Book Review: “Digging Up Mother” — Bizarro Family Values

Digging Up Mother: A Love Story, is a disarmingly funny, unexpectedly sweet memoir. Stanhope forges a special brand of funny-sad, and doesn’t flinch when the events become sad-sad.

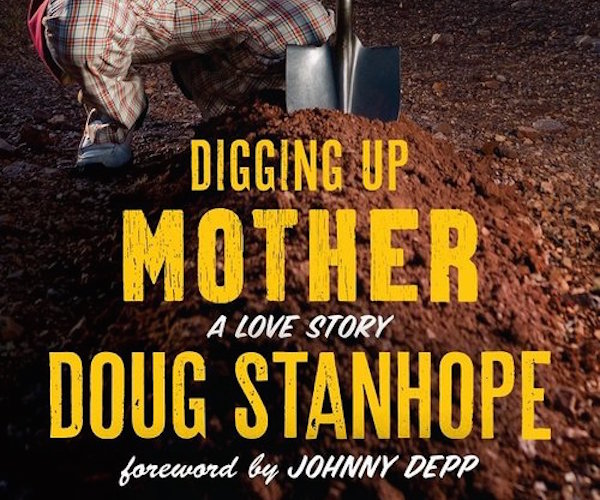

Digging Up Mother: A Love Story by Doug Stanhope. Da Capo Press, 336 pages, $25.99.

By Betsy Sherman

Do a Youtube search for “Doug’s Mother Reviews Porn,” and the late great Bonnie [Stanhope] Kirk demonstrates how she was “not your typical mother,” a phrase she loved to say. The review segment on Comedy Central’s The Man Show, when it was hosted by son Doug Stanhope and Joe Rogan, was a public glimpse of a one-of-a-kind mother-son relationship. It’s at the heart of Digging Up Mother: A Love Story, a disarmingly funny, unexpectedly sweet memoir. Stanhope forges a special brand of funny-sad, and doesn’t flinch when the events become sad-sad.

Stanhope went from initial fame on the doomed post-Jimmy Kimmel/Adam Carolla Man Show to more valuable renown as a comic’s-comic, respected for unvarnished candor and for pulling audiences out of their comfort zone. Just one example: he appeared near the end of The Aristocrats spinning the profane title joke into the ear of a baby. Currently, Stanhope hosts The Doug Stanhope Shotclog Podcast from a bar in his adopted home of Bisbee, AZ (population c. 5000). His 2016 stand-up tour will hit Boston with a December 1 show at the Wilbur Theatre.

Digging Up Mother manages to be a friendly read while still fulfilling the author’s usual mission of steering clear of the comfortable. Don’t expect pampering here: in the opening chapter, Stanhope relates the circumstances of 63-year-old Bonnie’s death from emphysema in a hospital bed in Doug and his girlfriend Bingo’s house. The plan is that Bonnie will self-administer an overdose of pills when she doesn’t want to suffer the pain anymore. As the hours pass, absurdities are pointed out—the breast implants his mother used to boast about, writes Doug, now look like bowling balls on a skeleton—and gallows humor is an essential and long-established coping mechanism.

In a passage about his childhood, Stanhope notes that “not many parents will defend you for having a morbid and profane sense of humor.” He asserts that he owes his “dark storytelling” to his mother’s proudly sick sense of humor. Bonnie, an alcoholic, used to take her son to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings during his formative years. He says of the “performers” at the meetings, “They were all bruised to some extent but they flaunted their scars. They swore and they smoked and they told you about real shit. Half of ‘em were probably full of shit but that didn’t matter at the time. They were exciting.” The future comedian also cribbed jokes from his mother’s copies of Hustler.

Stanhope grew up in Worcester, MA (but he was never a Boston comic—he went way west, rather than a few miles east, to start his career). Whereas his mother had a big, brassy personality, his father was easygoing and conflict-averse. Doug’s parents divorced when he was 6 or 7. His brother was closer to their Dad, but Doug came to develop an intense emotional connection with Mother (which is his preferred term, rather than Mom): “There was something weird between us. We got along like best friends. We wrote to each other like lovers.” They lived to make each other laugh.

Stanhope tells tales from his non-studious, prank-obsessed school years. During this time, Bonnie became a tractor-trailer driver (coolest mother ever!). After he turned 18, with a conviction that now baffles him, Stanhope moved to Los Angeles, sure that he could make it as an actor. Meanwhile, Mother moved to Florida and became a massage therapist.

Digging Up Mother charts the turnover of significent things in Stanhope’s life: girlfriends, jobs, buddies, cars, apartments, drugs of choice, dive bars. Through the many changes, there was one constant, the passion between him and Mother. He didn’t make it as an actor on the Coast in the traditional sense, but his triumph there did take a similar talent. It was the late ‘80s, a golden age of telemarketing scams, and Stanhope became a star huckster in “phone rooms,” first in California, then in Las Vegas. Bonnie was proud of her son’s rise up the bullshitters’ ladder. Doug and some friends set up their own phone room in Idaho. It was there that he did his first open mike at a comedy club and found his calling. The decade’s comedy boom was winding down, but Stanhope persevered, became a road comic, and then looked to catch a break back in L.A.

Bonnie and Doug each suffered heartbreaks and disappointments, but it took Stanhope a while to realize that his mother was finding it particularly hard to bounce back, to the point where she was suffering from depression (in order to write the book, he drew on diaries and letters that he wasn’t privy to at the time). He did know, especially after he moved her to L.A., that she was turning into a reclusive hoarder, obsessed with her cats. Moreover, she had gone from being someone who was generally accepting of all kinds of people to being a negative-spirited racist (“Mother seemed to hate everything but me”). On the brighter side, Bonnie acted in a few independent films, two of them directed by Tamar Halpern, who contributes some passages to Stanhope’s memoir about her “refreshing” discovery (“She wasn’t an act. She was real and fuck anyone who didn’t appreciate it …”). Eventually Stanhope, fed up with showbiz’s company town, discovered Bisbee, moved there, and moved the ailing Bonnie there. And so the head and tail of the book merge, and we view the ordeal of Bonnie’s death with a new, invested perspective.

If Artie Lange’s rollicking memoirs portraying a comedian moving through the circles of hell are the gold standard of the genre, Stanhope earns a firm silver medal. Throughout Digging Up Mother, Stanhope is amusingly self-deprecating, for example comparing his posture to that of a seahorse (“I’ve had the hunched spine of a defeated man”), and occasionally self-lacerating. But the narrative’s purpose is, by the end, kind of noble. The book portrays how a boy grew to manhood with an unorthodox means of moral support, how a career sprouted and grew, and the bizarro family values that underlie both the life and the work.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Betsy Sherman, Da Capo Press, Digging Up Mother: A Love Story