Film Commentary: October — A Month of Horror, Multiplying

I love subtlety, and beauty, and trash, and terror, in equal measure.

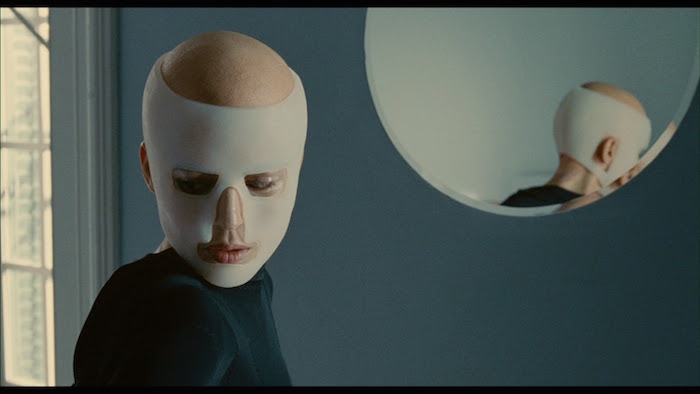

A scene from “Halloween III, Season of the Witch.”

By Peg Aloi

If you’re like me, you look forward to October for a myriad number of reasons, from the natural the aesthetic. The cooler weather, the colorful foliage, the apple picking, the cider donuts, the crisp air, and sensual scents of nature. Also, of course, Hallowe’en.

Hallowe’en is big business now, a runner-up to to Christmas in terms of consumer spending. Parties, decorations, costumes, candy for trick or treaters, the list goes on and on. And, increasingly, theaters are rolling out horror films throughout the month of October. Television networks and streaming services curate an entire month’s worth of scary fare. Following the tourist/visitor strategy of Witch City (Salem, Massachusetts) which calls October “Haunted Happenings,” the media rakes in millions during the month, drawing in more viewers.TCM, Netflix, Hulu and other networks roll out classic and contemporary horror fare, usually starting on October 1st and continuing through the 31st, in some cases culminating in marathons of scary series or franchises (like all the sequels to Halloween—Halloween 3: Season of the Witch is my favorite, by the way, really ahead of its time and underrated).

Why does this trend keep getting bigger every year? Are we becoming more inured to horror? To the point that there is too much of it out there, saturating the media landscape? Are networks just angling for more viewers any way they can get them? Why do we love being scared? What can horror do for us now? Given the terrifying reality of Trump’s America? There are daily headlines about possible nuclear war, vanishing healthcare, unarmed black people being murdered by police, women being harassed and assaulted with impunity, white supremacists marching in the streets, citizens because of poorly-organized relief efforts in the wake of climate disasters, including wildfires literally burning parts of our world to cinders. How can watching horror fiction help us cope with the real life horror of the every day?

It’s been said that Hallowe’en is a holiday that encourages Americans to process their feelings about death and dying (something we, as a culture, are not very good at). The attraction of the various sub-genres underline this truth. Monster movies let us encounter our fears by turning them into grotesque metaphors, and then suggesting that we can vanquish our nightmares. The undead (vampires and zombies) tap into our yearning for immortality and our horror of physical and mental decay. If consuming blood is all it takes to live forever, who among us would not swallow our revulsion and get down to business? Animated corpses are macabre miracles that we can’t wrap our brains around (ha, BRAINS, get it?) but we are fascinated by the idea, wondering if such a fate might await us after death. Occult stories plumb our anxiety about the afterlife, parsing our doubts about religion and the existence of evil. Slasher stories give us a cathartic way to imagine the worst sort of death; we have escaped unscathed by the time the end credits come around. Still, all these horror genres have one thing in common: they force us to confront our mortality, make us ponder the nature of death. Of course, the majority of horror fans are more likely to say they simply enjoy being scared…but what do most of us fear more than anything? Violence? Evil? Oblivion?

The fact is, reality is influencing horror narratives. Certainly the creators of American Horror Story understand this, and the Hallowe’en month episodes of their latest season (entitled “Cult”) include terrifying clowns and a mass shooting, among other horrors. Narrative genres are becoming more complex and hybridized, branching out from standard by-the-numbers slasher and supernatural storylines to encompass dark thriller, urban horror, folk horror, psychological horror, dystopian horror, etc. Horror is becoming more of a reflection of, or commentary on, the times we live in. Fake documentary horror is one of the most fascinating new hybrids: for example, the satisfyingly gory, clever and hilarious What We Do in the Shadows, a faux documentary about vampires in Australia; or Norway’s brilliant, and often terrifying, found footage/fake documentary Trollhunter.

Audiences are generally embracing this trend towards headier, more socially confrontational narratives. One of the surprise movie hits of the year was a satirical social comedy that riffed on horror tropes and race relations, Jordan Peele’s Get Out. It resonated with audiences who recognized what it was making fun of (the filmmaker called it Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner re-imagined as a horror film). It scored big at the box office, had a 99% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and made it clear that horror can be a genre that speaks truth about uncomfortable social ill. Given the concerns about racism at the moment, Peel’s brilliant satire came at the right polemical time. Another, quieter horror film that portrayed race relations — in a subtler and more serious way, It Comes at Night, presented the trials and tribulations of mixed race families dealing with a terrifying epidemic that slowly tears their worlds apart. It’s an apocalyptic story whose themes go beyond the obvious thrills, suggesting the “thing that goes bump in the night” may be fear, lust, anger, or sheer existential dread.

A scene from the unsettling horror film “Goodnight Mommy.”

