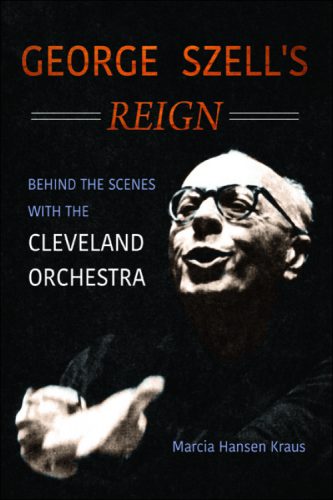

Book Review: George Szell’s Reign — Behind the Scenes with the Cleveland Orchestra

George Szell’s Reign is ultimately an accessible, often sociable, but sometimes perplexing fan’s history of the Orchestra and its storied music director.

George Szell’s Reign: Behind the Scenes with the Cleveland Orchestra by Marcia Hansen Kraus. University of Illinois Press, 272 pages, $34 (hardcover) $30 Ebook.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

It’s an accepted fact that George Szell was one of the 20th century’s leading conductors. A maestro with an impeccable ear, extraordinary technical gifts, a sure command of the standard canon, and a fearsome temper to boot, Szell’s twenty-four years at the helm of the Cleveland Orchestra mark a significant era in post-war classical music, generally, and American orchestral history, particularly. Marcia Hansen Kraus’s book, George Szell’s Reign: Behind the Scenes with the Cleveland Orchestra, offers an accessible, often sociable, but sometimes perplexing, overview of that period.

On the one hand, it provides welcome tidbits of information for those interested in how a significant, mid-20th-century American orchestra operated. There are lots of interviews with musicians who were members of the ensemble at various points during Szell’s tenure. And when the book turns to more personal subjects – a section on Szell at his home, for instance, or the chapter on Robert Shaw’s rapport with the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus – Kraus’s writing is most revealing and engaging (who’d have guessed that Szell was an accomplished cook?).

At the same time, Szell’s Reign is ultimately a fan’s history of the Orchestra and its storied music director and it succumbs to the two primary flaws of such an approach: a narrowness of focus and an unwillingness to ask hard questions or to dig too deeply into the subject at hand.

For instance, Szell’s Reign does nothing to place the conductor in any sort of context. Rather, Szell is presented as something of a fait accompli: a brilliant musician who, single-handedly, rescued the Cleveland Orchestra from the doldrums of mediocrity and, by force of will and personality alone, made it the best orchestra in the land.

Now, granted, Szell was a great conductor who possessed terrific charisma and commanded respect from the podium. And he turned the less-than-great ensemble he inherited in 1946 into one of the 20th century’s finest. But how did he fit into the larger orchestral landscape of the day? Don’t bring that question to this book.

Taking just a superficial look at other Big Five American orchestras and their leadership between 1946 and 1970 shows Rafael Kubelik, Fritz Reiner, Jean Martinon, and George Solti in Chicago; Dimitri Mitropoulos and Leonard Bernstein (among others) leading the New York Philharmonic; Eugene Ormandy helming the Philadelphia Orchestra; and the triumvirate of Serge Koussevitzky, Charles Munch, and Erich Leinsdorf directing the Boston Symphony. Munch in Boston and Reiner in Chicago were, with their orchestras, easily in Szell’s league, and you can make persuasive cases that the other two were, too.

But there’s really no discussion of any of this in Kraus’s book. Quite the contrary: the fact that the twenty-five years after World War 2 were, arguably, the peak of the Golden Age of American orchestras is not explored. Neither is Szell’s place in what was a much larger and richer orchestral scene. Some sense of either of those things could have provided a healthy counter-weight to Kraus’s breathless praise of all things Szell (even as Szell’s Clevelanders were rightly renowned among the Big Five for their technical brilliance and tonal luster).

What’s more frustrating is the general lack of depth the book goes into concerning Szell the musician. Indeed, there’s more technical analysis of the building of the Cleveland Orchestra’s summer home in Blossom, OH (a fascinating topic and well-told by Kraus) than there is insight into Szell’s work as a conductor.

A chapter that purports to focus on his interpretations of Haydn and Schumann, for instance, spends literally one paragraph comprising four sentences discussing one movement of Haydn’s Symphony no. 88. Szell’s recordings of Haydn symphonies, we’re told, “fully manifested Haydn’s genius.” How? Through careful rehearsal, for one. Want more than that? Well, you’ll just have to check out the recordings and figure it out for yourself.

