Book Review: “Counternarratives” — Stories About History’s Metamorphosis

What John Keene has given us in Counternarratives is fearless fiction.

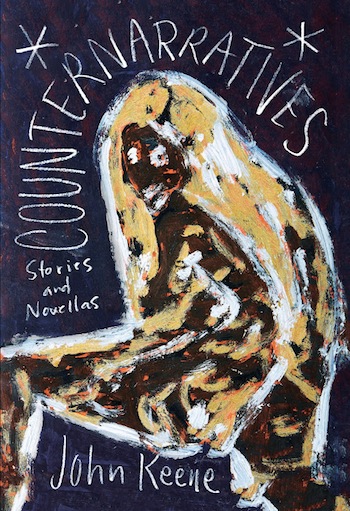

Counternarratives by John Keene, New Directions, 320 pages, $24.95.

Historical fiction is all well and good for novels, but there seems a decided bias against short stories set in the distant past. Literary journals are rarely interested in period pieces, and collections of them are almost nonexistent. “Contemporary,” it seems, is somehow conflated with “relevant.” Among modern authors, only three come to mind who wrote more than a handful of narratives set in previous centuries: Angela Carter (the Black Venus stories), Guy Davenport, and Jorge Luis Borges. Significantly, perhaps, all three have bid us their final farewells. With New Directions’ publication of Counternarratives, John Keene has taken up the challenge of orchestrating fictions that intimate how discernible motifs propagate through time.

The stories span centuries and continents, from 17th century Brazil to Depression Era Harlem. The tales set in the colonial Americas are recounted in a style reminiscent of the late Borges –formal, faceted, and angular to the point of crystalline. Also inherited from Borges, the narrator is often a temporally (and emotionally) distant observer reconstructing the past from various documents, including diaries, newspaper articles, medical reports, and scholarly tomes. In the tradition of Rimbaud’s voyant, however, Keene is not borrowing so much as picking up where — in this case — the Argentine master left off. While Borges’s narrators never come out of character, Keene’s do. The stories molt and shed and metamorphose. The voice that starts a narrative is frequently not the voice that finishes it. Indeed, there is an impressive range of styles in Counternarratives, from the ornately Victorian to the fragmentary postmodern.

Among Keene’s priorities is language itself. While the notion of the invisible brushstroke became passé among painters more than a century ago, “transparent prose” — composed of disposable sentences designed simply to move characters through plots and meant to vanish in the reader’s consciousness as soon as they are read — still dominates short fiction. Keene, however, weights his sentences almost as though he were composing lines of verse. “The morning light” in “Anthropophagy,” for example, “is too bright to bear except in blinks, winks, the armor of fished-out-of-pocket spectacles.” Here is a striking passage from the same vignette: “ … the hours fall away, disappear, he lying on his side, in dreams or awake and a record cycles on the player, Debussy, Villa-Lobos, Pixinguinha, or a disc grooved from the recordings of catimbo from his journeys across the northeast, its sonorities drumming out a bridge between the present and the past …” And in “On Brazil” Keene offers this description of Portuguese soldiers lost in the jungle: “Sheer, green walls of trees that smothered the sunlight rose before them. An interminable carnival of beast and birds crisscrossed the canopies above, while insects spawned in the pens of Satan swarmed the ground beneath their feet.” The description is not only elegantly accomplished, it is specific in its reflection of the collective psyche of foreigners — of Christian invaders.

The colonial stories are spiced with the European fear of the New World, the tendency, reflected in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s fiction, to demonize the wilderness and the indigenous people who inhabit it. Hints of this aversion to gloomy jungles and older rhythms are found in “A Letter on the Trials of the Counterreformation in New Lisbon,” an epistolary novella in which one of the monks inhabiting a small monastery in Brazil “had succumbed, allegedly, to the temptations of the Devil himself, and disappeared into the interior” (an allegation later addressed in greater detail). Sorcery, gender-shifting, and ancient rites brought by captive Africans haunt this narrative.

The protagonists in Keene’s fictions are often those whom history has overlooked or shunted to the side — slaves and their descendants: the only black woman Edgar Degas ever painted, Jim in an imaginative sequel to Huck Finn, a black teen helping to devise a use for balloons in the Civil War, a mute girl coerced by new masters to move from her native Haiti to Kentucky, a sailor and explorer from the Dominican Republic.

