Opera Album Review: A Renaissance-Toned Opera by Saint-Saëns, Finally (and Finely) Recorded

By Ralph P. Locke

Proserpine, one of Saint-Saëns’s most praised and most frequently performed operas, slipped from view after 1919. It can now be heard, in a vivid concert performance by a superb cast and conductor, which won “Best Opera” from the International Classical Music Awards.

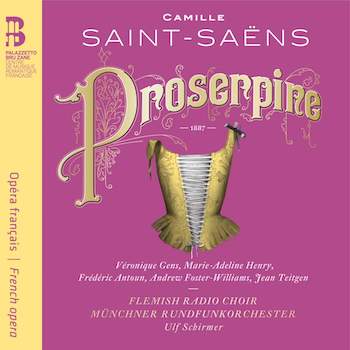

Saint-Saëns: Proserpine

Véronique Gens (Proserpine), Marie-Adeline Henry (Angiola), Frederic Antoun (Sabatino), Andrew Foster-Williams (Squarocca), Jean Teitgen (Renzo), Mathias Vidal (Orlando), Philippe Nicolas Martin (Ercole), Artavazd Sargsyan (Filippo, Gil), Munich Radio Orchestra, Flemish Radio Choir, conducted by Ulf Schirmer. Ediciones Singulares 27 [2CD] 95 minutes

Saint-Saëns is best known, indeed widely loved, as a composer of orchestral works, such as the Symphony No. 3 (“Organ”) and Carnival of the Animals. But he was also a prolific and important composer of piano music, songs, sacred music, and—quite centrally—operas of various kinds, from light one-acts to full-length tragedies.

One of his most important operas, Proserpine, has recently been given its world-premiere recording, and the result is a revelation.

Proserpine was first performed in 1887 and then in a revised version (1899). In one version or the other, the work made the rounds of opera houses in many European lands (plus the famous theater in Cairo, for which Verdi composed Aida). But after about 30 years, it disappeared from the boards and remained largely unknown for nearly a century. Saint-Saëns and others thought Proserpine one of his most successful stage works, on a level with his Samson et Dalila. This wonderful recording delights from beginning to end, revealing a fascinating work that uses the technique of recurring orchestral motives, often associated mainly with Wagner, to very un-Wagnerian ends.

The recording (made during concert performances in Munich, bits of which can be seen online) is the latest in a series devoted to forgotten French operas sponsored by the Center for French Romantic Music at the Palazzetto Bru Zane (Venice) on the Ediciones Singulares and Bru Zane labels. The series, notable for its first-rate performances and equally high standards in the smallish book that accompanies each recording, now extends to more than twenty operas, including another important work by Saint-Saëns, Les Barbares; Félicien David’s only grand opera; Herculanum; Halévy’s La Reine de Chypre; Lalo and Coquard’s La Jacquerie; Spontini’s Olimpie; and Mehul’s Uthal.

Proserpine is in four concise acts, each with a somewhat different constellation of singing characters and its own dramatic and musical tone. I find it utterly captivating, not least for its numerous echoes of what we today call “early music.” Saint-Saëns often interacted with Baroque and even some Renaissance music: examples include the oft-performed Septet, which contains a minuet and a gavotte; the opening of the Second Piano Concerto, which sounds like a passage from a Bach keyboard fantasia; the minuet-like middle movement of the First Cello Concerto; and some of his songs with Renaissance texts.

Here he applies this love of old styles to a plot about a Renaissance courtesan. Her name, Proserpine, derives from the Greek mythological figure Persephone, the maiden whom Hades—god of the underworld—seized and brought down to his abode. Two previous French operas likewise entitled Proserpine, by Lully and by Paisiello, deal with that legend.

The libretto derives from a play by Auguste Vacquerie written in 1838. The librettist Louis Gallet toned down some of the events and language to suit the expectations of opera-house audiences, and he and Saint-Saëns made further changes and additions (including a welcome soliloquy for the title character in Act 3) in the second version (1899) recorded here. The composer also took the opportunity to reshape Proserpine’s vocal line so it could be more effectively sung by a normal soprano. (The original version was written for a dark-toned mezzo.)

The characters are vivid, contrasting sharply with each other. Their interactions derive naturally from what we learn about them. And Saint-Saëns gives them marvelously inventive and attractive music, including some sections that feel almost like set pieces, such as scenes in Act 1 underlined by a sicilienne and an off-stage pavane. For the 1899 version Saint-Saëns added at the opening of Act 2 a lovely “Ave Maria” for the nuns in the convent where the virtuous Angiola has taken refuge.

The libretto often recalls, with interesting twists, elements in well-known operas. Act 1 introduces us to a room full of male courtiers who gossip and tease, much as in the opening of Rigoletto. The role of Sabatino (tenor) feels sometimes like a mix of the Duke of Mantua from Rigoletto and Alfredo from La traviata—except that Sabatino never gets to sing coloratura. (Florid singing is rare in operas written at the end of the 19th century, especially in male roles.) Angiola, whom Sabatino loves, is achingly innocent, as if the sister of Alfredo—whom we never actually meet in La traviata and whom her father Germont calls “pure as an angel”—has here finally snagged a role.

Soprano Véronique Gens, who takes the title role in this recording of “Proserpine.” Photo: Marc Ribes.

