Jazz Album Review: A Confidently Rousing “La Marseillaise” from Pianist Laszlo Gardony

By Michael Ullman

One of the strengths of Laszlo Gardony’s playing is his confident insistence on what he is doing, his impressive self-assurance.

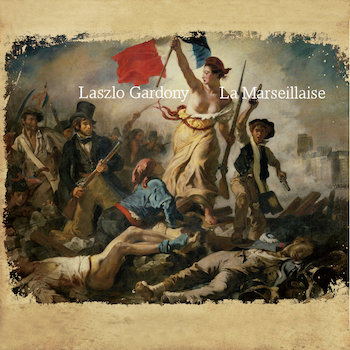

La Marseillaise, Laszlo Gardony (Sunnyside)

Interestingly, the French national anthem, La Marseillaise, has been exploited by composers from Rossini to Elgar, including most famously by Tchaikovsky, whose 1812 Overture is perhaps his most popular work. Still, and despite the fact that Django Reinhardt recorded the tune as Echoes of France — in an at first lachrymose and then perhaps excessively spirited version — it seems an unlikely vehicle for jazz improvisation. Three cheers, or perhaps salutes would be more appropriate, to the distinguished pianist Laszlo Gardony, who opens his new solo disc (recorded live on March 19 at Berklee College of Music’s Keys Fest) with Revolution, based on La Marseillaise. Gardony opens by hinting at, or moving around, the famous melody, making use of a loosely rhapsodic style. When it stomps, as he makes it toward the end of the first chorus, it sounds more bluesy than martial. Gardony’s big, two-handed style, with its fullness and richness of color, enables him to produce a pounding new piece out of an old chestnut.

Interestingly, the French national anthem, La Marseillaise, has been exploited by composers from Rossini to Elgar, including most famously by Tchaikovsky, whose 1812 Overture is perhaps his most popular work. Still, and despite the fact that Django Reinhardt recorded the tune as Echoes of France — in an at first lachrymose and then perhaps excessively spirited version — it seems an unlikely vehicle for jazz improvisation. Three cheers, or perhaps salutes would be more appropriate, to the distinguished pianist Laszlo Gardony, who opens his new solo disc (recorded live on March 19 at Berklee College of Music’s Keys Fest) with Revolution, based on La Marseillaise. Gardony opens by hinting at, or moving around, the famous melody, making use of a loosely rhapsodic style. When it stomps, as he makes it toward the end of the first chorus, it sounds more bluesy than martial. Gardony’s big, two-handed style, with its fullness and richness of color, enables him to produce a pounding new piece out of an old chestnut.

He follows with “O Sole Mio,” which I remember as the favorite song of sunburned retirees, at least in the ’50s. (Often it was sung in English with the title There’s No Tomorrow. Elvis did his own version, It’s Now or Never.) To Gardony, it’s a rich love song, bombast and sentimentality extracted. He starts with a heavy, yet deftly moving, left-hand pattern over which the melody, played with equal fullness, emerges. His improvisation is melodic and harmonically adventurous, thick in texture, its forward movement robust. One of the strengths of Gardony’s playing is his confident insistence on what he is doing, his impressive self-assurance. For the third number of the set, he evidently asked the audience to shout out four notes. He plays them, up and down the keyboard, and then begins an improvisation that is propelled by the same certainty, the same seemingly effortless mastery, with which he plays standards. This effort, though, exudes an exotic flavor dictated by the given notes. He continues with “Misty,” the most famous composition from the elfin wunderkind, Erroll Garner.

“Misty” is followed by a lesser known favorite, “Quiet Now,” which was introduced by its composer, pianist Denny Zeitlin, on his Live at the Trident album. (Zeitlin’s recorded it repeatedly since, as on his Homecoming album.) The tune became a favorite of Bill Evans, who recorded it at least a half dozen times, also usually live. Gardony’s version is more full-bodied, less wispy, than Evans’s typical rendition. He plays part of the first chorus with two-handed chords. The set winds up with three originals. I would guess that “On the Spot” was improvised at the venue. The melody for “Mockingbird” was most likely preset. Gardony concludes with a rocking favorite of his, which anyone who has seen him live has probably heard. It’s “Bourbon Street Boogie,” and it is treated (as always) as a joyous romp — a dance piece for those who love early jazz and its environs. Gardony has said that he thinks in terms of whole sets when he sits down at the piano in front of an audience. He hopes that listeners will pay careful attention to his overall musical vision. The variety, virtuosity, and sheer musicality found in this album make that a very easy challenge to accept.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.