Opera CD Review: Carl Maria von Weber’s Wildly Assorted Candy Box — A Spiffy New Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

The rarely staged Oberon is easy to love and will fascinate admirers of early nineteenth-century music.

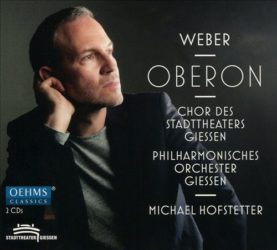

Carl Maria von Weber: Oberon

Dorothea Maria Marx (Reiza), Marie Seidler (Fatima), Dmitry Egorov (Puck), Mirko Roschkowski (Huon of Bordeaux), Clemens Kerschbaumer (Oberon), Grga Peroš (Sherasmin)

Giessen Philharmonic and Stadttheater Chorus, conducted by Michael Hofstetter

Oehms 984 [2 CDs] 112 minutes

To buy, click here.

Poor Carl Maria von Weber! He was one of the great opera composers, but he died at 39. Had he lived longer, he might have enriched the opera repertory with many important and imaginative works. Worse, two of his three richest creations — Der Freischütz and Oberon — are full of spoken dialogue, which makes them hard to perform in modern-day massive opera houses. This, however, makes them extraordinarily well suited to home listening (or in the car, or at the gym). In that sense, Weber may have been “ahead of his time”!

Poor Carl Maria von Weber! He was one of the great opera composers, but he died at 39. Had he lived longer, he might have enriched the opera repertory with many important and imaginative works. Worse, two of his three richest creations — Der Freischütz and Oberon — are full of spoken dialogue, which makes them hard to perform in modern-day massive opera houses. This, however, makes them extraordinarily well suited to home listening (or in the car, or at the gym). In that sense, Weber may have been “ahead of his time”!

Oberon, or the Elf King’s Oath (1826) was Weber’s last work for the stage (after the remarkable Euryanthe; see my review of the latter, with Joan Sutherland). I hesitate to call it an opera, because it is most peculiar by conventional operatic standards. Written for London and given its first production there, it belongs to a tradition that goes back to Purcell and his contemporaries: the semi-opera (or operatic “extravaganza”), consisting of a play with many highly contrasting spoken scenes that are interleaved with musical numbers, some of which involve secondary characters only. A version of this stage tradition continues in Britain today in the Christmas-season “pantomimes” about Cinderella, Robin Hood, or Ali-Baba and the forty thieves.

Weber’s work transported the audience member (delightfully? disconcertingly?) from one quasi-exotic locale to another—the fairy kingdom, France (under Charlemagne), Baghdad, and Tunis — creating occasions for colorful sets and costumes. In certain passages of the music, Weber intensified the “you are there” effect through Middle Eastern local color as imagined at the time, e.g., unison passages, odd chordal progressions, and “Turkish” percussion. In general, the orchestra is used with great originality, as lovers of the work’s long-famous overture know.

Recordings have used a variety of solutions: e.g., musical numbers separated by narration, or musical numbers plus shortened spoken dialogue spoken by actors rather than the singers. As a result, some important characters who only speak, never sing — such as Roshana, the jealous “other woman” in a love triangle — are not heard at all on, I believe, any recording. The work is done most often in German rather than the original English.

It rarely gets staged, and surely never in its original format, with acres of spoken exchanges and much magical flying through the sky at the behest of Oberon, king of the elves. Recordings have come and gone, and sometimes return again, as if conjured up by Oberon’s magic wand. I got to know it, years ago, from the 1971 recording, in German, conducted by Rafael Kubelik (still available), which features marvelous vocal performances, in German and not always in quite the right style, by Birgit Nilsson and a youngish Plácido Domingo.

There have been at least four other recordings, conducted by Marek Janowski, Eve Queler, James Conlon (using Mahler’s adaptation, which underpins certain passages of spoken dialogue with Weber-derived music, and John Eliot Gardiner. The Gardiner is sung in English, if with much mushy pronunciation, and is remarkable mainly for the distinctive sounds of the period-instrument orchestra (especially the very bucolic woodwinds). Jonas Kauffmann, in one of his earliest commercial recordings, performs the joyous, demanding, and oft-omitted Act 3 aria superbly.