The Schumann section is a bit more substantial (it gets ten paragraphs) and, amid tangents on how Szell marked up his scores with different-colored pencils, we learn that he reorchestrated the symphonies before recording them in the late-‘50s. The finished product, Kraus promises us, has “never been equaled” – though how or why, specifically, that’s the case is left obscure.

It doesn’t help things that Kraus arranged her text sectionally rather than chronologically. That is to say, by the division of the orchestra’s instrumental families (woodwinds, brass, percussion, strings, separated by short chapters on other themes).

In and of itself, this isn’t a bad thing. We get to meet a variety of great musicians from each group as a result. Some – like violinist Joseph Gingold and hornist Myron Bloom – remain legends.

Others, like oboist Marc Lifschey, are idiosyncratic footnotes. Indeed, some of Szell’s Reign’s most amusing anecdotes concern Lifschey, whose recalcitrant personality grated against Szell’s domineering will and whose tenure – which ended abruptly in the middle of one season with a messy, public resignation – only endured as long as it did by dint of the excellence of the oboist’s musicianship.

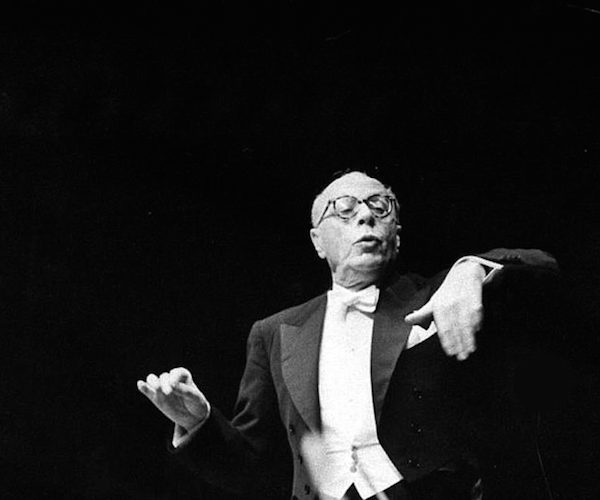

Conductor George Szell in action.

But this layout wreaks havoc on Kraus’s chronicle of the sequential history of Szell’s directorship. There’s lots of jumping around: sometimes to the mid-‘50s, sometimes the mid-‘60s or late-‘50s; occasionally back to the late-‘40s, and transitioning between those periods isn’t one of her strengths. What’s more, there’s little evident reason, once you get to the end of the book, to suggest why this organization of materials had to be the case.

Perhaps the most disappointing element of Szell’s Reign, though, is the title character himself. He remains distant and aloof. Certainly his musicians – most of them, at least – held him in high esteem and Kraus includes plenty of admirable tributes to his musicianship, his moral example, and his affection for the members of his orchestra. But relying almost solely on their views of him all but ensures a certain chilliness between subject and audience.

So Szell remains a cipher, almost always alluded to from a distance: a “great musician,” a “genius,” a man with an impeccable ear. It makes sense that his players would view him as a kind of Olympian figure, especially in that era. But Kraus doesn’t supplement their views by penetrating much deeper in her research. There are interesting tidbits related to Szell’s home life, but precious little concerning his own views on music or his relationship with his players – the very things that would add a welcome dimension to this book. At the end, Szell remains an impenetrable, otherworldly shadow, experienced, yes, but not much known.

Having said all this, the general introduction that George Szell’s Reign gives to the conductor’s life and work is welcome, and the book lays a foundation for further research into the conductor’s career. Not the biggest platform for the latter, mind you, but a solid enough one upon which to expand. The interviews with players and administrators Kraus includes are revealing and the book’s notes suggest there are plenty more nuggets are to be found in information that was ultimately cut from the text.

So, even if it’s too often shallow and skips a bit glibly from subject to subject, nobody gets hurt and, at the end, you may well want to dust off your old Szell records to see if all the book’s references to his and the Cleveland Orchestra’s brilliance over these years are, in fact, accurate. In all likelihood, they are.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Thanks for that informative review. I guess John Culshaw’s autobiography tells us more about Szell the man, well at least his financial acumen.