Classical Music CD Reviews: Strauss/Korngold’s “Eine Nacht in Venedig,” Berlioz’s Requiem, and Ethel Smyth’s Mass in D

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Among the reviews: a terrific, important release that celebrates one of the most interesting – and hitherto overlooked – composers of the late-19th- and early-20th centuries in style. Don’t miss it.

After he was one of Europe’s greatest musical child prodigies and before he became the defining composer of film music for the 20th century, Erich Wolfgang Korngold found tremendous success repurposing the operettas of Johann Strauss II in post-World War I Europe. One of his great triumphs, a 1923 adaptation of Strauss’s 1883 semi-hit Eine Nacht in Venedig, is out in a new recording from CPO.

Korngold’s arrangement consists, essentially, of a tightening-up of Strauss’s original – cuts of and within individual numbers, plus insertions of music from other Strauss operettas – as well as a reorchestration of the score. There’s also a reworking of the libretto, though it’s essentially convoluted nature remains unchanged.

Venedig’s story is standard, labyrinthine operetta fare, following the machinations of a duke attempting to carry out a tryst with a beautiful woman he met at last year’s Carnival in Venice. Suffice it to say, nobody gets hurt and the operetta’s lesser characters end up in better economic circumstances than the ones in which they began the show.

The present recording features the Graz Opera Chorus and Graz Philharmonic Orchestra (GPO) under the direction of Marius Burkert. By and large their performances are strong and idiomatic. The chorus, especially, sings with vigor and heft, never losing sight of the dancing impetus behind Strauss’s writing.

Burkert’s tempos are all smartly judged and the GPO plays with a fine command of Strauss’s style, though some of Korngold’s embellishments – namely his harp writing – tend to dominate the orchestral texture more than they probably should.

The cast is fine, if not one to beat the starry 1954 recording of Venedig featuring Nicolai Gedda, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and Erich Kunz.

Lothar Odinius sings the Duke with commanding energy and intonation, though there’s nothing to really makes his account of the role stand out. In the same vein, Ivan Orescanin’s Pappacoda proves adequate, if a bit literal in his role.

On the plus side, Elena Puszta’s Annina is lovely, sung with a nice, light tone, on-point intonation, and wonderful diction. She’s got fine chemistry, too, with Alexander Geller’s Caramello, whose account of his involved part is winning (his Lagunen-Walzer is conspicuously excellent).

Throughout, the blend between principal characters is tonally solid. Also, the performance omits entirely the operetta’s spoken dialogue, which helps move the score’s action along.

Hector Berlioz’s 1837 Grand messe des morts hasn’t always been well-served on disc, which, given its spatial and personnel demands, isn’t perhaps surprising. A kind of visceral response to the Latin rite for the dead, it was meant to be experienced in – and is best served by – live performance.

Hector Berlioz’s 1837 Grand messe des morts hasn’t always been well-served on disc, which, given its spatial and personnel demands, isn’t perhaps surprising. A kind of visceral response to the Latin rite for the dead, it was meant to be experienced in – and is best served by – live performance.

That makes John Nelson’s new recording of the piece (with the London Philharmonic Choir and Philharmonia Choir and Orchestra) all the more impressive.

It’s not a technically flawless document: the cavernous environs of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral wreak havoc on both voices (the treacherous opening of the “Lacrymosa” sounds a bit untamed) and ensemble (woodwind detail-work in the “Offertorium” is diffuse).

But Nelson’s reading has a tremendous amount of heart to go along with an uncanny understanding of Berlioz’s style and a second-to-none feel for the structure of his music.

Throughout, there’s a terrific sense of rhythmic direction, attention to dynamic detail, and grasp of the music’s character. The “Dies irae,” for instance, is not only expertly balanced between the vocal lines, but carefully paced and, for all its tremendous climaxes, marked by textural lucidity: the low-string triplets in the “Judex ergo” speak with startling immediacy.

