Visual Arts Review: Duane Michals — Photography as Amazement

The photographer and the exhibition both make much of his outsider status and radical departure from the classic, reserved aesthetics of American art photography.

Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals, at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, through June 21.

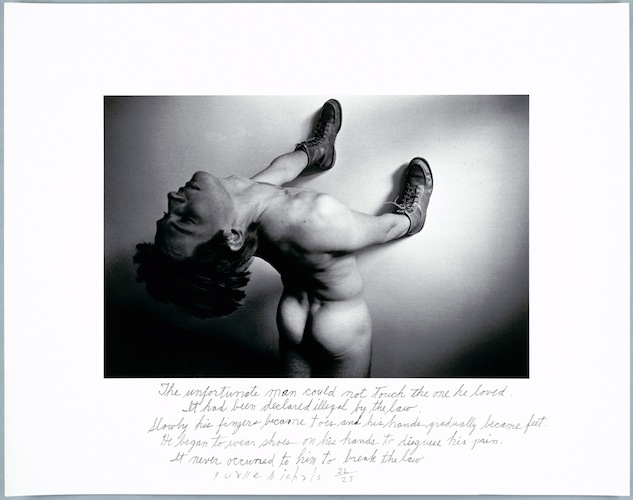

Duane Michals, “The Unfortunate Man,” Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text. Photo: Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.

By Peter Walsh

“If you are serious,” said photographer Duane Michals in an interview at the Peabody Essex Museum last month, “you have to be funny.” By that standard, Michals is very serious indeed.

Other Michals gems from a rollicking, frequently off-topic Peabody Essex performance, during which Michals played Groucho Marx to an interviewer (perhaps Margaret Dumont reincarnated?) included these: “I depend entirely on ideas. I never depend on my eyeballs (or any of my balls).” “Artists should never know what they are doing.” “[Joseph] Cornell was Andy Warhol strange. Professionally strange.” [Asked about what camera he uses]: “Would you ask [James] Joyce ‘what kind of typewriter do you use?’”

Michals began to penetrate public consciousness in the early 1970s, especially after the publication of his book Sequences and a solo exhibition of his work (Stories) at the Museum of Modern Art the same year. Michals’ carefully planned, serial photographs with captions or notations in his own, distinctively personal scrawl, suggesting diary entries, made an impression well outside the hothouse world of art photography. Usually small scale and black-and-white, the images were funny, ironic, disturbing, erotic, thought-provoking, and unexpected. The narratives were tenuous and odd but compelling. You typically arrived at the end of the sequence or caption with a small expletive, half laughter, half surprise. Content included love, death, sin, dreams, beautiful nudes, and disturbing episodes from childhood.

“A Young Man Going to Heaven” (1967), shows a sequence of a nude young man from behind as he climbs a narrow staircase. When he nears the landing at the top, his body is slowly absorbed into light. In “The Bogeyman” (1973), a small girl sits in a rocking chair, reading a book. She notices a hat and raincoat hanging ominously on a coat rack next to her and gets up to anxiously check that there is nothing really inside them. Reassured, she climbs back into her chair and falls asleep. Then the coat sprouts legs, jumps down from its rack, and carries her off.

Especially in this early work, Michael’s use of beautiful young nude bodies is particularly striking. The images are highly erotic without quite being pornographic, both stark (and in stark settings) and sensuous. The nudity rarely has much to do with the story line but is always perfectly suited to its narrative.

Michals’ nude models have a certain unselfconscious innocence. They are often used as a symbol for the fragility and transience of all things human, especially human beauty, and they often face a looming doom. In the long sequence “The Bewitched Bee” (1986), a retelling of the myth of Diana and Actaeon in which Diana is mysteriously and conspicuously missing, a nude young man sprouts antlers, wanders into the woods “looking for love.” Eventually, he “drowns in a sea of leaves.”

Michals’ portraits of famous people, less familiar than the sequences, play a notable role in this exhibition. They are not the usual “celebrity photographs” that have become so familiar in contemporary culture. For the most part, the subjects are people Michals particularly admires or who have played a role in his life of work.

Several photographs of the French surrealist painter René Magritte, made during a week’s visit in 1965, play on themes from Magritte’s work, especially his iconic bowler hat. They are images of an artist with whom Michals’ clearly has a deep affinity. “In your lifetime you may meet three people who will free you,” Michals says. “You may not even meet them, you may read about them, but whatever — anything that frees you — and Magritte did it for me.”

