Theater Commentary: “Skeleton Crew” — Not With the Union

To my surprise, the auto union was written out of the picture from the start, as if dramatist Dominique Morisseau saw it as an embarrassment.

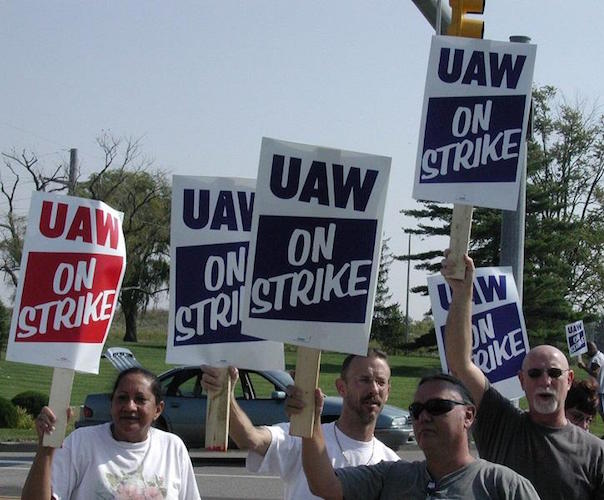

Auto workers protesting. Photo: Steve Carmody/ Michigan Radio.

By Bill Marx

One of the reasons I wanted to see the Huntington Theatre Company production of Skeleton Crew is its promisingly relevant plot, which revolves around black auto workers faced with the closing of their plant in Detroit during the 2008 financial crisis. Surely the employee’s union would play a vital part in the action in some way? And that would be a refreshing reflection of American reality on our stages. In contemporary drama, unions are rarely present, even though their importance, in terms of fighting for living wages and fair treatment for workers, has proven to be indispensable.

Why are unions off-limits? For the same reason corporate boardrooms and the 1% who haunt them are usually left out of the dramatic picture. A fear of looking at the ‘invisible’ levers of power in the real world, a reluctance to invite charges of being didactic, and anxiety about alienating audience members and the moneyed classes (bankers, corporate leaders, lawyers, etc) who fund or support performance events. Both Left and Right unite in welcoming — as far as American theater is concerned (at least given what we see in Boston) — a vision of unions and corporations in which neither are held accountable for what’s happening today. The focus is inevitably on the traumatic effect of financial down times on individuals or families, rather than taking a diagnostic look at the external structures – cultural, political, and religious – that challenge their survival.

So I wasn’t surprised that the decision makers at the top are never seen in Skeleton Crew. They are nameless, faceless, and (assumed to be) white representatives of the way things are and must be. But I figured that the workers would most likely ask their union for help in the face of economic disaster. Believe me, I was not demanding an idyllic portrait — the more fraught the depiction the better, including accusations of union bosses’ complicity with the corporate powers-that-be. But, to my surprise, the union was written out of the picture from the start, as if dramatist Dominique Morisseau saw it as an embarrassment, a problem that needed to pushed aside as quickly as possible.

Here is how she dispenses with it. The veteran union rep in the play, an older woman, has a strong personal relationship with the foreman. (She helped get him his job.) Well before it has been officially announced, the foreman tells her that he knows the plant will be closing. He swears that he will do his best to make the landing for the workers soft. The foreman asks her to be silent in order for him to do that. (The implication is that the union will take unhelpful action once it finds out.) She keeps mum, though, when challenged, she sticks up for the union as well as its history of supporting workers at the plant. There is considerable fuzziness in Morisseau’s central set-up: Is it reasonable that only one foreman would find out about the upcoming closing, which would take place in a year? Wouldn’t someone else tip off the union, given that rumors of the company’s packing its bags are rampant?

For some critics, the union rep is making a moral decision. Choosing trust of an individual over distrust of an organization. (The move subtly puts the union and the corporate honchos on the same footing.) For me, keeping the closing secret is a dereliction of duty: her decision to keep quiet wastes precious time – opportunities for protests and law suits, marches, political lobbying, and publicity campaigns. But that would have been another play, the kind that we hardly ever see, even though these days have been rife with unions (teachers, food workers) raising a ruckus.

