Book Review: “New England Bound” — Slavery and the Puritans

New Englanders could let slavery go because it was not worth the embarrassment of defending it. When a sin does not make you rich, your moral clarity can be much greater.

New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America, by Wendy Warren. Liveright, 352 pp., illustrated, $29.95.

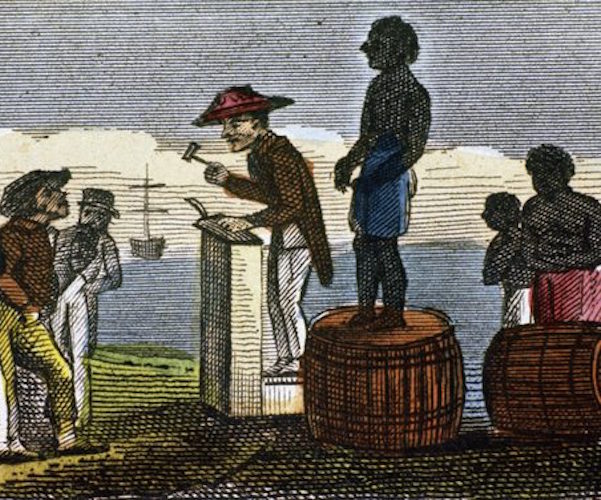

Slaves in New England — The first slave code in America was written in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641. Photo: Wiki Common.

By David Mehegan

In the sectional conflict that led to the Civil War, one of the standard apologias of the slave owning southern interest was that black people held in bondage were treated better than the wage workers of the North. They were cared for from cradle to grave, it was argued, in the bosom of gentle masters, whereas in the heartless factories of the industrial North, workers were ruthlessly oppressed at work and cut loose to fend for themselves when there was no work. This was nonsense; not that there were no benign southern masters, but that not even the most wretched wage-worker was bought and sold like livestock.

What the slave-owners did not think to note, and therefore the Yankee opponents of slavery did not have to defend or explain, was that the slave system had started in New England, thrived here for more than a century, and brought wealth and position to many a great New England family. This is the story that Wendy Warren, a Princeton historian, tells fully, thoughtfully, and vividly. While in the back of our minds we had always known it was true, nothing brings it home like the sequence of cruel and heartbreaking stories she tells, of slaves as mistreated as Solomon Northrup in Twelve Years a Slave, with the difference that the setting was not some steamy plantation but towns with such names as Boston, Cambridge, Scituate, Dorchester, and Salem.

The first slave code in America was written in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641. Titled “The Body of Liberties,” it provided that “there shall never be any bond-slavery, villenage, or captivitie amongst us; unless it be lawfull captives, taken in just wars, and such strangers as willingly sell themselves, or are sold to us.” [sic] That last phrase allowed not only the free importation of African slaves, who were held in perpetual bondage — along with their progeny forever — but the trade in slaves around the Atlantic world by increasingly prosperous New England entrepreneurs. Such merchants voyaged to West Africa, purchased slaves, and carried them to Barbados, where they sold them into the brutal sugar plantations for tobacco, rum, or molasses, then returned to New England. Thus New Englanders plied the slavery business, even though they brought relatively few slaves home with them. In 1680, former Massachusetts Governor Simon Bradstreet, widower of poet Anne Bradstreet, estimated that “Now and then, two or three Negro’s are brought hither from Barbados and other of his Majesties plantations, and sold here for about twenty pounds apiece.” He placed the number of slaves in the colony (he owned two women himself) at “about one hundred or one hundred and twenty,” a number Warren believes to be greatly understated.

