying down upon them – an infernal triangle. All this while Kerr stands stiff and straight, her face a play of wry, sad, ironic reflection. As a subdued pastoral score plays over the scene, she tells Dean about her lost love in Ireland, about why she entered the order, about how she found peace – and about how, after coming to the Himalayas, all the old ghosts are being stirring up. “I couldn’t stop the wind from blowing and the air from being clear as crystal, and I couldn’t hide the mountain.” Amazingly, nearly all of Black Narcissus was made on a sound stage at Pinewood. Shot by the legendary Jack Cardiff (who rightly won an Oscar for his work), with art direction (or what would now be called production design) by Arthur Junge, Black Narcissus glows with a profane radiance. It is a triumph of artifice and the beauty of color and light, — there’s nothing else like it.

The Third Man | Carol Reed | 1949

Screenwriter and novelist Graham Greene once remarked that he thought audiences simply wouldn’t sit still for the long closing take in Reed’s masterpiece. He eventually changed his mind. The scene is Vienna’s cemetery, where Harry Lime has been laid to rest yet again, this time for good. On the way to the airport, Major Callaway (Trevor Howard) and Joseph Cotton’s fool for love Holly Martins pass Harry’s old flame, Anna (the sublimely aloof Alida Valli), walking the long road back. Martins insists that Callaway let him out. “Be sensible, Martins.” “I haven’t got a sensible name, Callaway.” He hoists his duffel bag and saunters over to a wagon loaded with wood to wait. Anna is a dark tiny figure dead center in the background, moving ever so slowly toward us. Reed shoots her straight on, at about shoulder height, with Cotton in the left foreground, staring vacantly at nothing. Anton Karas’s somber, melancholy zither score seems to encourage the brittle leaves to fall from the nearly denuded trees. It takes about a minute for Anna to approach Holly and, when she does, she pays him not so much as a glance. There’s only one cut, near the start of her walk: Callaway’s slightly disgusted over-the-shoulder look at Martins before he pulls away. After Anna passes him, Martins shakes loose a cigarette, lights it, and disdainfully throws the match to the ground. The audacity of Reed’s decision to hold that shot for so long, defying expectations, stretching out the tension, underlines Greene’s sour worldview. In the age of disaster, there can be no happy endings. “Poor Crabbin,” writes Greene in the short novel (based on his screenplay). “Poor all of us when you come to think of it.”

Close Encounters of the Third Kind | Steven Spielberg | 1977

In my SciFi film class, I screen the above scene of a pilot’s near collision with a UFO to illustrate how much tension can be generated using the most minimal of means. This early short sequence lasts only 3-and-a-half minutes. There are several things going on. First, there’s the conduct of the air traffic controllers as they try to wrap their heads around the unprecedented. This is Spielberg at his most Hawksian. Even in the face of the unbelievable, the controller’s professionalism never wavers. The dialogue is mostly technical: questions about the UFO’s appearance (“the brightest anti-collision lights I think I’ve ever seen”) and instructions on what kind of evasive maneuvers to take (“Area 31 maintain flight level, break, Allegheny triple four turn right 30 degrees”). Second, the camera almost never moves. There are two or three pans to the right, which allow extra players to converge into the tight frame already established, and a few cuts from the master shot to a close-up of the radar screen. But that’s it. The scene begins with two controllers, but by the end of it contains six or seven men, all crammed into the same visual space. Talk about traffic control. At one point Spielberg takes a page from Robert Altman, using overlapping dialogue: the timing and the sound mix are flawless. Third, the entire incident is depicted solely through a radio conversation between the tower and the pilots, with only the sharp green lights of the controller’s radar screen indicating action. The tension is built on what we don’t see, set up by Spielberg’s masterful staging. (There are approximately 20 cuts in this scene: a few pans to bring new characters into the frame, one over-the-shoulder shot of the main controller, and extreme close-ups of the radar screen to indicate the positions of the planes. Nothing fancy, extraneous, or showy.)

Not long ago, Soderbergh paid homage to his brilliance by setting Raiders of the Lost Ark to the The Social Network soundtrack and deleting all the dialogue. You can view it here. The results are astonishing.