Keene is interested not only in marginal players, but also in obscure incidents, in the underside of history. “An Outtake from the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution,” for example, reminds us that slavery in the North (Massachusetts as it happens) was every bit as horrifying as slavery in the South. Zion, very likely a mulatto whose father was also his master, refuses — despite being severely and repeatedly beaten and sold off to new masters — to abide by the rules or the law and constantly runs off. One of his crimes, which speaks for itself, is “maserquerading as a free man.” The subtle irony in this story is that while the American colonists are preparing for a war triggered by unjust taxes and other economic restrictions imposed by the crown, they are entirely blind to the struggles of Zion and other slaves for the most basic of human rights.

If Keene’s characters and concerns defy the norm, so do his methods; his stories dispense with the sedate techniques practiced by writers from O. Henry to Raymond Carver. “On Brazil” is unique even among this volume’s collection of hybrids. It begins with a newspaper account of a present-day murder that is all but forgotten by the time we get to the end of the story, whose principle events take place in the 17th century. Cesarao, the leader of a plantation-wide slave revolt, escapes with his band of rebels and inadvertently becomes an obsession of his former master. There’s a principle of karmic boomeranging at work, an implication that the present moment is the culmination of a trillion trillion previous moments, that present events can be sourced to past events. The result is a story that reverberates with historical truth.

Then there is “Blues,” an imagined tryst between Harlem Renaissance poet, playwright (and even novelist) Langston Hughes and Mexican poet and playwright Xavier Villaurrutia. Lighter — despite its title — than many of the stories surrounding it, this one has a mercurial feel, flowing more like poetry than prose. Most of the secret to its power is in the language itself, the word choices, and the rhythm Keene sets. One of the things that helps him maintain this rhythm is his innovative use of ellipses. They function almost like line breaks (there are no periods in “Blues”), allowing him to dispense with grammatical formalities wherever they would dam the river. Here’s a sample:

“…he [Xavier] jots in his notebook that he enjoyed the train ride down along the coast … he sat on the south side as his classmate had recommended … observing the scenery of autumnal New York Sound … the water indifferent in its blue undulations … vanishing intermittently behind screens of greening trees and warehouses … he slipped down [from Yale] for the holiday the Americans celebrate to honor the Genoese Columbus … he would miss a single lecture …”

Author John Keene. Photo: Nina Subin/ Courtesy of the author and New Directions

It would be misleading to discuss this book and leave out the racism that appears in virtually every story — sometimes overtly, as in the narratives that deal with slavery, sometimes so subtly it is easily overlooked. In “Blues,” for example, when Villaurrutia returns to his Times Square hotel, he notices “the doorman’s gaze tracking him inside” — Villaurutia is Mexican after all. In “Acrobatique,” a mulatta trapeze artists displays so much strength in her performance that the dazzled crowd compares her to “an angel — or,” she wonders, “do I hear an animal?” “Unnatural” and “monster” also play across the surface of her hearing, and it’s hard not to see the parallel to contemporary media describing tennis great Serena Williams as a beast or an animal of one sort or another.

What Keene has given us in Counternarratives is fearless fiction: uninterested in transparent prose, dispensing with the unwritten insistence to be “contemporary” and “now,” breaking natural laws, blowing up large what conventional history has neglected or writ small, dumping the staid conventions of the short story.

Just as the counterpuncher — Muhammad Ali was among the greatest — sometimes defeats the puncher, the counternarrative sometimes becomes dominant. Recall the alternative Native American narrative launched by Dee Brown’s Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee, which set itself against the prevailing myth of John Wayne–type cowboys—atop white horses in their white hats — “civilizing” the frontier.

Keene’s collection is a book-length reminder that the inexplicable and the mysterious, the ancient and the unfamiliar — like recurring memories — persist.

Vincent Czyz is the author of Adrift in a Vanishing City. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, The Georgetown Review, Tin House online, Louisiana Literature, Southern Indiana Review

Tagged: Counternarratives, historical fiction, John Keene, New-Directions, short stories