Film Review: “Call Me Lucky” — An Extraordinary Portrait of Satirist Barry Crimmins

A labor of love that’s more than merely that, Call Me Lucky is one of the few great movies to come out so far this year.

Call Me Lucky, directed by Bobcat Goldthwait. Playing at The Somerville Theatre, Somerville, MA.

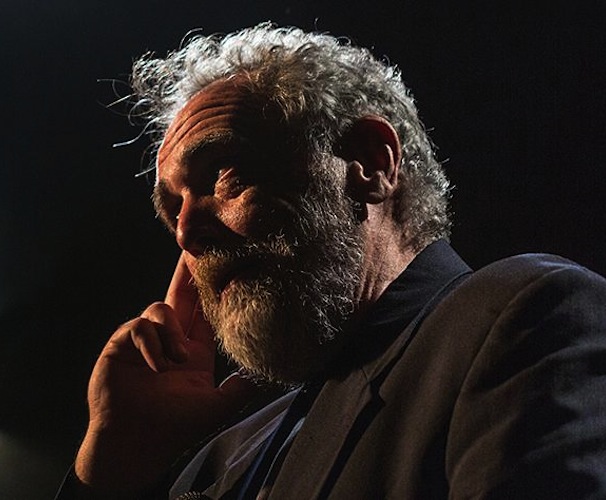

Barry Crimmins in “Call Me Lucky,” a documentary based on his life and career.

By Betsy Sherman

Bobcat Goldthwait – comedian, actor, TV director (Maron, among others) and lately one of the most interesting independent filmmakers around — makes his documentary debut with Call Me Lucky, a portrait of his friend and mentor Barry Crimmins. The performer-writer has been one of the country’s sharpest political satirists over a span of nearly four decades. Goldthwait’s cannily crafted feature examines the building blocks of its subject’s world view and shows how, and to a degree why, he’s been questioning authority and seeing what’s possible beyond the status quo all his life. A labor of love that’s more than merely that, Call Me Lucky is one of the few great movies to come out so far this year.

Anyone who’s seen the fabulous documentary about Boston’s role in the comedy boom of the ’80s, When Stand Up Stood Out, or was part of those rowdy good-old days, will remember the crucial role played by Crimmins. Comedy clubs were a new thing when he established one in an Inman Square Chinese restaurant called the Ding Ho. Like that film, Call Me Lucky applauds Crimmins’ role as a godfather of the scene who encouraged fledgling stand-ups (including Goldthwait) to find their own individual voices and, not incidentally, made sure they got paid decently for their sets. In foregrounding the man, Call Me Lucky delves deeper into the complications within Crimmins, whom friends say was both a nice guy and an intimidating, often angry guy who, back in the day, drank heavily.

Interviewees include Marc Maron, Paula Poundstone, Steven Wright, Kevin Meaney, and Goldthwait himself. When he was around 15, Syracuse native Goldthwait and best friend Tom Kenny (now the voice of Spongebob Squarepants) gave comedy a try at a club Crimmins was booking. At the time Crimmins was known as Bearcat, so Bob and Tom made fun of him by becoming Bobcat and Tomcat. Crimmins’ encouragement changed their lives, and they followed him when he moved to Boston.

The documentary camera and archival clips present the places Crimmins has called home. Primarily there’s rural upstate New York, where he grew up a nice Catholic boy (he was born in Skaneateles in 1953). Then there’s the comedy club stage — the film is peppered with shots of the gray-bearded comic venting hilariously about his backstory and about issues of today during a 2014 set at the Comedy Studio in Harvard Square. There are clips from the far-flung places in which Crimmins has walked the walk as a committed left-wing activist, such as Nicaragua during the ’80s, protesting U.S. backing of the contras, and Crawford, Texas, where he supports Cindy Sheehan’s effort to talk to George W. Bush about Iraq.

A compelling story, for sure, but Call Me Lucky builds toward the revelation of something that’s not exactly a staple of the genre: Crimmins’ repeated rape at the age of four by a man brought into the house by the family’s babysitter, and his subsequent crusade against child pornography in the age of easy access via the Internet.

Goldthwait and editor Jeff Striker have done an extraordinary job setting up and revealing this difficult subject matter (Crimmins first went public with his personal story during the 1990s). Early footage that finds Crimmins at his upstate New York home, surrounded by snow, introduces a minor-key feeling of solitude and reflection (Charlyne Yi’s score contributes to the mood as well). This thread is interwoven with the more raucous tales of starting out in show business. Crimmins reminisces about his days as an alter boy, and about avoiding the advances of a “Christopher Lee”-like priest. There are awkward exchanges between Goldthwait (heard off-camera) and one of Crimmins’ sisters that foreshadow that a boundary is going to be crossed.

Crimmins guides us through clips of his 1995 testimony at a Senate hearing entitled “Child Pornography on the Internet.” He had been alarmed when he came across AOL chat rooms in which pedophiles traded wares with their chums, and appalled by AOL’s indifference. The Senate panel (including, as Crimmins describes him, “pterodactyl” Strom Thurmond) shamelessly joke about their ignorance of the online world.

Knowing how wrenching it would be for his friend, but also believing it was essential for the film, Goldthwait arranged for Crimmins to revisit the basement of his childhood home, the scene of the crime. Standing under the light of a naked bulb, the large man is vulnerable, decrying the victimization of the trusting little kid that he was, but also grateful that he survived and did not himself become an abuser (“call me lucky”).

But hey, there are plenty of wicked funny moments in Call Me Lucky too. One involves Crimmins, wild-man comic Lenny Clarke and the home of Julia Child. And any observation from Steven Wright is a gem: he estimates that Crimmin’s impact is “like if Thoreau could have a computer.”

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in Archives Management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Barry Crimmins, Bobcat Goldthwait, Call Me Lucky, documentary, sexual abuse

[…] Goldthwait’s 2015 movie that targeted on the activist comedian Barry Crimmins (Arts Fuse overview), Pleasure Trip has its cameras and a focus set on two stand-up humorists: Goldthwait and his […]