Rethinking the Repertoire #20 – Vasily Kalinnikov’s Symphony no. 1

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the twentieth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

“Anyone who likes Tchaikovsky – anyone,” conductor David Robertson told NPR in 2013, “is going to adore [the First Symphony by Vasily Kalinnikov].” Sounds good so far. So why haven’t you heard it?

“But I have had to use extremely creative measures to get this symphony performed,” Robertson continued. “And in fact, I have been unsuccessful except where I’ve been music director, because there’s this notion of, ‘Here’s this big unknown symphony by someone whose name sounds like an automatic rifle’.”

Therein lies the rub: great music, but it’s by an obscure composer. Thus, the Boston Symphony hasn’t performed the score since 1937, the New York Philharmonic since a month before Paris fell to the Allies in 1944.

Not that you can blame Kalinnikov for his posthumous fate: he had a rough go of it in his short time on earth. Born in Oryol, Russia in 1866, he died two days before his thirty-fifth birthday in 1901. In that brief window, though, he made a something of a name for himself among Russian musicians of the day. Tchaikovsky recommended him for the directorship of Moscow’s Maly Theater and among his circle of close friends was Sergei Rachmaninoff.

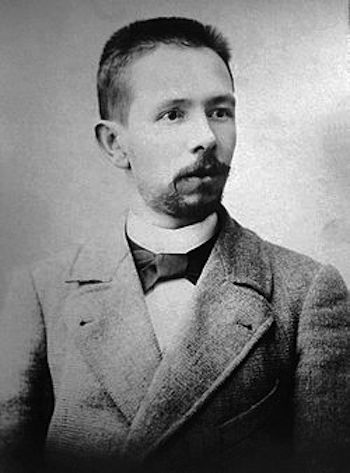

Composer Vasily Kalinnikov — his First Symphony is as fresh as they come.

Often ill over the last decade of his life (he died of tuberculosis at Yalta, where he had settled in the mid-1890s), what’s remarkable about his output isn’t the amount of it – respectable sums of symphonic, keyboard, vocal, and choral works – as much as the sheer, exhilarating energy that marks the best of it. You encounter this last most markedly in Kalinnikov’s two symphonies, but especially the First, which was completed in 1895, premiered in 1897, and, in Russia, at least, seems to have a secure toehold in the repertory. In the West, it’s fate has been another matter, though there’s no good reason for that to be the case.

Kalinnikov’s First Symphony is about as fresh as they come. The first movement doesn’t waste a moment: it kicks off with its sweeping opening theme and never looks back. The second main tune sounds a bit like something lifted from Borodin, but that’s neither here nor there – it’s lush and winning, and that’s all that counts.

In terms of structure, the movement’s development section’s a bit bloated and disjunct – what, exactly, becomes of the fugue that kicks off around the midpoint? – but, again, Kalinnikov’s handling of his materials is so assured that it really doesn’t matter. His way with them is almost improvisatory, as though he’s trying out ideas on the spot, running with the ones that work and dropping the others. And the Technicolor scoring constantly shines: Kalinnikov clearly knew his Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, but his writing for the orchestra never sounds derivative.

That fact is reinforced in the opening bars of the gorgeous second movement, in which a harp-violin ostinato is framed by a series of falling chords whose changing instrumentation causes the music’s tonal colors to shift like light through a prism. After that, a sumptuous, diatonic melody is contrasted by a vaguely Oriental-sounding theme, and the two strike up a tentative, beguiling dance that wanders between the remote keys of E-flat major and G-sharp minor. The whole thing is pure magic: writing of delicate, visionary genius.

The third-movement scherzo, by contrast, is an earthy romp that calls to mind the Slavonic-inspired scherzi of Dvorak and Tchaikovsky. A dolorous trio that admirably showcases the woodwinds provides a moment’s respite before a reprise of the opening section brings the music to a spirited conclusion.

To close the piece, Kalinnikov constructed a finale that’s a tour-de-force of thematic transformations plus new themes derived (or closely related) to the old ones. Each movement is referenced in turn, with the noble first melody of the second movement rounding things out. Before that grand conclusion, though, comes about nine minutes of unbridled joy, surely one of the most exuberant concluding symphonic episodes in the 19th-century symphonic canon.

So where has this music been all its life? Robertson’s quote above speaks to the challenges of sustaining interest in a composer who died young and reputation hasn’t really exceeded the boundaries of his homeland.

True, Kalinnikov’s symphonies, at least, seem to have gained some currency in the West in the decades just after his death. But shifting tastes over those years – first, towards the various -isms that became fashionable in the years after World War 1, then the fiercer battles waged between the avant-garde and everybody else in the years after the Second (not to mention the frantic stylistic splintering that has defined contemporary music for the last half-century now) – played a big part in consigning it and a lot of music like it to the margins or the back shelf.

How to salvage these pieces, then? Well, we’ll get into some of that in the wrap-up for this series, but the gist of it is to advocate for them. And, if you don’t know the music to begin with, how can you make noise on its behalf? Kalinnikov’s First Symphony – especially when heard in as exuberant a performance as the one Evgeny Svetlanov leads of in the links above – is just one of those works well worth beating a drum for.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Evgeni Svetlanov, Russian Classical Music, Symphony no. 1

My four British CD guides don’t even mention him! “Third ear” gives him, and Svetlanov, half a page, and a rave review. Kukar on Naxos has all the symphonies and third ear suggests his “warm embrace is irresistible”. I streamed the first movement of #1 from both and found Svetlanov spirited but a bit rough, and Kukar, indeed, warm and embracing! I’m feeling the need for warmth, so I’ll plump for Kukar for now…

[…] Rethinking the Repertoire #20 – Vasily Kalinnikov’s Symphony no. 1 […]

I discovered the Kalinnikov 1st symphony by sheer chance as I noticed it listed on Youtube while I was listening to Nathan Milstein’s performance of the Glazunov violin concerto, which I love. I am not a musician, have never played an instrument, but have listened to classical music all my life. Since finding the Kalinnikov I have played it repeatedly and think it is glorious. Cannot believe I have never heard of his music before. It should be much better known, but I suspect that it might be too “accessible” for those who consider their ears more sophisticated than the ears of ordinary listeners like me.

I am now about to listen to his second symphony and hope that is as wonderful.

Why doesn’t someone other than myself comment on, fall in love with him for, and otherwise burst into tears of love and pastoral naturalism on every hearing of the major third ostinato of movement 1 of Kalennikov’s first symphony, which has to be a spin-off nostalgia trip from Beethoven’s similar mourning dove motif of Symphony VI??

Heard for the fourth movement of the 1st Symphony for the first time this morning on BBC Radio 3. Now listening to the rest on YouTube. Where has this symphoy been all my life ? Why isn’t it part of the mainstream repertoire?