Book Review: “Young Skins” – The Precariousness of Even a Timid Existence

The events Colin Barrett renders in Young Skins have the texture of life, albeit the darker side, in that they puzzle and disturb and linger painfully.

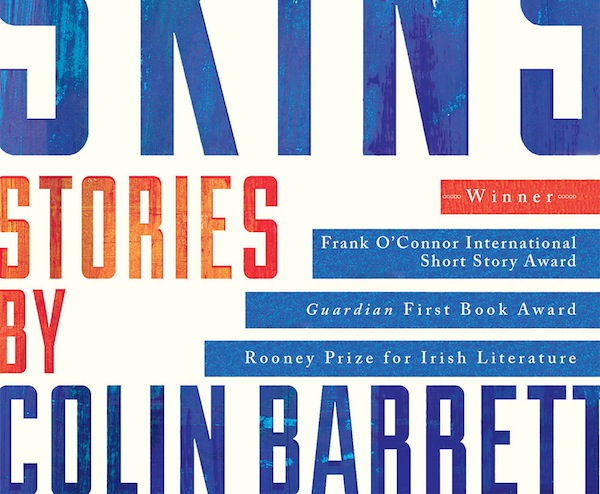

Young Skins by Colin Barrett. Black Cat, Grove Atlantic, 192 pages, paper, $15.

By Ted Kehoe

Colin Barrett is a young Irish writer who has already won a pile of awards for his collection Young Skins. These include the Guardian’s First Book Award, the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature, and the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. Colum McCann, Sam Lipsyte, and Colm Tóibín, among other literary heavies, blurbed this book, calling it “edgy,” “provocative,” and “stylistically adventurous.” These adjectives and accolades are deserved, yet they also suggest the book’s major problem. Still, they’re mostly beside the point. Barrett is a storyteller and his promise rests in this fact. The events he renders here have the texture of life, albeit the darker side, in that they puzzle and disturb and linger painfully.

There’s a lot to entice readers in this volume, or at least readers like me: humor; violence; that weird, syntactically inverted Celtic dialogue peppered with Gaelic; a never-ending parade of predators and outcasts, the maladjusted and underemployed. The characters drink too much. They grunt one-liners at each other. They make bad choices compulsively. They posture and dissemble. Their behavior seems mysterious even to themselves.

But Barrett is not the Irish Irvine Welsh. The peculiar vantage he appropriates to tell these stories saves this collection from being just another squalid chronicle of hapless folks for whom the Celtic Tiger might well be an animal act in a traveling circus for all the relevance it has had in their lives. In many of the stories in Young Skins the main character is the other guy: the sidekick, the victim, the passerby. They are caught up in the central drama, but mostly peripherally. This odd “Third Man” perspective also stifles, in an enervating way, the action of the stories until the characters fairly throb with anxiety and frustration and bewilderment. When Teddy follows Jenny and Sarah into the woods at the end of “Bait,” we know he’s not going to witness or take part in the sex act he hopes for. There’s an old Flannery O’Connor chestnut that makes its way around writers’ workshops: short story endings must be “surprising, yet inevitable.” And that’s what Barrett does best here. Of course the events surprise the reader because they surprise the characters, too.

I enjoyed many stories here. “Stand Your Skin” is the brutally sad yarn of Bat, who, after a serious head injury, just cannot seem to get his life started. We see him race his motorcycle down desolate country lanes, drink to dull his persistent headaches, and long faintly for a much-younger female co-worker he will never get and is only half-convinced he wants. Just how he came by his injury and what the circumstances of that injury mean for him, for all of us, is slowly revealed until the story culminates in a subtle shift into his mother’s point-of-view. We are left with her casual, devastating observations—I won’t spoil it. In “The Clancy Kid,” a national news story of a young child’s disappearance serves as backdrop to the standoff between deranged, leviathan Tug and the boy from the housing estate, slathered in war paint and armed with a scavenged aluminum rod—an eerie comic pantomime of a child-hero facing down his monster.

But the juggernaut here is the novella “Calm With Horses.” I’ve seen enough gangster movies to love a story where the henchman suddenly gets wise. Arm is a contemplative bruiser with an autistic child. His son’s disability is painted with very little sympathy and his various hoots and flails seem lunatic and alien (very nearly a misstep here, especially in a story told from the point-of-view of his father, but even this suggests Arm’s disorientation). “Arm,” or Douglas Armstrong, used to box for the county and now works as muscle for the local marijuana kingpin. Arm is put in a difficult situation when one of his boss’s dealers, after a night of hard partying, climbs into bed with the boss’s fourteen-year-old sister. But the pressure put on Arm doesn’t come from whom you’d think. Everything ends the way it began: exactly wrong.

Still, I have a complaint, and it is a big one. It goes back to all that high-powered acclaim: the prose is dreadfully overwritten. This is what many critics of literary fiction mean when they carp about the malicious influence MFA programs have on literature. To prove we are all well-mannered, dutiful acolytes of William Faulkner or Barry Hannah or Cormac McCarthy or whomever, we bright young things ratchet the lyricism up to a level of hilarity that fictional actions don’t warrant. The trick is to modulate lyricism, to be selective in application. Barrett’s language is turned up to eleven the whole time, most noticeably in verb choice: “‘More drinks. Go. Go,” declaimed Dympna sourly, jabbing Arm’s shoulder. Arm shed Lisa with a brusque duck and backstep and adjourned to the bar.” “Declaimed”? “Adjourned”? Does he mean “said” and “went”? The effect is cumulative and debilitating, exhausting.

Before long, I was glutted with words and prayed for a simple, clean, Marilynne Robinson sentence as respite. But the more insidious effect of this sort of riotous abuse of diction is that it ends in a dreary homogenization of literature—the Literary-Industrial Complex—so that this writer from Ireland sounds like this writer from France sounds like this writer from the States. And we all end up living between the pages of The New Yorker. Give me Barrett’s extensive cast of weirdos and lurkers and ne’er-do-well’s without all of this holy language. I only hope that he learns to streamline his prose so that his good stories reach us without interference.

“I have felt the wind of the wing of madness pass over me,” Charles Baudelaire writes in his journal. He has jotted a particular date—January 23rd, 1862— next to these words as if this fresh horror should be marked. Spirochetes of syphilis—an incurable disease at the time—had already burrowed into his brain and he looked forward, with dread, to a life very much unlike that which he had known before. A similar presentiment of catastrophe bedevils the characters in Young Skins. In these tales there’s a pervasive sense of dread and ominousness: we are reminded of the ubiquity of danger, the precariousness of even a timid existence. These are helpless characters stuck orbiting a world of Very Bad Things. But these stories promise something more complex and, I think, darker than simple memento mori. Barrett’s perspective insists that our lives can change in an instant and, as Baudelaire would learn, sometimes the wait to die can be long and awful.

Ted Kehoe was a teaching/writing fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His fiction has appeared in Ploughshares, Epoch, Southwest Review, Prairie Schooner, and Shock Totem. He won Prairie Schooner’s Bernice Slote Award for Best New Author. He teaches writing at Boston University.