Visual Arts Review: “Whistler’s Mother” — Up Close and Personal

With invention that suggests the work of Malevich and Mondrian, the composition is a play of rectangles.

Whistler’s Mother: Gray, Black, and White at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, through September 27.

James McNeill Whistler, “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 (Portrait of the Artist’s Mother).” Photo: Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

By Charles Giuliano

This summer the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown is hosting the blockbuster show Van Gogh and Nature.That and a sidebar exhibition, Whistler’s Mother: Grey, Black, and White (presented in collaboration with the Colby College Museum of Art and the Lunder Consortium for Whistler Studies) are generating capacity attendance for the museum.

Widely regarded as an icon of American art, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 (Portrait of the Artist’s Mother) was painted in London by James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) in 1871. It was first shown in the 104th Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art the following year and a number of times after that. Facing considerable debt, the artist reluctantly parted with the picture but was delighted that it was the first American painting acquired by the French government for the Louvre. The other is A Summer Night by Winslow Homer. Ironically, the painting initially received mixed reviews from critics.

Whistler’s masterpiece is now owned by Musee d’Orsay. In the 1930s Alfred Barr borrowed it for the Museum of Modern Art where 50,000 people viewed it. It then went on a tour of American museums. It then was elevated into pop culture archetype when it was used for a 1934 postage stamp honoring Mother’s Day. No doubt Whistler would have been skeptical about the adoration: “Art should be independent of all clap-trap—should…appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it…Take the picture of my mother…as an Arrangement in Grey and Black. Now that is what it is…what can or ought the public care about the identity of the portrait?” Whistler wrote in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, 1890.

James McNeill Whistler, “The Sleeper,” 1863. Black chalk on paper. Photo: Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

No stranger to controversy, Whistler fled Paris after he was cuckolded by Gustave Courbet. In London he sued the critic John Ruskin for libel. He won, but the incident ruined both men. The artist went overboard in creating The Peacock Room for Frederick Leyland, who refused to pay for the cost overruns.

In contrast to the turmoil in Whistler’s life and career, there is a compelling stillness in the portrait of his mother. It was sublime to sit in front of the painting, looking long and hard at its grisaille, minimalist, and geometric austerity. The composition is so well calibrated that the woman devolves into abstraction. From a modernist perspective it is inviting to see her as more of a shape — organic forms balancing an arrangement of rectangles — than as a palpable woman.

Apparently, she was a substitute when the model hired for the day didn’t show up. Initially, the artist posed Anna McNeill Whistler standing, but she couldn’t hold the pose. Having the elderly woman seated allowed her to be comfortable during the long sessions. The small foot stool became an accent in the composition.

In a letter to her sister about the experience, Anna stated “I was not as well then as I am now, but never distress Jemie [James] by complaints, so I stood bravely, two or three days, whenever he was in the mood for studying me as his pictures are studies, and I so interested stood as a statue! But realized it to be too great an effort, so my dear patient Artist who is gently patient as he is never wearying in his perseverance concluding to paint me sitting perfectly at my ease.”

Like so many of her era, Anna knew plenty of personal tragedy. She lost her husband, an engineer, and three of her children while the family lived in Russia. She returned to Lowell, MA where Whistler (famously) denied being born. In I863 she moved to London, living with her son and other children.

Studying the painting reveals little about her character or the relationship with her son. The picture is a study in composition rather than personal feeling. She sits rigidly erect wearing black the clothes of mourning. Like women of the period she has a white cap which drapes past her shoulder. Hands folded in her lap clutch a white handkerchief.

With invention that suggests the work of Malevich and Mondrian, the composition is a play of rectangles. Her head is not quite equidistant between two framed prints. By rendering this relationship a bit off balance Whistler creates visual tension.

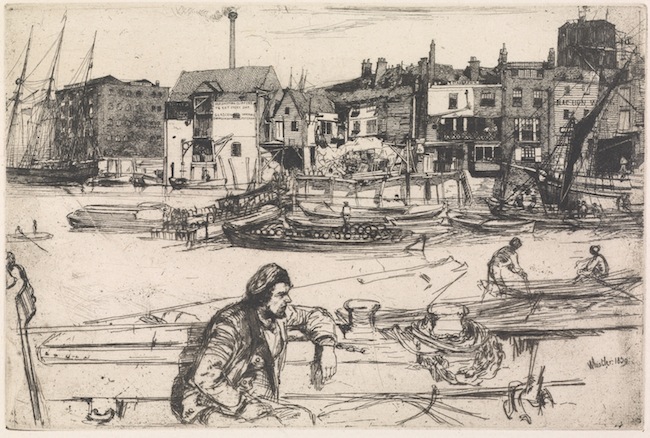

Black Lion Wharf, 1859, etching, The Lunder Collection Colby College Museum of Art . Photo: Courtesy of the The Clark Art Institute.

In the upper right corner of the painting we see just the black edged frame of another of his prints. Although just a sliver of that work it solves what artists describe as “the corner problem.”

On the left side of the painting is a broad vertical mass depicting black drapery. Only by direct observation is it possible fully to appreciate the intricate and subtle patterns of embroidered decoration. The richness and importance of this detail is entirely lost in reproduction.

Looking with the naked eye at the thin paint of the gray wall is surprising. The soft ambient light of the gallery makes the viewer aware of the texture of the canvas and encourages an appreciation of the flesh tones of the figure’s face and hands, which stand out in contrast to the black and gray. The value of masterpieces coming to our area is that it allows us to look closely and carefully at what we take for granted, to go beyond the reproductions. That’s why this rare opportunity to see Whistler’s Mother — up close and personal — is so precious.

The success of the painting led to a variation a year later Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2: Portrait of Thomas Carlyle. The portrait of the Scottish social critic, philosopher, and historian is in the collection of Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow.

The only other work in the gallery is Whistler’s print Black Lion Wharf (1859), one of his many etchings inspired by London’s waterfront. It is on loan from Colby College Museum of Art; a selection of Whistler prints are displayed in adjoining spaces.

Charles Giuliano, Founder/Publisher of www.berkshirefinearts.com, an art historian and former writer/critic/editor for Art New England, The Boston Herald Traveler, Boston After Dark, The Avatar, and The Patriot Ledger. He taught at New England School of Art at Suffolk University, Boston University, Salem State University, UMass Lowell and Clark University.