What exactly Michals needed to be freed from is not entirely clear. Perhaps it was taking the plunge into fine art. The photographer and the exhibition both make much of his outsider status and radical departure from the classic, reserved aesthetics of American art photography.

Michals repeatedly describes his photographic skills as “completely self-taught,” although in the late 1950s he studied at the Parsons School of Design, intending to become a graphic designer. After military service, he moved to New York with the aim of working in publishing. He claims he discovered an interest in photography during a 1958 trip to the USSR, where he photographed children, precursors to the haunted adolescents in his mature work.

Later, Michals worked as a commercial photographer for the glossy and glamorous picture magazines of the 1960s, including Esquire, Mademoiselle, and Vogue. His “revolutionary” use of photo sequences and captions may well have a source in this Golden Age of editorial photography.

By the 1960s, readers of the large-format, glossy photo-journalism magazines like Life and Look had become used to the idea that photographers used automatic shutters that captured moving figures in close sequences. These publications published black-and-white photo sequences from a single roll of film, with captions explaining the progression of an event, often a comic one, as it unfolded. In doing so, they established an ironic, playful form of photographic narrative not dissimilar to Michals’.

In adapting commercial graphic techniques and aesthetics to a fine art context, Michals followed in the same footsteps as his friend Andy Warhol had done a few years earlier. Warhol, like Michals, came from a modest, working-class background in the Pittsburgh area, also used photographic images in sequence, altering them with commercial graphic arts techniques like silk screen. The “professionally strange” Warhol was, Michals says, “a real fake,” a term apparently of affection. Both artists played with the ironic, ambiguous shotgun marriage of image and reality that marked photo-journalism and advertising during the Mad Men era.

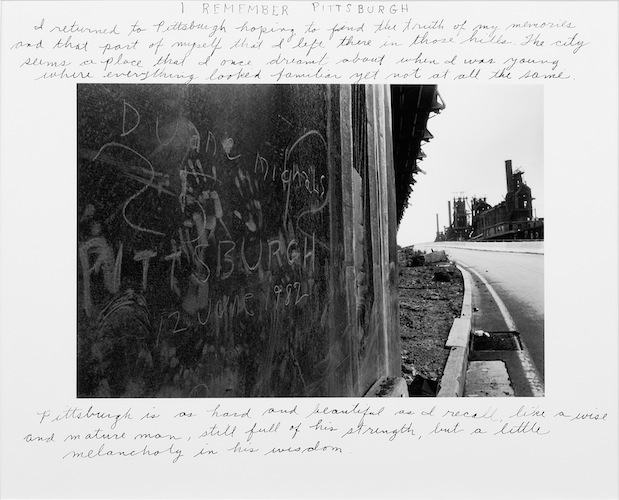

Duane Michals, “I Remember Pittsburgh, 1982. Photo: Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.

The exhibition at the Peabody Essex places a mild emphasis on Michals’ later work, much of which looks back on his working class childhood in Pittsburgh. This slant has apparently caused some observers to call the exhibition “sentimental.” In fact, Michals view of his growing up is tart and distancing; his childhood memories are full of conflict and resentment. In “The House/ Once Called Home” (2002), Michals writes “This abandoned wooden box is the cabinet where my family’s curiosities are stored.”

Twenty years earlier, in “Six Views of the Cathedral of Learning in the Manner of Hiroshige” (1982), Michals photographs an iconic Pittsburgh landmark distanced by reference to sequences created by the celebrated Japanese printmaker. After decades in New York City and a life utterly unlike his father’s, Michals has never quite managed to leave Pittsburgh behind.

The Peabody Essex installation is up to the museum’s usual high standards: clear, graceful, and well thought out. Instead of cramming the show into a small graphic arts gallery, Michals’ intimately scaled images are given plenty of breathing space in a major special exhibition gallery.

“Photography is about amazement,” Michals proclaimed in that March interview. The presentation at the Peabody Essex certainly makes that point.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

[…] – Photography as Amazement – The Arts Fuse. [online] The Arts Fuse. Available at: <https://artsfuse.org/125804/fuse-visual-arts-review-duane-michals-photography-as-amazement/> [Accessed 4 March […]