Similarly, the “Rex tremendae” gets a truly ecstatic reading, one that’s full of color and motion. It’s one that also takes advantage of the big performance’s big space, with the resonant blur between the “salva me” and “Rex tremendae” sections providing a touching, haunting sense of urgency.

Indeed, one can go movement-by-movement through this recording and point out highlights: the intensity of the choirs’ tone and the responsiveness of the orchestra’s playing in the “Requiem et Kyrie”; the spare desolation of the “Quid sum miser,” which provides such a brilliant contrast to the sonic excesses of the “Dies irae”; the collective ensemble’s demoniac energy in the “Lacrymosa”; the alternation of rich choral singing and superbly balanced flute-quartet/trombone interjections in the “Hostias”; the cathartic sense of return over the last half of the “Agnus Dei.”

That last is one of this recording’s finest features: in live performance and on disc, it’s rare to encounter a reading of this piece that’s as cohesive as Nelson’s. There’s lots of spectacle and effect here, yes, but devotion as well — the conductor draws that aspect of Berlioz’s writing out with marvelous intensity.

But I’m saving the best for last. That would be Michael Spyres’s exquisite account of the tenor solos in the “Sanctus.” This is a punishing part, but Spyres sings it with such serenity, fervency of expression, and clarity of tone – never forced or pushed – that it’s simply breathtaking. Add to that, radiant accounts of the movement’s fugues and a shimmering realization of the soft violin “halo” in the last “Hosanna” section, and this is a benchmark Berlioz Requiem.

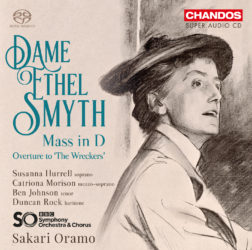

The rehabilitation of Dame Ethel Smyth’s substantial output continues apace with the gripping debut recording of her Mass in D, courtesy of the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus led by Sakari Oramo.

The rehabilitation of Dame Ethel Smyth’s substantial output continues apace with the gripping debut recording of her Mass in D, courtesy of the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus led by Sakari Oramo.

It’s a substantial piece, clocking in at over an hour in length and, if Smyth’s writing here is more extroverted and concertante in character than pious, well, it’s not the only Mass so constructed. Indeed, there’s plenty of urgency and drama to be found in its pages: from the dark, chromatic opening of the “Kyrie” to the murky, unsettled textures of the “Crucifixus” and the furiously turbulent writing in the “Miserere” interjections of the “Agnus Dei.”

There are, too, subtle reminiscences of other composers in some of the pages: Brahms and Parry in the “Kyrie,” Beethoven in the “Gloria,” Haydn in the “Credo.” But, by and large, Smyth didn’t suffer from any anxiety of influence in this Mass.

The score’s striking moments – the combination of string harmonics and oboe melody weaving around an alto solo in the “Gloria’s” “Cum Sancto Spiritu”; the floating soprano solos in the “Et incarnatus est”; the grandiose climax of the “Sanctus’s” “Hosanna in excelsis” fading out to another alto solo – are highly original and ear-catching. And its cumulative effect is, frankly, thrilling: this is a piece that deserves to be heard and sung widely.

Oramo and his forces play (and sing) it with missionary zeal. The chorus’s sound is mighty and robust when called for, gamely athletic in the Mass’s several contrapuntal sections, and sweetly delicate in the music’s introspective moments (like the mellifluous “Benedictus”).

Soprano Susana Hurrell and alto Catriona Morison are the standout soloists, singing with rich clarity throughout. Ben Johnson’s tenor solos in the “Agnus Dei” are likewise compelling.

A swashbuckling reading of the overture to Smyth’s opera The Wreckers makes for an odd filler (or maybe it just emphasizes the theatrical qualities of the Mass). But it’s tautly played and beautifully recorded, all the same.

In all, then, this is a terrific, important release that celebrates one of the most interesting – and hitherto overlooked – composers of the late-19th and early-20th centuries in style. Don’t miss it.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Chandon, CPO, Dame Ethel Smyth, Grand messe des morts