Bradstreet was not the only famous name implicated in the commodification of human flesh: the sons of John Winthrop — he of the pious sermon about creating a “City on a Hill” in New England — were active in the slave-based economy of Barbados, including the procurement of Indians and Africans to work therein. Cotton Mather and his son, Increase, were enthusiastic slave-owners. One of the worst, to this reviewer’s mind, was Boston’s Samuel Maverick, immortalized by East Boston’s Maverick Square. In 1638, he owned three Africans, two women and one man. “Desirous to have a breed of Negroes,” a witness wrote, but finding that the African women would not willingly consort with the man, Maverick ordered the man to rape one of the women, which he did. Warren writes, “After the attack, the distraught woman came to the window of another Englishman … and complained in a ‘very loud and shril’ [sic] voice about the assault. The woman took the attack,” the neighbor wrote, “’in high disdain beyond her slavery,’ and it was ‘the cause of her grief.’”

It is clear from early records that slaves at first were as likely to be native people as Africans. After the Pequot War of 1637 and the even more violent and terrible King Philip’s War of 1675, the captured warriors and their women and children were mostly sold into slavery. In the accounts of those acts and events, we catch a clear view of the kind of people many of the Puritan leaders were, in whom religion mixed easily with inhumanity. After the decisive battle of King Philip’s War, a party of 150 Indians surrendered to a Plymouth Colony garrison. Almost all were sold into slavery. One young man had carried his elderly father into the stockade on his back. After the youth was sold, the English were in a quandary as to the fate of his “decreped” [sic] father, who had no monetary value. Rhode Island deputy governor John Easton wrote, “Sum wold have had him devoured by Doges, but the Tendernes of sum of them prevailed,” so instead they “cut off his Head.”

Tenderness? It is endlessly amazing what barbarities that some “Christians” supposed would be blessed by the protagonist of the New Testament. Warren quotes Perry Miller, the great 20th century scholar of the New England Puritans: “Piety made sharp the edge of Puritan cruelty.”

The bulk of Warren’s book, which focuses primarily on the 17th and early 18th centuries, is devoted to detailed accounts of particular individuals, both owners and slaves, as revealed in court documents. These accounts, and her close readings of their subtexts, bring the experiences of enslaved people to life for us in a way that no broad and general account of slavery could do. As she tells a story, she asks the reader to imagine with her what this life must have been like. For instance, the story of Hagar:

Hagar, a woman slave in New England, in 1669 was found to be pregnant and brought to trial for fornication. She named her owner’s son as the father, and then added that she had also had relations with another slave. In self-defense, having the public eye of a courtroom, she complained bitterly that she had been stolen from her husband and three-year-old son in Angola, shipped to Barbados, then sold to New England. In Puritan law, war-captives could be enslaved, but out-and-out kidnapping (“man-stealing”) was illegal. Nonetheless, Warren says that magistrate Thomas Danforth, himself a slave owner, took no action to investigate her claim; “Hagar’s story was beyond his remit.” It was also beyond his capability to investigate the details of her capture on the other side of the ocean, in the interior country of Angola. Furthermore, it was irrelevant; the salient fact in the local law’s realm was that she was a slave, purchased in some manner by a local resident, accused of violating the moral code of the English. By the sharp-edged piety of the Puritans, what she did was important; what was done to her could not be questioned.

Warren explores the implications of the case, especially the cold indifference to Hagar’s history, notwithstanding the Puritans’ usually tenderhearted view of family relations. Whether in New England or Barbados, the wealth invested in an owned life trumped almost any moral scruple or human feeling. Warren writes, “The embrace of chattel slavery in the region meant, almost by definition, that New England’s colonists violated time and again the personal relations of the people they owned.”

Of those lonely enslaved people accused of sexual misdeeds, she writes, “New England antifornication codes failed spectacularly to legislate sexual behavior among those barred from marriage. There is something touching in that failure, something perhaps admirable about the determination of enslaved people to have liaisons, to form connections in a world determined to deny them such acts…The threatened and real whippings and humiliations almost certainly did prevent other enslaved and indentured New Englanders from stealing away to the meadow or climbing through an open chamber window. All of them, those who stole away and those who did not, were thus kept from settling into something more stable, into what might well be thought of as family life. But even that recognition falls short of comprehending the rank tragedy that resulted from enslavement — the root problem was … that those enslaved in seventeenth-century New England had already been rent from any family they had. The problem was that they were in English homes at all.”

