Book Review: “Irving Berlin: New York Genius” — A Significant Life

By Benjamin Sears

Biographer James Kaplan was aided by the assistance of Irving Berlin’s two elder daughters, and that makes this biography particularly valuable.

Irving Berlin: New York Genius by James Kaplan. Jewish Lives, Yale University Press, 424 pages, $26.

Irving Berlin has long been a subject of interest for writers, their approaches ranging from the scholarly (Charles Hamm) to the fawning (Alexander Woolcott). In recent years, a spate of new studies and biographies have appeared, including histories of specific songs. James Kaplan’s Irving Berlin: New York Genius is a significant addition.

Kaplan approaches his biography by focusing on Irving Berlin as a Jewish New Yorker. As with all those writing on the composer’s life, he had to deal with vague, sometimes conflicting, stories about Berlin’s years before 1909 and his initial success as a songwriter, along with ambiguity about later happenings in his long life. Kaplan was aided by the assistance of Berlin’s two elder daughters, and that makes this biography particularly valuable. It is the first that draws on direct family input. Berlin was always his own public relations man; early on he created a version of his life for public consumption; those “facts” were used and reused over his lifetime, often making it difficult for a biographer to find new information, given the seemingly endless series of articles that essentially only retold the same story.

Kaplan negotiates the inevitable uncertainty well, often noting when it is hard to determine which alternative is true. Many Berlin stories, such as the meeting with George Gershwin or the evolution of the song Easter Parade, have differing versions. The biographer is forced to make choices. Berlin himself would often give different accounts of the same event, Easter Parade being one example. (For full disclosure, I edited the Irving Berlin Reader, in which I dealt with Easter Parade.)

As a Jew in America in the 20th century, Berlin inevitably suffered the effects of antisemitism. His courtship of Irish Catholic Ellin Mackay was met with disapproval and even obstruction on the part of her father, Clarence Mackay. In another example of conflicting stories, Berlin is said to have given Mackay one million dollars after Mackay lost everything in the stock market crash. Berlin daughter Mary Ellin Barrett, in interviews with Kaplan, firmly asserts that this was not true. Eventually, Berlin and Mackay were able to maintain a polite relationship.

The most virulent antisemitism aimed at Berlin was in response to God Bless America. Rev. Dr. Edgar Franklin Romig, minister of the West End Collegiate Reformed Church in Manhattan, felt compelled to sermonize on what he perceived to be the song’s shortcomings. Kaplan points out what the sermon was saying, via the coded language of the time: “The nerve of this Jewish songwriter!” He does not mention the virulent and uncoded attack on Berlin by Cleve Sallandar in an American Nazi publication, though he does cite the power of the antisemitic German-American Bund to draw a sizable crowd to Madison Square Garden in the years leading up to World War II. Berlin was by no means immune to this atmosphere of hate.

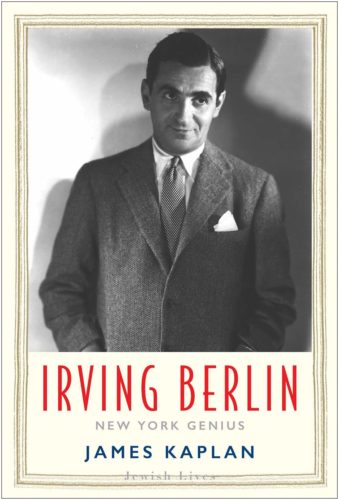

Composer Irving Berlin. Photo: Wiki Commons.

In contrast, Kaplan presents a different perspective on the Jewish immigrant experience in America. He highlights Berlin’s purchase of a country home in the Catskills. “This was the immigrant Jew’s Chekovian dream: his very own place in the country.” For a man who moved from a childhood of intense poverty in Russia to intense poverty in the U.S., yet managed to achieve financial stability, this homestead stood as a significant accomplishment.

While Kaplan does not place it in the context of the Jewish experience in America, he points out that Berlin’s army unit, which performed his World War II revue This Is the Army throughout the U.S. and in the American theaters of war in Europe and Asia, was the first integrated unit in U.S. history. Berlin never forgot his own experience as a member of a minority.

A famous Berlin story concerns his lunch with Winston Churchill in London during the war. Supposedly, Churchill thought he was dining with philosopher Isaiah Berlin. Berlin’s own account of the meeting makes it unclear whether Churchill really did not know which Berlin was his guest. Kaplan lets readers draw their own conclusion — without lessening the story’s amusing aspect.

Berlin’s last hit song was written in 1967, but the times had already passed him by. A 60-year run for any popular songwriter is an amazing achievement but, as Kaplan and others have pointed out, Berlin felt he had been forced into retirement, and he had a hard time adjusting. Kaplan is very sympathetic to Berlin’s last years, when those adjustments to retirement and old age could make dealing with him difficult. In her memoir, Mary Ellin Barrett is quite frank about how hard it could be to deal with her father in those last years; some, though, have simply presented Berlin as an angry, bitter old man. Kaplan describes these years in a way that helps the reader empathize with what life must have been like for Berlin — and that is an important service to the composer’s legacy.

Overall, while this biography presents Berlin as a Jewish immigrant living the Jewish experience in America, the volume also serves as a good introduction to the composer for the general reader. Given the complexities of the man’s personality, it is doubtful if any study could ever be considered “definitive.” However, every impartial recounting of his life and accomplishments only adds to our understanding of this significant figure in American popular music.

One final and lovely Berlin story from the book. “Once, when the three girls were young Ellin had chided Linda for putting her elbows on the dinner table. ‘Daddy puts his elbows on the table,’ Linda said. ‘Your father is a genius,’ Ellin replied, ending the conversation.” Yes, he was.

Singer Benjamin Sears, with pianist Bradford Conner, has been performing and recording Irving Berlin for thirty years. Their final Berlin CD in a series of seven is in process. Sears is editor of The Irving Berlin Reader (Oxford University Press). CDs of Berlin, and others, are available at www.benandbrad.com