A scene from Bringing up Baby.

Bringing Up Baby | Howard Hawks | 1938

Scripted by the great Dudley Nichols, this may well hold claim as the apogee of screwball comedy. Which is saying a lot, considering Hawks’s other entries, Ball of Fire and His Girl Friday, or Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels and The Lady Eve, to name just a few competitors. Cute meet: the hapless paleontologist David (Cary Grant), in full tux and tails, comes to a posh restaurant looking for his wealthy patron, Mr. Peabody, when Susan (Kate Hepburn), dressed in a slinky, shimmering silver outfit, literally trips him up with a martini olive. Comedy ensues. As the slightly spastic Dr. Lehman advises Susan, “The love impulse in men very frequently reveals itself in terms of conflict.” What follows goes well beyond your classic comedy-of-misunderstanding; this is barely masked sexual frenzy revealed through slapstick. First Hepburn rips Grant’s dinner jacket as he tries to exit up a stairway: “Oh, you’ve torn your coat.” Then Grant steps on Hepburn’s luminous gown, splitting it open up the back and exposing her lacy undergarments. Grant frantically tries to cover up her exposed derrière by clapping his phallic top hat over the tear. As symbolic fucks go in the Code era, it doesn’t get better than this.

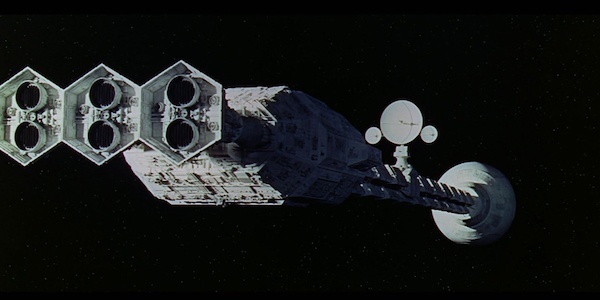

The Discovery spacecraft in 2001.

2001: A Space Odyssey | Stanley Kubrick | 1968

We first see a shot of deep space, without any context. Then a title card: “Jupiter Mission, 18 Months Later.” The slow mournful chords from the adagio of Khachaturian’s “Gayane” come up. Slowly, from the left side of the screen the nose of the Discovery pushes into view (in reality, the camera is tracking backwards along the length of the 18-foot model). The globe of the living quarters is at first cut off at the top, as if it’s too big to fit on the screen. It is a move that George Lucas would lovingly copy 10 years later in the opening scene of Stars Wars and that has been emulated by numerous SF films, including James Cameron’s Aliens. (Probably the best homage is Brian De Palma’s underrated Mission to Mars, which makes use of some amazing zooms, swirling and inverted, through spaceship windows.) Kubrick also includes balletic shots of floating bodies in space, glimpses of what Annette Michelson calls, in what is still the best essay on 2001, “the structural potentialities of haptic disorientation as agent of cognition.” The ship moves forward, stately, imperturbable. The globe’s volume is amplified by the smaller radio array of the AE-35, a satellite dish mounted on the fuselage. Finally, the engines heave into view – and we cut to a reverse angle so we now see the ship moving past us — from the front still cruising left to right. Then cut again, to a middle-distance shot in which the ship, seen from its side, stretches across the frame. In every shot, the vehicle fills the screen. Time elapsed: roughly a minute-and-a-half. During that period we are transported by the eerie floating alien grace of interplanetary flight, a new form of the technological sublime.

Terence Stamp in The Limey

The Limey | Steven Soderbergh | 1999

The Limey is a classic revenge picture and one of the best “sunshine noirs” of recent vintage. Wilson, an English thief fresh from prison, has come to America looking for his daughter, Jenny. Soderbergh has described this film as a combination of Get Carter and Hiroshima Mon Amour. And it is. The opening sequences manipulate time brilliantly. Is Wilson just arriving in L.A.? Or is he on the return flight to London, musing about all that’s occurred? The first lines we hear, while the screen is still black, are Wilson’s, played by a loose, Cockney-slanging but wire-coiled Terence Stamp: “Tell me. Tell me. Tell me about … Jenny.” But it’s not until the film’s climax that we realize these are the final lines he speaks to her killer, the sleazy record producer Terry Valentine (the perfectly cast Peter Fonda).

