Classical CD Reviews: Sit Fast plays John Dowland and Jurowski conducts Strauss and Mahler

Sit Fast’s performances are breathtaking for their clarity and emotional involvement; Vladimir Jurowski serves up a ho-hum, un-monumental an interpretation of a late-Romantic pillar.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Before the Beatles, before Duke Ellington – before Beethoven and Bach – there was John Dowland. If any composer has claim to a body of perfectly-formed, inevitable-sounding gems, it’s this 15th century English musician.

The seven pavans from his 1604 Lachrimae that form the first half of the viol consort Sit Fast’s new disc for Evidence Classics not only reveal his impeccable sense of musical structure and invention but, more importantly, prove that hi expressive depths remain potent as ever.

Part of a larger cycle of twenty-one polyphonic pieces for viol consort, these Lachrimae movements are a series of studies in melancholy that follow a progression from “old tears” (Lachrimae Antiquae) to “sighing” ones, “sad” ones, and, ultimately “true tears” (the closing Lachrimae Verae). Forms and tempos are virtually identical across the seven, and they share some primary source material (Dowland’s song, “Flow, My Tears”).

Yet there’s scarcely the feel of redundancy between them. Part of that owes to Dowland’s harmonic techniques: like Purcell a century later, he had a keen sense of where and when to use dissonance to the most dramatic effect. He also had a solid grasp of how music functions on a psychological level and the progression from the depths of despair in the first pavan to (a faintly glimmering) light in the last is subtly, but powerfully, evoked.

All of that comes across in Sit Fast’s performances here, which are breathtaking for their clarity and emotional involvement. Never overdone or exaggerated, theirs is a cogent and (these days, especially) necessary demonstration of the powers of a direct, honest argument: persuasive, implacable, and abiding.

George Benjamin’s haunting Upon Silence, a 1990 setting of W. B. Yeats’ “The Long-Legged Fly” for mezzo and viols, proves an ideal outlet for the pent-up emotionalism of the Dowland. Lean, intricately contrapuntal, bracing, it’s music of intense drive and focus. Sit Fast, mezzo Sarah Breton, and lutenist Karl Nylhin turn in a gripping performance, rhythmically precise and expressively vital.

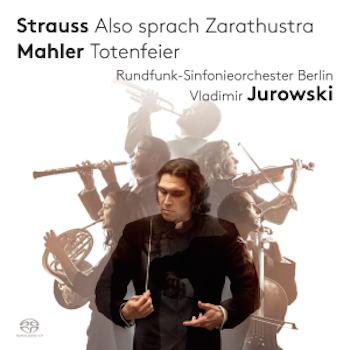

If, for whatever reason, you’ve wondered what a passionless, emotionally uninvolved performance of Also sprach Zarathustra sounds like, look no further than Vladimir Jurowski’s new reading of the Richard Strauss classic for Pentatone. Here’s about as straightforward, ho-hum, un-monumental an interpretation of this late-Romantic pillar as they come.

This is unfortunate, especially given that the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin (RSOB) plays the whole piece with assurance. Textures are remarkably clear and the music’s inventive scoring shines. At the best moments, like “Von dem Freuden- und Leidenschaften” and “Von der Wissenschaft,” the RSOB performs at the technical level of Karajan’s Berliners forty-or-so years ago. But, in terms of emotional power, they’re not consistently on the same plane.

Transitions and interludes are often uneven. Sometimes whole stretches of florid passagework – the middle part of “Der Genessene” stands out – simply mark time, lacking shape and direction. The famous opening fanfare possesses no mystery or magic and “Von der Hinterweltern,” one of the most beautiful moments in all of Strauss, lacks heart.

Some lively moments near the end excepted, “Das Tanzlied” is mannered and the beginning of “Das Nachwandlerlied” needs more power. Oddly, for all the subtleties of the score’s tempo shifts that Jurowski observes in earlier sections, he all but ignores the “noch langsamer” markings over the last page or two. Thus the last bars pack the same antiseptic weight (which is to say featherweight) of the opening ones.

More impressive is Jurowski’s performance of Mahler’s Totenfeier, the 1888 tone poem that later became the first movement of the Resurrection Symphony. The differences between this score and the later symphonic movement largely have to do with scoring, though Mahler made a few cuts around the middle and altered some modulations. But if you know Mahler 2, most of the material here will sound familiar.

The RSOB is certainly at home in its style, playing with rhythmic panache, tonal luster, and a certain youthful (if rather morbid) exuberance. Jurowski teases out the music’s atmospheric gestures in a brisk, rather unsentimental reading that manages to be somber but not unnecessarily weighty.

Alas, it’s hard to get around the ponderous aura of the short Symphonic Prelude that fills out the album. Originally attributed to Mahler but probably by Bruckner, it’s a thickly scored, saturnine essay whose obscurity is probably deserved. Jurowski and the RSOB play it well enough – strings and brass are wonderfully vigorous near the end – but it’s no lost masterpiece, regardless of authorship.

Suffice it to say, neither Totenfeier or the Prelude redeem the unevenness of Zarathustra, which is by far the best composition on the disc. A pity, that, but what’s to be done?

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Evidence Classics, John Dowland, Pentatone, Sit Fast