Visual Arts Book Review: Critic Douglas Crimp — “Before Pictures”

Critic Douglas Crimp’s autobiography provides an absorbing, microcosmic look into the early days of the 1970s New York art scene.

Before Pictures by Douglas Crimp. 2016 Dancing Foxes Press/University of Chicago Press, 288 pages, $39.

By Timothy Francis Barry

When Walt Whitman wrote “Me, a Manhattenese, that most loving and arrogant of men,” he could have been peering into the future of art critic Douglas Crimp. And Crimp spells out what he loves most in his quirky and highly subjective autobiography, Before Pictures — contemporary art, modern dance, the disco-inferno of 1970s gay New York, critical writing and reading, Sundays in the park with George (or Christian, or Richard …).

And, in truth, Crimp’s love comes with a certain amount of arrogance, such as when he goes on at length about the different apartments he lived in, “deciding what drugs to take and what clothes to wear,” failed (and successful) writing projects, and what he whispered in someone’s ear at a party 40 years ago. The assumption is that the reading public will find all of this of interest.

That said, this reader found it an absorbing account, a microcosmic look into the early days of the New York art world circa the Seventies, when pluralism came of age and performance, new media, and installation galloped to the rescue of the virtually exhausted fields of painting, drawing, and sculpture. Crimp puts us there on the rapidly changing ground, writing about how he works with and, to his credit, humanizes, towering figures like Ellsworth Kelly, John Ashbery, Guy Hocquenghem, and Agnes Martin.

Crimp arrived on Gotham’s shores in 1967, a tall and curious art-history graduate from Idaho, who in short order finds a cheap apartment in an uptown building that is crowded with well-connected art-world types. Throughout his life he almost effortlessly parlays useful connections into social and career advantages. He relates each fortuitous happenstance after another with breathless humor:

“I set out one day from my Spanish Harlem apartment to go to the Metropolitan Museum, where I planned to apply for a job. As I walked down Fifth Avenue from Ninety-Eighth Street near Park Avenue, I came upon the Guggenheim, and thought to myself, ‘Here’s a museum, I might just as well try this one.’ I inquired of the first person I encountered in the lobby of what was then the administration wing about applying for a job. His immediate reply, to my surprise, was to ask, ‘Do you know anything about pre-Columbian Art?’ ‘Yes,’ I answered, ‘I studied it extensively in college.’ And so, after little further discussion, I was offered a job.”

Examples of Crimp as a consummate networker are littered liberally throughout the book. His occasional “tagging along” with Guggenheim curator Diane Waldman and her friend Elizabeth Baker on their Saturday afternoon gallery crawls led to Baker offering him his first writing assignment — at Art News, where she was managing editor.

It was with similar ease that he fell in with Rosalind Krauss, Craig Owens, and the rest of the October magazine crowd. That famously obtuse journal was where he made his serious bones as a critic, though, as he admits disarmingly, he was “never as fluent in Continental theory (not to mention the French language)…. I left my reliance on Derrida implicit.”

Immersed in the art world as he was, and acquainted with pretty much every interesting artist in New York, his lateral move into exhibition curating in those years came organically. Crimp warmed up by organizing Agnes Martin’s first solo show at a noncommercial space, the School of Visual Arts gallery, but it was his next effort for which he will be most remembered.

The book’s title Before Pictures refers to the 1977 “Pictures” exhibition at New York City’s Artists Space, which Crimp organized with the assistance of the gallery’s director, Helene Winer. It featured a group of artists who used appropriated images from the media — Troy Brauntuch, Philip Smith, Jack Goldstein, Sherri Levine, and Robert Longo — though it famously ignored the two artists most closely identified with what is now termed The Pictures Generation, Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince.

Crimp admits he dropped the ball there: “Looking back now at the list of artists I considered, Sherman’s name stands as a kind of rebuke,” he writes. At a reading and Q & A session recently at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Crimp pointed out that “the legend that has continued to grow surrounding the Pictures exhibition seems actually greater and more important than the actual exhibition.”

At an exhibition accompanying and celebrating Before Pictures’ publication at New York’s Galerie Buchholz, works and documents from that Pictures exhibition raise some questions about its enduring value. Certainly the impulse toward media-critique and institutional-critique that sprang from these works and artists shows no signs of slowing down. However, many of the works from that time have taken on a dated, creaky quality; for instance, the 90-minute black-and-white video of Yvonne Rainer’s stage-performance will likely find few rabid fans.

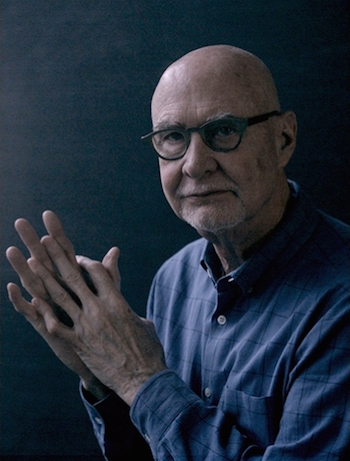

Douglas Crimp. Still from Douglas, video, 2015, James Nares.

As an exhibition keyed to a book, the Galerie Buchholz show is outstanding. The stark black-and-white photographs that conceptual photographer Zoe Leonard took for the volume are arrayed along one wall. They depict key locations in Crimp’s New York life: the gritty subway station walls in unsparing artificial light, the doorways of his buildings, captured with a neutral sensibility, rather more in the flat, unemotional manner of the Bechers than the romance of Cartier-Bresson’s decisive moment.

The editors of Before Pictures marry Crimp’s text to visuals masterfully; this could almost be classified as an artist’s book. One might make a case that the editorial reins could have been tighter, particularly with regard to the writing. Crimp’s obsession with the Watergate proceedings, detailed at length, comes across as filler. And do we really need to know exactly what transpired sexually between Crimp and this or that famous artist?

Well, maybe so — let the reader judge. Certainly, Crimp’s accounts of the vanished night world of the sexual outlaw and what happened in those abandoned buildings, in the back of parked trucks, and on lonely piers overlooking the Hudson River, are among the book’s most riveting moments. While other volumes have trod similar ground, such as David Wojnarowicz’s classic Close To The Knives, with Crimp we reap the benefit of a considered, retrospective view: he’s one of the few thoughtful observers who were there but are still alive, and he’s had 30 years to mull it over.

Also, perhaps his introduction to the pier photographs of the late Alvin Baltrop in Before Pictures will bring another phantom artist figure from the AIDS era back into the contemporary conversation. Baltrop’s matter-of-fact works — documenting the random sexual encounters of men — stand as touchstones of 20th-century anthropology, but are also in some cases spectacular compositional accomplishments.

Timothy Francis Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, both in Provincetown.

Tagged: Before Pictures, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Douglas Crimp, Galerie Buchholz