Through an intricate series of cuts, past, present, and future fluidly overlap until the difference among them is erased: Wilson, brooding on the plane (Stamp’s shriven skull – stark, solemn, and hallowed); Wilson smoking on his dingy hotel bed; Wilson buying guns from two teenage gangbangers in a park. Interspersed among these scenes are repeated shots of Wilson striding in slow-motion determination along a sun-drenched brick wall, dressed all in black. Soderbergh shoots the scene from a distance, at a low angle, so that Wilson appears small against the industrial background. The classic law-of-thirds composition is slightly distorted here: the thin strip of asphalt and the concrete base of the building appear as one level; the massive red brick of the windowless wall another; and the washed out blue of the sky, cloudless and remote, as the third. He’s a small figure, almost puny – but utterly determined to wreak his vengeance.

My Darling Clementine | John Ford | 1946

The anecdote has taken on the sheen of myth. When asked who his favorite filmmakers were, Orson Welles replied: “the old masters, by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.”

In the mid-’40s, Ford made three of his greatest films, each of them documenting the rituals of isolated and embattled communities trying to survive at the edge of the frontier. Taken together, Clementine, Fort Apache, and They Were Expendable pay homage to the cultural logic of Manifest Destiny. In My Darling Clementine, Ford’s heavily romanticized version of the Wyatt Earp story, civilizing Tombstone involves more than the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. It also takes a “dad-blasted good dance,” as Russell Simpson, part of Ford’s stock company, puts it. Ford liked to say that his two favorite things to shoot were horses at full gallop and couples dancing.

The dance in Clementine begins with a ritualistic walk as Henry Fonda escorts Clementine (Cathy Downs) down the boardwalk to the town church, which turns out to be nothing more than a wooden platform and the scaffolding of a belfry. In the distance, the townsfolk can be heard singing “Shall We Gather at the River.” Ford shoots this scene with great solemnity and circumspection, the camera discretely tracking the pair at a middle distance as they stay framed inside several receding rectangles formed by the boardwalk, the wooden awning, and strips of sunlight and shadow. They could almost be walking down the aisle of a medieval cathedral. The couple pauses at the edge of the crowd. Downs glances over at Fonda expectantly, while the actor, looking as uncomfortable as a man can when called upon to do the chivalric thing, removes his hat, fidgets with it, then finally tosses it aside. “Oblige me, ma’am?” he almost whispers. As soon as they mount the platform, Simpson calls a halt to the music, crying out, “Sashay back, and make room for our new marshal, and his lady fair!” What follows is a moment of pure joy as Downs and Fonda perform a high-stepping waltz, surrounded by a clapping crowd. Fonda’s stiff-legged, storklike dance step would be laughable, were the expression on his face not so radiant.

Ford’s orchestration of what could have been a prosaic scene is flawless: one of the truly transcendent moments in American film.

Patrick Pritchett has been writing about film and literature since 1990. Before entering the academic world, he worked in script development for James Cameron, Kathryn Bigelow, and Jay Cocks. He is the author of numerous essays on American poetry and several books of poems, most recently Orphic Noise and the forthcoming Refrain Series. He has taught at Harvard University and Hunan Normal University in China. Currently he is a lecturer at the University of Connecticut-Hartford and Southern Connecticut State.

Tagged: 2001: A Space Odyssey |, Bringing Up Baby, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Patrick Pritchett, The Limey

Thanks for a delightful read with great reasons to revisit this diverse selection. Watching Clementine as a kid on New York’s Million Dollar Movie, I thought the way Cathy Downs removed her jacket – in contrast to Fonda’s elegant reticence.- was the just gosh darn sexiest, sweetest thing I’d ever seen.

Shall We Gather by the River was certainly a Ford favorite and use many times:

https://tinyurl.com/yaalotfj