We are never even told when the union finds out about the plant closing and what it chooses to do once it learns the news. Why not? (Did the foreman negotiate a better deal for the workers all by his lonesome?) Skeleton Crew became a regional theater favorite because it provides the standard up-with-people response to economic difficulties: when the going gets tough, superior people come together, domestically. Community never means employees organizing to fight back via a protest; it is used as a way to serve up middlebrow celebrations of love and the merits of nurturing. Nothing in society need change – or is even challenged to change – because the afflicted families will bond together and make things work out. (Of course, the crisis of 2008 destroyed legions of families and neighborhoods.) I would also argue Morisseau made the safe choice of family togetherness because the workers would have lost the sympathy of audience members had the union been asked to play a pivotal role. Workers have to be seen as passive rather than active if they are to maintain the sympathy of theater audiences. Then they can be categorized as plucky victims who make the best of a bad situation that none of us dare combat or mitigate. (Do not slap away that open invisible hand!)

The truth is, talk of a strike discomforts theater audiences; scenes of bonding are so much more reassuring and heart-warming. I have not seen Stephen Karam’s The Humans, which is currently running at the Boch Center, but it too, at least judging by the reviews I’ve read, is another example (like Skeleton Crew) of the “pressure cooker play” genre: helpless characters (often downwardly mobile or painfully afflicted) find themselves trapped, caught in a hopeless situation that presses them to the limits. Who maintains their humanity? Who fails? Of course, audience members aren’t being tested, just eying others (with a fig leaf of empathy) as they jump through hoops. (The granddaddy of the pressure cooker is Sartre’s No Exit – the heat in Hell is set on eternal high.) The idea of turning off the cooker is never raised in these scripts because convention is to be respected rather than attacked.

So why is the union tossed aside in Skeleton Crew? Because our playwrights and stage companies won't tackle realities audiences don't want to deal with.Click To TweetSo why is the union tossed aside in Skeleton Crew? Because our playwrights and stage companies won’t tackle realities audiences don’t want deal with: I have already written about our theater’s reluctance to take up climate change. Labor strife is on the list of verboten subjects, along with rampant corruption amid the corporate and political classes. A current greed-fest ripe for satire: Elizabeth Holmes, founder and chief executive of the blood-testing company Theranos, was charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission with an “elaborate, years-long fraud” in which she and former company president Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani allegedly “deceived investors into believing that its key product — a portable blood analyzer — could conduct comprehensive blood tests from finger drops of blood.” Wired magazine amusingly characterized the multi-multi-million dollar scam as a perfect example of Silicon Valley’s ‘Fake it until you Make it Culture.’ (How Ben Jonson would have adored that description of money-making skulduggery.) And then there is the tragedy of the opioid epidemic, which in 2016 killed over 64,000 people in this country. (In 2017, Detroit had more opioid overdose deaths than murders.) Crushing poverty, pervasive family dysfunction, social breakdown, and spiritual emptiness are spreading across the heartland — time for an American version of Gorki’s Lower Depths, a pressure cooker play that bakes addicted humanity to a crisp. But no major theater would dare produce it.Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

For readers or theatre producers interested in a strong, provocative play about unions, you might inquire about Rebecca Gilman’s Soups, Stews, and Casseroles: 1976. It premiered at the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis in 2015, and has since been produced at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago. It’s an excellent play about the beginning of the end of the union movement in the 1970’s.

Thanks so much for the tip. I have not always been a fan of Gilman’s plays, but I will read this play. And hope theater producers will as well.

Thank you for these thoughts, which I shared after seeing the show. On another note, I am directing The Cradle Will Rock and while we don’t have our shows reviewed, I would just love to share the work with you because these students are bringing their A game and we are all feeling beyond inspired by Mark Blitzstein’s spot-on look at both the need for unions and the prostitution of all facets of ‘civilization’ in the capitalist system. Please let Ian know too. its Next weekend only. 4 shows. thanks Bill.