Book Review: “Interior” — The Thing-as-Himself

Thomas Clerc’s novel reminds us of a stubborn truth: we are all narcissists that live to accumulate shit in rooms.

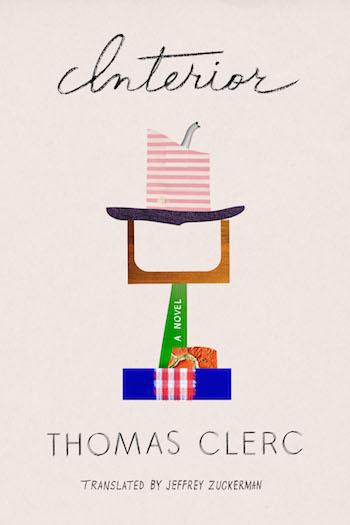

Interior by Thomas Clerc. Translated from the French by Jeffery Zuckerman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 352 pages, $27.

By Lucas Spiro

Thomas Clerc’s novel Interior is a description of an immense collection of commodities, a meticulously detailed catalogue of the objects in the writer’s apartment in Paris’s 10th arrondissement. He presents this inspection as a form of revelation: exposing himself to himself and to the reader through his scrutiny of consumer objects. But he ends up closing himself off from the world, driving himself further into interiority and alienation.

Paradoxically, that is because the world constantly intrudes on his “sanctuary.” All of the objects in his home come from somewhere else and his doorbell mysteriously rings over and over again — only he finds no one there.

Interior is an experimental novel that sets out to examine our attenuated connections with other people through a a man’s relationship with the material objects in his life. Originally published in 2013, Jeffrey Zuckerman’s translation of Interior introduces Thomas Clerc to English speaking audiences. No doubt some will toss Clerc’s book aside, finding it a droll but essentially masturbatory exercise of a bougie Frenchman, not nearly #resisty enough. What good can it do to put where you live, the things you own, under the microscope? This novel reflects our consumerist obsession — it offers no obvious critique. None, really. But that’s ok. Clerc sees fiction as an exercise in elemental artistic expression — the relationship between form and content, something I’d like to believe still carries some real life implications.

Clerc, both the fictional version and the real one, is an academic, writer, performance artist, and does the “thankless” job of criticism. His previous literary projects include a novel where he walks around every street in the 10th arrondissement — the exterior to his interior. But he is a self-professed homebody, eager to document his “desire to remain hermetically sealed from the outside.” Clerc’s novel reminds us of a stubborn truth: we are all narcissists that accumulate shit in rooms. What do we really do? How do we actually live? Clerc’s fictional representation of himself is meticulously realistic in that he discloses an endearing, unapologetic affection for the things he has. Even the things he dislikes he often keeps for the same irrational or contradictory reasons we probably all share. (Do I really need those volcanic rocks, ironic finger puppets, or a collection of Ronald and Nancy Reagan’s love letters? Probably not, but I can’t see why I’d toss them to the curb, either.) “We might think about it the way Stalin did,” Clerc concludes while musing over his footwear habits, “it may be shit, but it’s our shit. How odd that a communist gave us the best definition of property.”

The structure of Interior follows the blueprint of Clerc’s one-bedroom apartment. In these 352 pages we are given intimate descriptions of his entryway, bathroom, toilet, living room, office, and bedroom. It is an exercise in tedium, a detailed account of postmodern life through the things he possesses. He touches on many themes that define today’s moment: isolation, alienation, and obsessive behavior. He promises to reveal secrets, but he remains somewhat cagey. He fetishizes the possibilities of a purely superficial evaluation, all conveyed through vignettes, which evades us ever truly learning who Clerc is — which is part of the point. Then again, perhaps the ego lurks just below the surface. Our rich inner lives are often just as mysterious to ourselves as they are to those around us.

Interior is filled with the elisions, the multivalence, and the Derridean and Nabokovian slippage of language that one expects from an overtly self-conscious postmodern French writer whose influences are laid bare on the page — George Perec and Oulipo restrictions, conceptual art, Roland Barthes and Le Corbusier. It is a novel of (and about) limitations, imposing rules and breaking them, objects as a language and how objects represent our culture, how space determines the ways we live. He even asks a more fundamental question; can life be art?, or just how performative is life? Clerc is a Barthes scholar and invites critiques along Barthian lines. In a recent piece on Barthes in the Times Literary Supplement, Andy Stafford writes: “as actants in different cultures, we accept the social and cultural meanings ascribed to objects merely as an agreed convention, as signs that allow a society to function. To show how society operates, we must ascertain how meanings are produced, circulated, consumed and (to some extent) interiorized: which, in short, is the function of ideology.” In other words, no matter how far Clerc retreats into domesticity, he inevitably runs into the Other.

Some may find Clerc’s overall project more an act of pretentious navel gazing than ideological analysis. Other readers may be more forgiving, given the irony, humor, and self-awareness of the writer’s prose. Clerc is willing to admit that his book is “omphaloskeptic.” All he is “really doing,” he confesses “is simply trying to bury the era during which, deep in debt and unable to live the materialist life, I couldn’t even give myself (any) credit.”

That Clerc so often renders his subject in economic terms, unflinchingly referring to himself as a member of the bourgeoisie and having no class illusions whatsoever (this is a default attitude in French society) suggests that readers looking for “academic” critical fodder will find plenty in Interior‘s useless round-up of stuff. Clerc is obsessed with the relationship between form and content, of function, of what the things that literally do nothing say about the way things are done in the world. The novel look at psychological desire is a commentary on an era of reality television, of virtual reality, of the breakdown between artifice and art, of how life is mediated by performance. People spend their lives trying to accumulate objects — but they are never the objects that they really want. People desire what the object represents, what it “says.” When Clerc finally arrives at his bedroom and describes the garments in his wardrobe, he says “I’d rather define myself with costumes, disguises, and false outfits than strip down to my bare skin.” So much for secrets — and for the bare truth.

In Barthes’s influential Mythologies, an essay collection where he “interprets” everything from dish detergent to the Citroën DS, he says that he has “tried to define things, not words.” Clerc also attempts to define a thing, the thing-as-himself, only to find this particular object’s meaning more elusive than he expected. In fact, the author preempts the act of going beyond the surface. Interior exposes the limits of verisimilitude, the dead end factuality of cataloguing. Clerc’s project is as tragic as it is absurd, in that it suggests the impossibility of representing the totality of things, even when they confined to a one-bedroom flat. “I always seem to shy away from the sheer scale of my project by avoiding this or that particular aspect,” he admits, and concludes “it would appear this voyage into the heart of my apartment is more than my meager talents can manage.”

At the end of Interior, Clerc has the rest of his apartment to describe. And he has the momentous burden of addressing the other nineteen Parsian neighborhoods he left out of his other novel. On the one hand, we have a worthy addition to the tradition of writers who quarrel with the limitations of their craft, who stretch the form via linguistic trompe l’oeil, reassessing the function and nature of mimesis. But things are limitless and time is limited — so I suggest Clerc look for some short cuts (philosophical and topological) if he wants to advance his avant-garde mission.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.

Tagged: french fiction, Interior, Jeffrey Zuckerman, Lucas Spiro, Thomas Clerc