Most fascinating of all is the title character. Proserpine is—like Violetta in La traviata—a teasing courtesan, in love with a man who rejects her (Sabatino). The role, even with Saint-Saëns’s belated adjustments to the vocal line, demands a singer with a wide range from deep lows to gleaming highs and displays a wide range of emotions, from playful to desperate to vicious. Proserpine even gets a bit of coloratura at moments of manic joy (at the end of Act 1 when she invites everyone to an orgy). The Act 3 soliloquy, “Pourquoi suis-je venue,” where Proserpine powerfully invokes her mythological namesake, could easily become one of those beloved excerpts that sopranos put into recitals of French arias. Less easily separated from its context is the highly dramatic duet for the two women later in Act 3, where Proserpine, disguised as a fortune-telling Gypsy, tries to sow doubt in Angiola’s mind about Sabatino and then, revealing herself, threatens the innocent—but, as becomes clear, hardly naive—Angiola more directly.

There are several other interesting plot complications and, toward the end, sudden violence. Exactly how the Angiola-Sabatino-Proserpine love triangle should be resolved varies in the two versions of the opera. In the version recorded here (which I think works quite well), Sabatino prevents Proserpine from stabbing Angiola, and Proserpine—realizing the hopelessness of her situation—then stabs herself and, wishing the couple well, dies. Two other characters are particularly well drawn: Angiola’s brother Renzo, and the thief and intriguer Squarocca.

The orchestra greatly reinforces the shifts in dramatic atmosphere and contributes music that is shapely and gratifying in itself (as in the prelude to Act 1). The score’s musicodramatic principles are often not far from Wagner (as Saint-Saëns happily admitted), but the music is much less chromatic (except at certain moments of high dramatic intensity), and the melodic lines often fall into easily digestible four-bar phrases. The frequent touches of earlier styles add to the enjoyment and variety, as do standard operatic devices, such as Squarocca’s drinking song in Act 3 or, in the Act 2 finale, an extended climactic passage where the characters sing their feelings over repeated surging phrases in the orchestra—a passage that reminded me of Donizetti (e.g., the sextet from Lucia di Lammermoor) and Verdi. This finale was so well appreciated at the 1887 premiere performance that it had to be repeated. The opera’s orchestral writing—by one of France’s great writers of symphonies and symphonic poems—is brilliantly accomplished and appropriately varied.

Cast taking a bow after a live performance of “Proserpine” in Munich’s Prinzregenten Theater. Photo: Photo: DR / Munich Radio Orchestra.

This mixture of Wagnerian and more traditional operatic procedures confused the critics of the day, but today seems utterly sensible and not that different from Massenet or Puccini. Proserpine is an opera that deserves to be staged: it may well be one of the strongest French operas of its day, and it blossoms under the hands of first-rate performers.

The reading here could hardly be bettered. It helps that the cast members are mostly native French-speakers. All but one of the vocal soloists sing with beautiful, steady voices. Véronique Gens is as consistently admirable and as admirably consistent as she was in Herculanum and La Jacquerie. Her rounded, soft-edged soprano contrasts nicely with the brighter sound of the soprano singing Angiola, Marie-Adeline Henry. Frederic Antoun conveys Sabatino’s self-centeredness without forcing the voice into edginess. Bass Jean Teitgen presents Renzo’s motives with careful ambiguity. (Renzo sets the plot in motion by requiring Sabatino to offer love to Proserpine as a kind of “test” before Renzo will allow him to marry his sister Angiola.) Only the Squarocca, bass-baritone Andrew Foster-Williams, shows some roughness in vocal production (a wide vibrato and ungainliness with small notes), but it suits the character’s villainy. Foster-Williams also lacks strength in the lowest notes of the part. The minor roles are marvelously done: Mathias Vidal is a treasure!

The Munich orchestra plays splendidly under its chief conductor. The excellent sonics are helped greatly, I suspect, by the intimate acoustics of that city’s Prinzregententheater (1122 seats).

The book that comes with the recording contains informative and perceptive essays, including one by the composer and a trenchant musicodramatic analysis by Hugh Macdonald, a fuller version of which can be found in his recent masterfully researched and engagingly written book Saint-Saëns and the Stage: Operas, Plays, Pageants, a Ballet and a Film (astonishingly, the first book ever written about that composer’s copious output for stage or—late in life—screen). The French essays are translated into mostly clear, sometimes too literal English. The libretto—in French and English—is intriguing in itself (despite two pronoun errors in the translation).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Tagged: Ediciones Singulares, Flemish Radio Choir, Munich Radio Orchestra, Proserpine, Ralph P. Locke, Saint-Saëns

I am always glad to see another article by Ralph Locke in the Arts Fuse. I was especially interested in what he had to say about the baroque elements in the opera. I wouldn’t have expected that from this composer and hadn’t realized how often baroque elements appear in some of his other works.

Thanks for the appreciative words! I like trying to connect a work that I’m reviewing to some others that readers might already know–or might want to get to know.

–As an example of pseudo-Baroque style in Saint-Saëns’s instrumental works, here’s the Menuet (Minuet) from his Septet (for an unusual chamber ensemble including a trumpet): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qR-LRkqBDw

–Or the very Bachian opening of his Piano Concerto no. 2:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JU_38vHzmyo