Book Review: Marceline Loridan-Ivens’ Memoir of Surviving the Nazi Death Camps

In contrast to similar extermination-camp memoirs, But You Did Not Come Back focuses on the affliction of women.

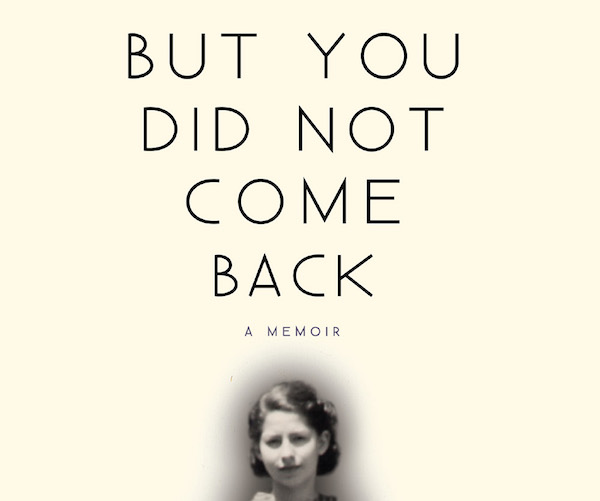

But You Did Not Come Back by Marceline Loridan-Ivens (with Judith Perrignon), translated by Sandra Smith, Atlantic Monthly Press, 112 pp., $22.

By John Taylor

Filmmaker Marceline Loridan-Ivens’s memoir about surviving the Nazi extermination camps necessarily resembles, in its gruesome details, other books that tell the same story. Yet it also has a personal slant that is worth underscoring. Published to great success in France last year as Et tu n’es pas revenu, the book is actually a letter written to the author’s father, Shloïme Rozenberg (1901-1945), who did not survive.

Marceline (b. 1928) and her father were arrested one night in March 1944, as she was turning sixteen. Her mother and siblings were hiding when the Gestapo and the French Milice arrived at the château that the Rozenbergs had rather recently bought in the Vaucluse. Her father, who had run a sweater factory in Nancy, had imagined that he would be safe in the so-called Free Zone and believed, as Loridan-Ivens also speculates, that the village mayor and police chief would warn the family of imminent danger. Deported together, first to prisons in Avignon and Marseille and then to the transit camp of Drancy, father and daughter were eventually separated when Shloïme was sent to Auschwitz and Marceline to nearby Birkenau. They had been in the same cattle car on Convoy 71, along with another teenager who would become a famous French minister and European stateswoman: Simone Veil (b. 1927).

At the onset of her story, Loridan-Ivens avows that she has long been haunted by a message that her father managed to pass to her from his cellblock in Auschwitz to hers in Birkenau:

I can picture the note you managed to get to me back there, a stained little scrap of paper, almost rectangular, torn on one end. I can see your writing, slanted to the right, and four or five sentences that I can no longer remember. I’m sure of one line, the first: “My darling little girl,” and the last line too, your signature: “Shloïme.”

Unfolding in no linear fashion, the memoir spirals off from these last words conveyed by a father to his daughter: the affectionate salutation, the Polish-Yiddish first name. Loridan-Ivens keeps coming back to these words and analyzing the paternal feelings they possibly represent, all the while describing other scenes from her internment in Birkenau and, subsequently, Bergen-Belsen and Raguhn, a Junker airplane factory near Leipzig.

The author isn’t interested in filling out her tale with forgotten details so much as getting at her state of mind both back then and throughout the decades that follow—up to the present day. As the narrative moves back and forth in time, she explores how such a traumatic past never vanishes into oblivion, but remains constantly present. She especially ponders what her father, deep down, might have been like. When she was sixteen, she couldn’t really know.

