Music Interview: Jim Kweskin and Geoff Muldaur

Jim Kweskin and Geoff Muldaur are still mining America’s musical traditions.

(l) Geoff Muldaur and (r) Jim Kweskin — it seems inevitable that these two musicians would meet. Photo: Roman Cho.

By Ken Bader

Whenever Jim Kweskin and Geoff Muldaur take the stage at Club Passim in Harvard Square, they feel right at home — with the venue and each other. The two have been musical soul mates since the early ’60s, when the Jim Kweskin Jug Band frequently performed at Club Passim’s previous incarnation, Club 47.

The band’s repertoire ranged all over the map — from Memphis to Louisiana, from the Appalachian mountains to the Mississippi Delta. Kweskin told me by phone from his home in Los Angeles that the bedrock of it all was the music he grew up with. “My father had a collection of old records. Most of it was early jazz — Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, Louis Armstrong’s Hot Fives and Hot Sevens, Bessie Smith, a few Lead Bellys thrown in there — and I loved that music. I just loved it.”

By the time he began his freshman year at Boston University, Kweskin was also listening to the folk music of Pete Seeger, the Weavers, Burl Ives, and Josh White. It didn’t occur to him that folk and jazz could merge until one night at Club 47. “I heard Eric Von Schmidt playing the guitar and singing a Jelly Roll Morton song,” he says. “And I thought, this is fantastic. So that’s what I started to do, and it turns out to be what jug band music is anyway. It’s really just old-time blues and jazz played on folk music instruments instead of horns.”

Shaping the musical paths Kweskin and Muldaur would take was the Anthology of American Folk Music, a compilation of folk, blues, and country recordings from the late ’20s and early ’30s. Muldaur, who also lives in L.A., told me that the collection had an incredible impact on him. “When you look at these guys on the Anthology of American Folk Music, it was like, how could they be real? The music was so different. I’m growing up outside of New York listening to doo-wop and jazz, and then I’m hearing Lead Belly and this strange stuff from a mythical world that I didn’t even know existed.”

In retrospect, it seems inevitable that Muldaur and Kweskin would meet. They eventually did, in 1962. At the time, they were living in Cambridge, performing separately at Club 47 and elsewhere. Then, someone at the Community Church in Boston decided to put them together in a concert, to be called “The Bittersweet Blues of Geoff Muldaur and the Good Time Music of Jim Kweskin.” As Kweskin remembers it, “Geoff was to play half the concert, and I was to play the other half. So we decided to do a couple of songs together. That’s the first time we met.”

The Jim Kweskin Jug Band was about to be born. After a jam session with some local musicians at Club 47 one night, a gentleman came up to Kweskin and introduced himself as Maynard Solomon of Vanguard Records. Kweskin recalls their conversation. “He said, ‘How would you like to make a record with those guys?’ And I said, ‘Well, those aren’t my guys, but I’d love to make a record.’ So, basically, I had a record deal before I had the band.”

So Kweskin put the band together. “I needed a blues singer,” he says, “and Geoff is an amazing blues singer. I wanted to do the up-tempo ‘Rag Mama’ kind of songs and I wanted Geoff to do the bluesy stuff. I knew how good he was, so I asked him to join.” Muldaur accepted the invitation. For the next five years, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band injected a spirit of fun into the sometimes self-serious world of folk music, inspiring such groups as the Lovin’ Spoonful and the Grateful Dead, before disbanding. Kweskin went on to found a construction company in Los Angeles. Muldaur helped create software for the steel industry in Detroit. Both remained musically active.

Kweskin and Muldaur met up again in 2005 at a memorial concert for their former bandmate, Fritz Richmond, and found they still had the chemistry. Muldaur says, “I always get the feeling of the song and then come up with my own arrangement. It was sort of a Cambridge thing. Von Schmidt and Tom Rush were that way. You hear a tune and then you find your own way to do it. Jim’s more of a songster. He knows hundreds and hundreds of songs. So he mostly wants to do the song. So the combination of us — where I let him just do the song and I say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, we gotta do this with it’ — works very well.” The two have performed together frequently since that rendezvous in 2005.

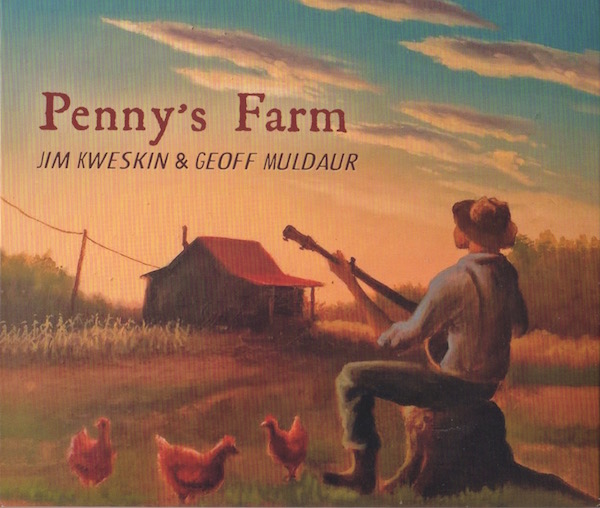

More than 50 years after they first started making music together, Kweskin and Muldaur finally recorded a duo album, Penny’s Farm. The cover, painted by Anthony Benton Gude, a friend of Kweskin’s and the grandson of Thomas Hart Benton, sets the rustic mood of the music within. Kweskin and Muldaur return to the Anthology of American Folk Music for several of the songs. One is “99 Year Blues,” which Muldaur says showcases his collaboration with Kweskin. “I was hanging around with Jim, maybe five years ago, and he played that, and I went, Oh my God, he just does that so well, so beautifully! And then later, I said, ‘You know what? I could do some things with that song that would be different.’ And so, little by little, I find parts that are very personal and complement what Jim has done. I feather it with this stuff I hear in my head.”

Muldaur cites another song on Penny’s Farm on which the partnership jelled. “I came up with an arrangement of ‘Fishing Blues,’ and Jim worked up a whole harmony part on the guitar that was so special. And for some reason we sing well together, too.”

The album ends with a live version of “Frankie.” Kweskin says he fell in love with the Mississippi John Hurt tune the first time he heard it on the Anthology of American Folk Music. “At the time, I was just learning how to fingerpick on the guitar. And I loved that song so much, I decided I wanted to play it. By the time I got finished learning how — and it took months — I could fingerpick pretty good.”

Kweskin and Muldaur have been playing this kind of music for decades and, for all the fun they have, Kweskin says they take it very seriously. “There’s this wonderful old music — traditional folk music, mostly American — that we want to keep alive. We want to pass it on to future generations so that it keeps going. That’s what we were doing back when we were young, and we’re still doing it.”

Whether future generations will keep the music going is uncertain. Geoff Muldaur is not reassured when he looks out at his audiences. As he puts it, “I play for old people and their parents.”

Ken Bader has been a Senior Editor with NPR, WBUR, and WGBH.

Tagged: American Folk Music, Club Passim, Geoff Muldaur, Jim Kweskin, Ken Bader

I googled jim kweskin earlier today on a whim and was glad to see he’s still going strong. He taught me to finger pick in ‘63 while I was at Harvard summer school and I took what I learned to Michigan State where I did graduate work in physics, but also played music and was part of the Glad Dog Jug Band – just found a cassette tape of the band playing at the Ann Arbor folk festival. Great memories, and all based on Jim Kweskin’s finger picking charts – I still have them. So thanks, Jim, for helping me start on a lot of musical fun! Chuck Taylor