Sometimes horror that seems too arty for mainstream audiences catches on, like The Babadook, a spooky Australian tale that revolves around a child and his mother. It is a sometimes supernatural but always penetrating psychological film about the fears of children. Goodnight Mommy was less popular (because it was Scandinavian and thus subtitled?) but no less terrifying: twin boys have problems with their mother’s recent decision to undergo plastic surgery and decide she must be an evil imposter. Then we had last year’s The Witch, praised by many critics but widely hated by audiences. The latter are not at fault for their response because distributors marketed it as a scary mainstream horror film and used complimentary quotes from Stephen King to sell it. But the film, set in Colonial America, featured an archaic English dialect and drew on visual imagery from folklore and fairy tales. Mainstream horror fans couldn’t follow what was happening and could not be bothered to stick around for the violent, horrifying final scenes. The Witch was intended for arthouses, but opened in megaplexes, and it bombed at the box office. The Love Witch fared better — perhaps because it was campy and sexy. But some viewers didn’t appreciate its glorious homages to ’70s trash cinema and Technicolor horror — or its subversive feminism.

The truth is that, despite the wave of sophistication, violence and excitement are what attracts a good number of horror fans: stories that depend on psychological suspense and slow building scares are not popular draws, Watching slasher films may be cathartic for some; they can leave visions of brutality behind at the theater. The archetypal images and subconscious mechanisms of a thriller may linger and haunt. Maybe conventional horror fans don’t enjoy being scared so much as they hunger for a sort of bacchanalian experience, a religious ritual that culminates in release and redemption.

It’s when redemption is not forthcoming that a story’s spell is given lasting (insinuating) power. (Of course, unfinished business may merely be a signifier for a sequel to come). Think about that final scene in Martha Marcy May Marlene when Elizabeth Olsen’s Martha, in a car with her sister and brother-in-law, looks back at the car following behind, knowing that it contains members of the cult she just escaped from. The film doesn’t need the mechanical device of high-pitched screeching violins — it is a moment of sheer terror. Or look at the end of Take Shelter, when Michael Shannon and Jessica Chastain (at last) see an enormous storm on the horizon — is it reality? Does it really matter? They nod in understanding and turn to face the test, as unprepared as ever — and that is the point. Both those endings continue to haunt me — even though they are devoid of intense violence and buckets of blood; the monsters they invoke are of the ordinary human variety, the ones that lie dormant inside us until circumstances awaken them.

Angela Bassett Jessica Lange and Kathy Bates in “American Horror Story: Coven.”

Horror seems to demand immersion; binge watching becomes a national pastime. Though studies show that this this kind of exposure is bad for us — it is not the way to appreciate quality story-telling — we persist in wanting to be overwhelmed. And the networks know it. Some new cable series horrify and frighten in creative ways, from the gory but funny The Santa Clarita Diet, which stars Drew Barrymore as a woman who suddenly develops a taste for human flesh, to Stranger Things (its second season on its way) the Emmy-studded love song to ’80s culture set in a Midwest town in the grip of some ghoulish government experiments on children. It combines horror and paranormal thriller tropes to perfection and the writing, direction and performances are absolutely first rate. Of course you’ve already watched Twin Peaks: The Return, but if you have not, it provides some of the most terrifying (and weird) television you’re ever likely to see. If you can survive Episode 8, you’re prepared for anything. Past series to binge on this month — if you’re caught up on everything else — include Lost, J. J. Abrams’ ambitious story of a mysterious plane crash and its dogged, doomed survivors. Then there’s Salem, the trashy, supernatural-tinged series about witchcraft and witch-hunters; Dexter, the intense, intelligent series about a serial killer who fancies himself a do-gooder; and American Horror Story, the anthology series that, while sometimes uneven, is always stylish and gruesome. Or how about True Blood, a sexy, arty HBO series from director Alan Ball (Six Feet Under) which deals with Louisiana vampires and the humans and other creatures in their midst.

Television marathon showings of classic horror are a delicious treat this time of year (and much less fattening than mini candy bars). Many horror classics not available on cable or the backlist of your favorite streaming channel can be found (in their entirety) on YouTube. Recently a friend sent me a link to Theatre of Blood, a delightfully campy yet horrifying film from the 1970 starring Vincent Price as a disgruntled Shakespearean actor who sets out to murder critics of his performances in imaginative theatrical ways, all inspired by deaths in the plays of the Bard. Other ’70s era films I will seek out this month, partly because I have not seen them in years: Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, Haunts of the Very Rich, Stranger in Our House, The Initiation of Sarah, and Satan’s School for Girls (yes, that one is as awesomely bad as it sounds, a sort of rip-off of Suspiria starring Kate Jackson of Charlie’s Angels). Some of these were made for TV, back in the day when weeknights offered original film fare, stories that clocked in at two hours with commercials. That some of these movies, which I saw last when I was a teenager decades ago, still haunt me tells me that they are very scary movies indeed. Or that my tastes in horror have not really evolved all that much over the years, despite my deepening appreciation that horror is becoming increasingly complicated, political, and challenging. Despite the genre changes, horror still feeds on our hunger for the primal and the mystical. I love subtlety, and beauty, and trash, and terror, in equal measure.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for The Boston Phoenix. She taught film and TV studies for ten years at Emerson College, and currently teaches at SUNY New Paltz. Her reviews also appear regularly online for The Orlando Weekly and Diabolique. Her long-running media blog “The Witching Hour” has recently been moved to a new domain: themediawitch.com.

Tagged: Halloween, Halloween 3: Season of the Witch, horror, horror films