Opera Album Review: The Most Neglected Master of Opera? Carl Maria von Weber, Early and Late

By Ralph P. Locke

New recordings of Peter Schmoll and His Neighbors and of Euryanthe pose an embarrassing question: why is the opera repertory so narrow?

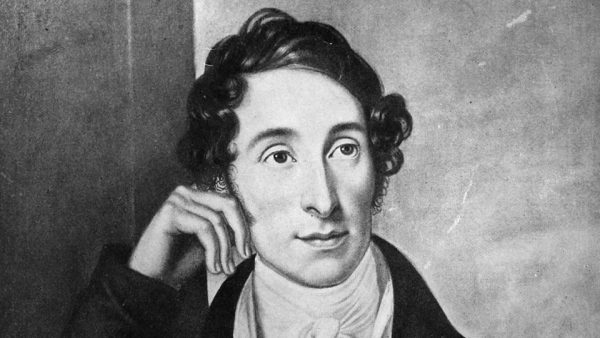

Composer Carl Maria von Weber — time to restore him to the eminence he once held in musical life.

Carl Maria von Weber: Peter Schmoll and His Neighbors (Peter Schmoll und Seine Nachbarn)

Ilona Revolskaya (Minette), Sebastian Kohlhepp (Karl Pirkner), Paul Armin Edelmann (Peter Schmoll), Christoph Seidl (Hans Bast), Thorsten Grümbel (Martin Schmoll), Johannes Bamberger (Niklas)

ORF Vienna Radio Symphony, cond. Roberto Paternostro

Capriccio 5376—80 minutes

Weber: Euryanthe

Jacquelyn Wagner (Euryanthe), Theresa Kronthaler (Eglantine), Norman Reinhardt (Adolar), Andrew Foster-Williams (Lysiart), King Ludwig VI (Stefan Cerny)

ORF Vienna Radio Symphony, Arnold Schoenberg Chorus/ Constantin Trinks

Capriccio 5373 [2 CDs] 160 minutes

There have been many complaints in recent decades about the narrowness of the opera repertory. Major opera houses have responded, to some extent, by putting on operas from before Mozart (e.g., by Handel); by reviving forgotten works by Mozart, Rossini, Donizetti, or Verdi; by making space for new works by such composers as Thomas Adès, Gerald Barry, Mason Bates, Philip Glass, Nico Muhly, Tobias Picker, Kaija Saariaho, and Jeanine Tesori; and by mining the treasure-house of operetta and musical comedy: works by Offenbach, Lehár, or Rodgers and Hammerstein. (The Sound of Music will be performed this summer at Glimmerglass, in upstate New York. The resplendent mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard plays Maria. It then moves to Houston Grand Opera, where, in a bold case of race-blind casting, the role will be taken by the Trinidadian soprano Jeanine De Bique.)

Yet some great operatic efforts continue to be ignored, perhaps none more regrettably than those by Carl Maria von Weber. Weber features prominently in any historical account of the history of German opera, since his Der Freischütz (1821) provides such a perfect “stepping-stone” from Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Beethoven’s Fidelio to the operas of Wagner. The whole genre of German Romantic Opera is generally (and justly) described as beginning with works by Weber and, at a lower level of musical inventiveness and dramatic viability, Ludwig Spohr and Heinrich Marschner, culminating in Wagner’s first three masterpieces: The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin.

Der Freischütz is the one Weber opera that gets performed regularly in German-speaking lands, and thus exists in many marvelous recordings, including notable ones conducted by Joseph Keilberth and Carlos Kleiber. But it appears rarely on the performance schedule of opera houses elsewhere (e.g., at the Met), surely in large part because it is a Singspiel — that is, a work whose numerous musical numbers (arias, duets, etc.) are separated by pages, sometimes, of spoken dialogue. Speech, as I have pointed out in my review of his final opera, Oberon, does not project well in large opera houses. (The Met seats 4000, and its acoustics can be a problem in seats under an overhang.) Speech is also a problem when an opera house’s cast members come from widely divergent parts of the world and thus are rarely all able to speak the requisite language with an actor’s skill, for example, with appropriately varied pacing and inflection.