It is not surprising that Warren strains to find words to “comprehend the rank tragedy that resulted from enslavement,” the criminality and barbarism of it. Over the course of the book, her deploring of it, as in this instance, begins to feel repetitive. What is there to say beyond that slavery is really, really a monstrous thing? Perhaps it does not need to be said explicitly; the cold facts are sufficiently terrible. The book is full of such cases as Hagar’s, some even more awful, each one carefully palpated for its pathos and injustice.

Poignant as these cases are, Warren has a curious way of disgorging more speculation about motives and feelings than is useful, while leaving out basic factual details. In the Hagar case, she gives the name of the owner’s accused son — John Manning — but not that of the owner. She does not say exactly where the events occurred, other than New England, nor does she reveal the final disposition of Hagar’s case. (If she had been writing for a newspaper, her editor would have asked, “What happened to Hagar?”) Even if those facts are not known, she might have said as much.

It is beyond the writ of this book to explain the total revolution in New England opinion about slavery in the succeeding centuries, a change which famously did not happen in the southern colonies. Warren does not tackle this intellectual and moral revolution; it probably deserves a book of its own. However it happened, by the time of the abolition movement of the 19th century, it appears that the ethos of the age had almost forgotten the cruel facts of early bondage. Warren cites Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose writings show little awareness of the Puritans’ ownership of human chattels.

To be sure, writes Warren, there had been early stirrings of conscience, the most famous of which was a 1700 pamphlet by Boston Judge Samuel Sewall, “The Selling of Joseph,” an anti-slavery manifesto which was little noticed and soon forgotten. But Sewall was unique. In marked contrast to Danforth and others, he publicly repented of and begged forgiveness for his part as a judge in the witchcraft hysteria.

Author Wendy Warren. Photo: Denise J. Applewhite.

In Massachusetts, slavery was finally abolished, not by legislation, but by order of the Supreme Judicial Court in 1783, a result of the suit of Quock Walker, who argued that his bondage was illegal under the new state constitution of 1780. Chief Justice William Cushing wrote, “The idea of slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution; and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature, unless his liberty is forfeited by some criminal conduct or given up by personal consent or contract.”

We proud Yankees might prefer to locate the reason for this moral conversion in some superior sense of humanity or religion, as against that of the South. The real reason more likely is that slavery was never an important economic engine here, as it became in the great cotton, sugar, and tobacco economies. Slaves were never numerous here, and were house servants or skilled craftsmen more often than farm hands. In commercial New England, unlike the agrarian and semi-feudal South, no one’s whole wealth depended upon human livestock.

Warren notes that in “The Selling of Joseph,” Sewall had located the moral fault of slavery not in the mistreatment of enslaved people, but in the fact of purchase: “Sewall held out for especial opprobrium not incidents of torture but the moment of commodification.” One-hundred-fifty years before the pro-slavery argument that slaves were humanely treated by their masters, Sewall had put his finger on the heart of the matter: the primal sin was not abuse, but the turning of human beings into a species of exchangeable coin. As the local value of that coin declined, New Englanders could let slavery go because it was not worth the embarrassment of defending it. When a sin does not make you rich, your moral clarity can be much greater.

Of course, hereabouts we see in recent days a greater sensitivity (greater even than the abolitionists had) to that early history of human bondage and commodification, with for example the recent decision of Harvard Law School to alter its seal, a legacy of the slave-owning Royall family. That historical self-examination is sure to continue, with other proposed changes in New England names or symbols. Allow me be the first to suggest this one: the renaming of East Boston’s Maverick Square (and T station). How about Quock Walker Square?

David Mehegan is a contributing writer. He can be reached at dmehegan@bu.edu.

Tagged: Liverwright, New England, New England Bound, Puritian, seventeenth century, Slavery, Slavery and Colonization in Early America, W.W. Norton