CD Review: Leonard Cohen — Embracing the Darkness

At 82, Leonard Cohen seems to feel that there isn’t a lot of time left and that he has nothing to prove to anyone, least of all himself.

By Matt Hanson

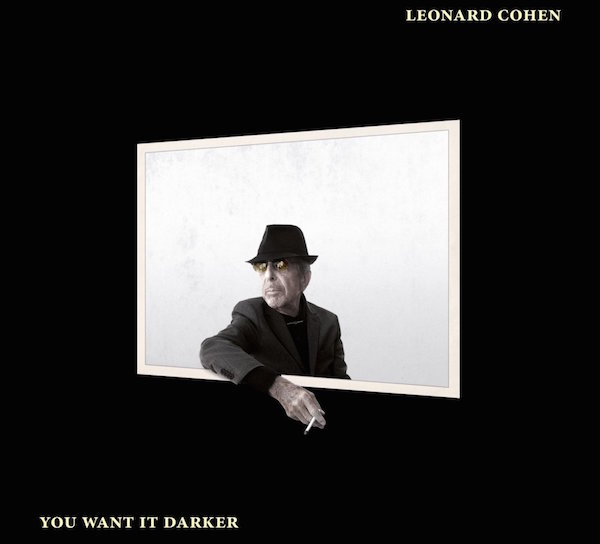

The late work of substantial artists tends to be about self-discovery — it is about deepening their style and intensifying their customary themes. Maybe it’s due to intimations of the dying of the light, or the intolerance of bullshit that comes with age, but something elegant though severe rises to the surface. Leonard Cohen’s ominously titled You Want It Darker, his 14th studio album, is at its best when it embraces this aesthetic toughing up.

At 82, Cohen seems to feel that there isn’t a lot of time left and that he has nothing to prove to anyone, least of all himself. Accordingly, You Want It Darker serves up a calm but rugged resignation amid its darkness. Clocking in at a brisk nine songs in a little over thirty minutes, the legendary perfectionist isn’t mincing words or striking death’s head poses for the media. He corrected a recent extensive profile in the New Yorker that quoted him as saying that he was ready to die. Still, at this point Cohen’s songwriting has become undeniably pensive.

With its acidic notes of moral outrage, “You Want It Darker” is by far the best song on the album, questioning Abraham’s response to God’s summons at both the burning bush and the sacrifice of Isaac (“hineni” or “here I am”). The lyrics shake a fist at the cruelty of the 20th Century and seem to point an accusing finger at the diffidence of the man upstairs: “If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game/ If you are the healer, that means I’m broken and lame … Magnified, sanctified, be thy holy name/ Vilified, crucified, in the human frame/ A million candles burning for the help that never came/ You want it darker.”

Cohen’s rueful sense of humor is still intact, though it turns into bitter here, in lines such as “I’ve seen you turn the water into wine and then back into water” and “I struggled with some demons/ They were middle class and tame/ I didn’t know I had permission to murder and to maim.” Cohen’s writing has always thrived at the bloody crossroads of belief and non-belief; having gone through intense periods of study and meditation (Judaism and Buddhism) as well as the romantic pursuit of more secular pleasures, he’s experienced these conflicting worlds from both sides. At this point, his voice has the hard-earned weariness of the seeker who has ceased his searching.

In the wry ditty “It Seemed The Better Way” his words reflect on his years at Mount Baldy studying under Zen master Roshi (Cohen’s former guru, who ended up being accused of various forms of misconduct with the female staff). “Seemed the better way/ When I first heard him speak/ But now it’s much too late/ To turn the other cheek/ Sounded like the truth/ Seemed the better way/ Sounded like the truth/ But it’s not the truth today.” It must have taken a lot to say that, considering the rigorous years Cohen spent in Roshi’s monastery.

Still, Cohen hasn’t given up on meditation and the years he spent searching for illumination: “Steer your way past the ruins of the Altar and the Mall/ Steer your way through the fables of Creation and The Fall/ Steer your way past the Palaces that rise above the rot/ Year by year, month by month, day by day/ Thought by thought.”

Some of the songs dangle precariously over the pit of cliché, such as “Traveling Light” and “Leaving the Table,” tunes that extend the “the holy game of poker” line from “The Stranger Song,” written many decades ago, into a too-easy metaphor. The song “If I Didn’t Have Your Love” sticks too close to greeting-card sentiment. His refusal to dive deeply into the nature of desire is disappointing because, when it comes to love, there aren’t many songwriters who have given it such redemptive power and describe it with such subtle complexity.

Approaching the end of a long career, Cohen remains spry enough to tackle themes cosmic and romantic, his humor is still deftly wry, and his anguish all-too-human. Still, there is that sense of an ending. In the last song on the album, Cohen wishes for “A treaty we could sign/ Between your love and mine.” It makes the listener wonder what battle he might still be fighting, and why he keeps losing it after all these years. He has become skeptical about whether there is anything left to believe in. Yet the best moments of You Want It Darker bring a Beckettesque grandeur to failure: being able to sing about defeat is enough.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

A thoughtful, eloquent review–and a pitch-perfect ending.

I was listening to David Crosby’s interview with Marc Maron the other day and I thought about what a shame it is that so many of the greatest singers and musicians of the 60’s and 70’s are passing away or are quite close to it, like Cohen is. My girlfriend is teaching college physics and when she mentioned that Dylan got the Nobel, one of her students revealed that she didn’t know who Bob Dylan was. I’m no Boomer, but I treasure a lot of the music of the sixties aside from its hippie nostalgia for the dynamic, complex, and often challenging work it was. I’m glad people have been tuning in to Cohen’s writing and music in the past few years, but I wonder who is going to keep this music alive for the next generation?

Thanks for the kind words, Vince- I’m glad I got at least close to the tone I wanted.