Weber wrote eight or so operas, despite dying at the age of 39. (This includes a few that were left unfinished or survive incompletely.) Most of them are known today primarily for their overtures (e.g., the marvelous Abu Hassan and Oberon). I have previously drawn attention here to his final two operas, Euryanthe (in a marvelous historic broadcast featuring the young Joan Sutherland) and the aforementioned Oberon (his one English-language opera, in an extremely effective German-language version, with a narrator replacing the spoken dialogue).

Two recent releases gave me occasion to relisten to Euryanthe, now with some of today’s most proficient singers, and to his very first opera, Peter Schmoll und seine Nachbarn, of which I had previously known only the overture. (Both recordings can also be streamed at Spotify, Naxos Music Library, and YouTube.) I came away from the experience with even greater admiration for Weber’s mastery of harmony, of the lyrical vocal line, of characterful musical description, and of fresh orchestral combinations and contrasts. Each opera poses its own challenges for our opera companies: spoken dialogue, in the case of Peter Schmoll (and most of Weber’s other operas), and the problem of how much to trim the exuberantly overlong Euryanthe (long in part because everything in it is sung, which always stretches things out). But each work would greatly enrich an operagoer’s experience, and each of these recordings, in its own way, helps restore Weber to the eminence he once held in musical life.

Both recordings come from the Theater an der Wien, which is located in central Vienna. (The Wien River, at whose banks it sat, now flows under the streets.) The theater dates back to the days of Beethoven, who for a time lived upstairs from the hall. Its compact size — 1,129 seats — makes it very appropriate for works from the early 19th century, not least in allowing cast members to be heard easily.

IIlona Revolskaya, soprano, who sings the role of Minette in Peter Schmoll.

Weber was 15 when he composed Peter Schmoll und seine Nachbarn (first performed 1803), but already proficient and imaginative. He had good teaching from one of the most skillful composers of the day: Johann Michael Haydn, brother of Joseph. (I loved a recent recording of a Johann Michael opera: Die Wahrheit der Natur, “Nature’s Truth.”)

Peter Schmoll is in many ways a typical comic Singspiel of its day, filled with short arias, duets, and trios. Many arias are relatively simple or folk-like in style and strophic in form. I was reminded of the songs and duets involving Papageno in Mozart’s aforementioned Magic Flute, first performed 12 years earlier.

Most notable, perhaps, is the extravagantly colorful orchestration, with solo passages for various wind instruments in number after number: piccolo, clarinet, bassoon, a pair of rambunctious horns, and so on. In the beleaguered soprano’s first aria, her final melodic phrase is followed by a flute solo without any accompaniment at all: surely a musical metaphor for her isolation and vulnerability. This attention to the winds would find fuller expression in the rich orchestral textures of Weber’s later operas. It also points, in a way, to the numerous fine works Weber would go on to write for clarinet.

The plot draws on standard comic stereotypes and situations. What we get here is a substantial but very effective reworking by Willy Werner Göttig that was published in 1963. I will describe it. (Interested readers can find the original texts for the musical numbers online. Some of the characters and dramatic interactions are different in the original.) A young woman, Ninette, has been raised by her uncle (Peter Schmoll), who wants her for himself. Her father Martin Schmoll and the young man that she loves, Karl, have been reported dead. In the end, Karl and Minette’s dad reappear. Thanks to some timely intervention by Peter’s servant Hans Bast, Peter realizes the error of his wishes and allows the young lovers to marry. (Hans is, in dramatic function, somewhat analogous to Mozart’s and Rossini’s Figaro, though at times comically slow-witted, whereas Figaro is largely portrayed as an effective mastermind.)