It has often been pointed out how the death camps left indelible marks on the tattooed arms and forever disturbed minds of the survivors; less often, how the Shoah affected Jews who might have been deported and exterminated, but were not. Loridan-Ivens defines this as being “sick from the camps without ever having been there.” After the war, her brother Michel gradually goes mad and finally commits suicide. Her sister Henriette later kills herself as well. Upon the author’s return to France, her mother fails to go to Paris to pick her up at the Hotel Lutetia, where the survivors are temporarily housed, nor even to the local train station to meet her when she arrives in the south of France. She describes her mother as “one of the kind [. . .] who block out their emotions, transforming them into laughter or anger.” The author adds: “She didn’t understand where I was coming from, or didn’t want to.” Sometimes the mother was incredibly insensitive:

Almost immediately, Mama very quietly asked me if I’d been raped. Was I still a virgin? Good enough to be married off? That was her question. That time, I did resent her. She’d understood nothing. Back there, we were no longer women, no longer men. We were the dirty Jewish race: Stücke, stinking animals. We stripped naked only when they were deciding when we’d be put to death.

In contrast to similar extermination-camp memoirs, which necessarily relate familiar instances of Nazi brutality and the same strokes of pure luck that kept a few prisoners from the gas chambers, But You Did Not Come Back focuses on the affliction of women. The effects of suffering and depravation were devastating and sometimes permanent. “I never had children,” Loridan-Ivens explains, “I never wanted any.”

The body of a woman was distorted by the camps, forever. I find flesh and its elasticity horrifying. Back there, I saw skin, breasts, and stomachs sag, I saw women hunched over, crumpled up, I saw bodies deteriorate so quickly, become emaciated, disgusting, the road to the crematorium. [. . .] Not a single woman got her period anymore. [. . .] Motherhood had no meaning anymore.

Other details reveal lasting wounds with profound psychological implications: upon her return, the author can sleep only on a wooden floor, not in a comfortable bed, and her friend Simone Veil steals spoons from restaurants, flashing back to the death camps, where theft aided survival.

There are two moments of unexpected humaneness. The first occurs when an Austrian soldier in the Wehrmacht weeps when he sees that the father and daughter have been arrested: Marceline looks like his own redheaded daughter. He secretly warns them about their forthcoming doom in the death camps, encouraging them to escape by any means. The second moment takes place in Raguhn, where the women prisoners are given striped dresses with a red cross on the back and a yellow star on the chest. The women guards from the countryside provide needles and thread so that the prisoners can make the dresses fit better.

After the war, Marceline marries Francis Loridan, an engineer, but the couple lives apart after the husband departs for a job in Madagascar. They later divorce. She then marries Joris Ivens, the famous leftwing Dutch documentary filmmaker (1898-1989). She decides to bear the surname Loridan-Ivens, though she tells her father, in her letter, that she often specifies that she is “née Rozenberg.”

Distancing readers from the Shoah, the passages concerning Ivens are nonetheless pertinent to the author’s death-camp years in two arguable ways. First, Ivens was her father’s age, but not, seemingly, a surrogate father for her—though she herself raises the question. Secondly, their joint cinematographic projects probably enabled her to lose herself in work that temporarily—only temporarily—supplanted her terrifying memories of the death camps.

This being said, the last twenty pages of the book are comparatively weak. Her moving reminisce goes out of focus as Loridan-Ivens comments on the relationship of filmmaking and political issues, or on her ideological viewpoints, which did not always coincide with Ivens’s. It’s true that politically committed filmmaking became an essential part of her life. By means of her letter, she wants to tell her father about this development in her adult life.

It’s also tragically true that anti-Semitism and religious conflict, as she points out, once again represent major threats to contemporary France. The book ends with a question as harrowing as it is fundamental. She asks her sister-in-law, also a survivor: “Now that we are approaching the end of our lives, do you think it was a good thing for us to have come back from the camps?” The sister-in-law abruptly says no. Loridan-Ivens is inclined to agree, but she has not entirely given up the possibility of replying yes, and hopes that someone will again ask her the question on her deathbed.

John Taylor’s essays have been collected in five books at Transaction Publishers: Into the Heart of European Poetry, A Little Tour through European Poetry, and the three-volume Paths to Contemporary French Literature. He has translated numerous French-language poets, most recently Philippe Jaccottet, José-Flore Tappy, Pierre Chappuis, and Georges Perros. He lives in France.

Tagged: But You Did Not Come Back, Holocaust, Marceline Loridan-Ivens, memoir