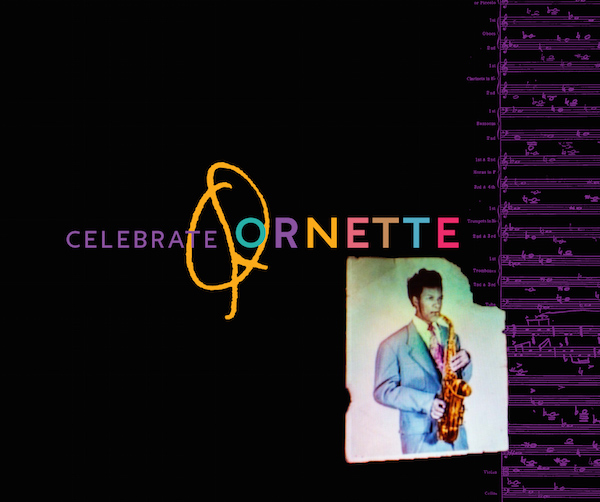

CD/DVD Review: “Celebrate Ornette” — An Exuberant Homage to a Jazz Genius

This indispensable collection demonstrates that the music of Ornette Coleman is in tune with something elemental and essential in the human spirit.

Celebrate Ornette Song X Records: 3 CDs; 2 DVDs, $100.

By Michael Ullman

Even in the world of musicians, Ornette Coleman’s life story is among the most inspiring, and perhaps unlikely. Born in Houston in 1930, he listened to R & B and Bebop as a teenager, and coveted a shiny alto saxophone. Once he got the instrument, Coleman played in blues bands during the immediate post-war years; this was a time when a wailing saxophonist could make hit records, as Hal Singer did with “Cornbread.” At some point, Coleman started hearing different possibilities in his head: perhaps the tension generated between the restrictions of the blues form and the extravagant sounds — the honks and squeals he heard and made in rhythm and blues bands — gave him his innovative ideas. Famously, one night he played the sounds he was hearing and was challenged after the set by some very serious music critics. Eventually, he found his way to Los Angeles, where stalwart beboppers like Dexter Gordon would walk off the stage when he showed up at a jam session.

But Coleman persisted, gathering around him a small group of understanding musicians, some of whom, like Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell, and Billy Higgins, would remain with him for decades. His music became what we called ‘free’: he would play a jagged, broken bottle melody, often made up of two parts, one quiescent, the other an odd rush, and then improvise on whatever part of the tune appealed to him. He’d ignore bar lines and create his own chorus structures. Remarkably, his superb players — and his personnel remained remarkably consistent throughout his career — knew what he was doing and how to follow him. Soft-spoken and iron-willed, he seemed to split the jazz world in two when he debuted in New York City in 1959.

To this listener, Coleman’s allegedly ‘way out’ music was paradoxical: I remember picking up his early album for Atlantic, This Is Our Music, its cover photograph adorned with four musicians glowering uncompromisingly at the camera. They are serious, I thought. But then the music seemed to skip along in its own cheerfully lyrical grooves; missing was the incessant forward drive or intensity of Coltrane, or any other reference to the accepted avant-garde at the time. Ed Blackwell bounced along colorfully on his tom-toms, bassist Charlie Haden played big-toned scales that seemed both elemental and prophetic and, his cheeks bulging, Don Cherry played folksy melodies on a pocket trumpet. To me, it was all somehow welcoming rather than forbidding.

Gradually, Coleman’s music won greater acceptance as it underwent a transformation. Famously he started an electric double quartet called Prime Time in 1988, whose group improvisations could seem either chaotic or finely tuned. (I sometimes believed it had something to do with the places they were playing and how well they could hear each other.) This free improviser wrote a symphony and a string quartet and started amassing awards. In 1994, he received the MacArthur “genius” grant, and three years later was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His Sound Grammar won a Pulitzer Prize. His last years were full of honors and honorariums. He died of a heart attack on June 11, 2015.

A year earlier, his son, drummer Denardo Coleman, decided to put together a musical celebration for his ailing dad. The venue was Brooklyn’s Prospect Park; Denardo’s band was at the center of the festivities, but the gathering included ambitious contributions from a number of giants of new music, including Henry Threadgill, David Murray, Joe Lovano, Geri Allen, and Ravi Coltrane. Patti Smith chanted poetry. Coleman himself performed — in a wavering tone — an absolutely marvelous blues, a triumph of soul over failing technique. It is this concert that is at the heart of the elaborate package Celebrate Ornette recently released by Denardo and Song X. (There’s an even more extensive package available with LP versions of the music.)

All of the tunes played at the Brooklyn concert, as well as the performances at Coleman’s memorial service, can be found on the CDs. The set’s DVDs document both events: the video of the concert includes a welcoming speech by Sonny Rollins, interspersing performances with interviews. The memorial DVD proffers reflections from a variety of people including (of course) Denardo, as well as a generous amount of music: there’s a duet between Henry Threadgill and Jason Moran, a solo by Cecil Taylor, at the beginning of which he chants poetry and, to my ears, sometimes speaks in tongues.

Celebrating Ornette offers much more than nostalgia. There are some unique pairings of musicians: Bruce Hornsby’s duet with Branford Marsalis, Jack DeJohnette with tap dancer Savion Glover, Henry Threadgill on the cumbersome bass flute accompanied by Jason Moran. Nels Cline plays Coleman’s “Sadness” and Threadgill provides a stirring version of Coleman’s blues tune “Turnaround.” It’s a tremendous joy to hear so many Coleman compositions — “Broadway Blues,” “The Sphinx,” and”Lonely Woman” — revived so lovingly and made to dance in a new way. The package comes with an extended booklet full of reflections by Denardo and Ornette’s producer John Snyder. There are photos as well, including a marvelous glimpse, shot backstage, of Ornette cutting up with Sonny Rollins.

Besides its fine performances, Celebrating Ornette proves just how successful Coleman has been and will be in invigorating and challenging generations of musicians. One of the things Coleman told me still resounds in my head: “You can never really be out of tune.” “You’re always in tune with something.” This indispensable collection demonstrates that the music of Ornette Coleman is in tune with something elemental and essential in the human spirit.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.