The recording offers all of the opera’s musical numbers but nothing to connect and motivate them. (The original spoken dialogue does not survive and would not, in any case, have worked with the retexted musical numbers.) What we hear comes from two unstaged performances, and the singers, nearly all native German-speakers, convey the dramatic course of events very effectively. The orchestra sounds small but well drilled (except for occasional sour tuning in the wind section). Christoph Seidl, as the servant Hans, has a voice too light on the low end—the role clearly requires a comic bass. Otherwise, the singing reveals numerous nuances in the score and never approaches caricature.

This seems to be only the second recording of Peter Schmoll, and it is a total delight. Alas, the reworked libretto is given in German only. The informative essay and performer bios are in German and (good) English.

(The previous recording was released on Marco Polo in 1994. It uses the same retexting by Göttig, plus spoken dialogue, and thus spills over onto a second CD. The booklet contains no libretto at all. The recording can be found, like the new one, at major streaming sites. Here’s the enchanting overture in the 1994 recording.)

Euryanthe came 20 years later (1823) and is worlds apart in mood and means. This was Weber’s sole attempt at writing what would come to be known as a “German Romantic opera”: a stage work that is sung all the way through and deals with a serious topic, usually involving figures from history or national legend. There were a few earlier or contemporaneous efforts at creating serious opera in German: for example, Holzbauer’s Tod der Dido, Beethoven’s Fidelio, and two major operas by Ludwig Spohr. But Euryanthe is the whole package, 20 years before Wagner. (Fidelio, despite its many wonders, remains somewhat compromised as an operatic experience. As noted earlier, spoken dialogue tends not to carry well, especially in a large theater. And, even if declaimed well, it can easily deflate the tension built up so successfully by Beethoven’s musical numbers.)

Euryanthe came 20 years later (1823) and is worlds apart in mood and means. This was Weber’s sole attempt at writing what would come to be known as a “German Romantic opera”: a stage work that is sung all the way through and deals with a serious topic, usually involving figures from history or national legend. There were a few earlier or contemporaneous efforts at creating serious opera in German: for example, Holzbauer’s Tod der Dido, Beethoven’s Fidelio, and two major operas by Ludwig Spohr. But Euryanthe is the whole package, 20 years before Wagner. (Fidelio, despite its many wonders, remains somewhat compromised as an operatic experience. As noted earlier, spoken dialogue tends not to carry well, especially in a large theater. And, even if declaimed well, it can easily deflate the tension built up so successfully by Beethoven’s musical numbers.)

I summarized the plot of Euryanthe — and noted its likely influence on the plot of Lohengrin — in my aforementioned review of an unstaged 1955 BBC broadcast performance that featured the young Joan Sutherland. Euryanthe is, opera scholars generally agree, richly inventive and often quite intriguing in its characterizations, its music for various contrasting dramatic situations, its recurring themes and motives, its harmonic language, and its orchestration. The overture is a familiar item from concerts and recordings. When its tunes return in the opera proper, I was delighted to find that they are often extended and varied in interesting ways. I should have expected this, given that Weber wrote many instrumental works (e.g., sonatas, symphonies, concertos, and a trio for flute, cello, and piano) that make proficient use of developmental procedures. I also noticed figurations and rhythmic patterns in the orchestra that I suspect influenced Berlioz.

Scholars and others familiar with the complete score generally admit that it is too long for its own good; Weber himself allowed whopping cuts to be made. Mahler made his own version, in an attempt at giving the work a life on stage.

The new recording is 160 minutes long; the BBC broadcast with Sutherland is 138 minutes; the fine studio recording conducted by Marek Janowski (Dresden, 1974) is 175 minutes; a 2002 staged-performance recording available on Dynamic and starring Elena Prokina clocks in at 155. These differences in length come in part from tempo decisions, but even more from cuts. For example, the BBC broadcast eliminates the enchanting series of dances in Act 3, one of which is in quasi-“old” style, a bit like Rameau.

I love almost everything about this new recording of Euryanthe. It comes from a run of performances in December 2018. To judge by the photos in the booklet and in a trailer for the DVD version, the staging—the costumes look like ones in a Grace Kelly–era Hollywood film—did little to convey some important cultural resonances in the work, which is set in 12th-century France. Fortunately, I need only deal here with the aural results.