The present release, sung in Theodor Hell’s highly effective nineteenth-century German translation, uses a spoken narration in German (often in rhyming verse) to set up each new scene and situation. The narrated bits are brief and are read with intriguing touches of mystery and humor by actor Roman Kurtz. Page turns and audience rustling suddenly become more evident when the narrator re-enters and the engineers re-balance the microphones.

The spoken summaries are sometimes located at the beginning of a track or in the middle of a longish one. This makes them almost impossible to skip. Indeed, some tracks include more than one musical number, thus hiding from the track list such important items as the exotic wind-and-percussion march in Act 2.

The release would have been more attractive to an international market if the booklet had at least provided texts in German and English. In the case of the musical numbers, the company could easily have printed the original English verses that Weber set, thereby enabling us to “hear” the music in our own language (or even sing along, a bit), as we listened!

The booklet essay is poorly translated and far too brief, not even informing us that the tenor’s aforementioned Act 3 aria of triumphal joy has been omitted and that his Act 1 aria has been relocated to the beginning of Act 2. The latter decision means that the exotically flavored ‘Glory to the Caliph’ chorus is delayed a bit: Weber intended this scene-setting number to welcome us, at the raising of the curtain, to the banks of the Tigris. The plot synopsis in the booklet is far too short, merely a teaser for the spoken narrations. The one in Grove (OxfordMusicOnline.com), by contrast, is detailed and fully reliable.

Carl Maria von Weber: One of the great opera composers, but he died at 39.

The recording, taken from performances (and perhaps some patch sessions) in December 2016 and January 2017, is spiffy, with singers — mostly native Germans — who have young, compact, and, for the most part, firm voices and who enunciate the text clearly and with good dramatic understanding. Mirko Roschkowski, as Huon, is capable, but sometimes smudges the coloratura—even short melismas as in this duet with Fatima. Dorothea Maria Marx’s warm but controlled tone draws one in. The role of the magical imp Puck, written for a female mezzo-soprano, is taken, with no historical basis whatever, by a (very fine) countertenor (Dmitry Egorov); the change, I must admit, nicely reinforces the weirdness of the scenes involving supernatural forces.

The smallish orchestra is well drilled and vividly recorded. Conductor Hofstetter often takes livelier tempos than did Kubelik, who was at times clearly responding to the special gifts and needs of Nilsson and Domingo.

The overall tone of liveliness and sharp detail is helped by the fact that the Giessen Municipal Theater is quite intimate, with at most 700 seats. Audience members are likely to feel more involved in such a cozy hall, easily seeing and hearing details that might go lost in, say, the Met (4000 seats). Indeed, loud, enthusiastic applause and some bravos follow many of the musical numbers. I got a clear feeling of being at a performance that had good shape and flow and a consistent spirit and style.

However one chooses to get to know it, Oberon is easy to love and will fascinate admirers of early nineteenth-century music. My own favorite numbers include a one-strophe song for the soprano heroine (Reiza, here Rezia), accompanied by nothing but a guitar (plus a magic-invoking prelude and postlude for winds); the same character’s extended, proto-Wagnerian aria “Ozean, du Ungeheuer” (“Ocean! thou mighty monster,” which American-born soprano Maria Callas recorded, using the original English words); and the Act 1 and Act 3 finales, which involve the chorus and develop in imaginative ways two different quirky and supposedly Middle Eastern tunes that had been made available in travel books.

Other listeners will no doubt have their own preferences. Weber’s score for this rather bizarre but endlessly engaging theatrical mess is like a box of mixed candies: chocolates with soft or chewy fillings, nut-covered caramels, fruit-flavored suckers, round peppermints…. Enjoy, and share with friends!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Tagged: Carl Maria von Weber, Giessen Philharmonic and Stadttheater Chorus, Michael Hofstetter, Oberon