Theresa Kronthaler (Eglantine) and Andrew Foster-Williams (Lysiart) in the 2018 production of Euryanthe. Photo: Monika Rittershaus.

Four of the five main singers were previously unknown to me but prove to be wonderful. All four have been cast in major roles in important European opera houses: Jacquelyn Wagner (whose other roles include Donna Anna, Vitellia, and Eva), Norman Reinhardt (Ottone, Belmonte, Pollione), Theresa Kronthaler (Sesto, Dorabella, Nicklausse) and Stefan Cerny (Leporello, Basilio, Sparafucile).

The fifth main singer, English-born and -trained Andrew Foster-Williams, sings with keen dramatic understanding. Unfortunately, when excited or trying to sustain long notes, he develops a wobble and loses pitch clarity. In the crucial bad-guy role of Lysiart, his voice cannot give suitable emphasis to many crucial low-lying notes and passages. Like the others, Foster-Williams has sung major roles in European houses (Don Pizarro, Kurwenal, Golaud). I imagine that he is a persuasive, even gripping presence on stage. Still, this is the third review in which I have felt obliged, in all honesty, to single him out as sounding overtaxed by a role’s basic vocal requirements. (See my reviews of Saint-Saëns’s Proserpine and Benjamin Godard’s Dante.)

As often in recordings made during a staged performance, the singers and orchestra (Austrian Radio Symphony) sound very much engaged. (Gorgeous brief solos from horn and bassoon.) The Arnold Schoenberg Choir is utterly magnificent. The work’s changing moods are vividly conveyed under Constantin Trinks, who has conducted at Seattle Opera and other prominent houses. Trinks’s frequent and convincing small shifts of tempo helped hold my interest in the proceedings. The offstage passages for instruments and chorus are, remarkably, in tune with the pit orchestra and the onstage singers.

Microphone placement was not always ideal. A few times a singer seems a bit distant, and my ear had trouble untangling the complex interweaving of voices in the Act 2 finale. Still, this one technical imperfection is small compared to the merits of the recording as a whole, which truly sounds like a performance and thereby makes a case for the opera as a viable stage work. Had the baritone been more strongly cast, this Euryanthe would have been on my “Best of the Year” list.

Jacquelyn Wagner (Euryanthe) and the Arnold Schoenberg Choir in the 2018 production of Euryanthe. Photo: Monika Rittershaus.

People interested in hearing a more perfect rendering, moment to moment, would likely prefer the aforementioned studio recording featuring Jessye Norman (in resplendent voice), Rita Hunter, Nicolai Gedda, and Tom Krause, or the aforementioned BBC broadcast with Sutherland, Marianne Schech, Frans Kroons, and Otakar Kraus. Sutherland displays rock-solid technique, but makes less of the words than Jessye Norman or, in the new recording, Jacquelyn Wagner

However you get to know it, Euryanthe is a work full of passion, character, variety, and — at least in these trimmed versions — much forward momentum. I even wonder whether Verdi knew it: I noticed possible anticipations of “Amami, Alfredo” in Act 1 and of “Quand le sere al placido” in Act 2.

The informative essay and synopsis are in German and awkward English (wisely uncredited). The synopsis contains a major mistranslation: it is not Euryanthe who elicits the secret about Adolar’s dead sister from Eglantine but the reverse. The libretto is in German only, but I located a decent old translation on the Internet. A gratifying plus: applause only at the ends of acts.

And, with luck, both these recordings will serve as a reminder to opera companies — large and not-so-large — about the many vital operas by Weber that we rarely or ever get to see on stage. Certainly some of the shorter operas, mainly comic in nature, would be well suited to the music-school opera programs and adventurous local companies such as Odyssey Opera. Abu Hassan, anybody? A comical folktale, nominally located in an Arabian Nights–type setting, it could be creatively located anywhere in the world, and would surely delight an audience, much as a famous recording with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf has charmed record collectors over the years. (A fine stereo recording, conducted by Bruno Weil, is less widely available.)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. He contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).