Visual Arts Review: Planes, Trains, and Automobiles at the MFA — The Beauty of Speed

Planes, Trains, and Automobiles at the MFA is a delightful exhibition dedicated to vehicular speed, mobility, style, and joy.

Planes, Trains, and Automobiles: Selections from the Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA through May 10, 2015.

1934 LaSalle design model. Designed by: Harley J. Earl. Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By Mark Favermann

Life sped up during the middle of the 20th Century. It also gained a sense of style. This appealing exhibition of collectors Fred and Jean Sharf’s wonderful collection of a variety of transportation art and objects proves that acceleration and aesthetics make an exhilarating combo.

From an early age, most of us treasure model cars, airplanes and trains. It may have something to do with fantasy, a sense of imagined Lilliputian power or just a love of beautifully made scale models that we can hold in our hands. These may be outmoded generalizations, but most boys adore model trains, cars, trucks and airplanes, while a large majority of girls start out liking doll houses and everything that goes into and outside of them. There is a certain magic to miniaturization.

Miniatures make us seem to feel more adult, perhaps more in control. We are innately attracted to replicas of functional objects. Through them, we receive various levels of pleasure. Add to this the fact that exhibitions in a major museum which display the smaller objects are often among the most appealing. The intimate scale embraces us more fully. This is very much the case with the splendid, transportation-themed show “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles,” which illustrates the period of great expansion in all forms of travel.

Over 80 objects are on display. Here popular culture marries industrial design, art and technology. The exhibition includes sketches, renderings, posters, models, sculptures, clothing, and a few toys from the mid-twentieth century. Seeing these pieces encourages visitors to dream about aerodynamic speed, power and flight, to sense how quickly Americans experienced radical changes in transportation. These breakthroughs happened in commercial aviation, vehicular travel, and train refinement because of the evolution of technology, which pushed the creation of more highways and airports.

The various works included show the ways designers responded to the demands of manufacturers, marketers, and engineers, with particular emphasis on how they found ways to get people from one place to another in exquisitely dramatic style. There are famous designer names here as well as works by anonymous artists. All capture a time when travel had more romance than it does today.

Deutsche Lufthansa Ju 52 model. Photo: Mark Wallison, courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This exhibit includes models that were used in wind tunnels, to test color schemes, to serve as prototypes, to help designers decide about shapes, or to convince companies to buy a product. Some of them were given away as trophies or were set on executives’ desks. Others were bait to lure customers into travel agencies. There are even a few toys.

Automotive styling officially began in 1927 when General Motors president Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. hired Harley J. Earl (1893 –1969) to add so-called emotional or eye appeal to car design. Up until then, car manufacturers had paid little attention to aesthetics except in higher end vehicles. Before long, car design was a dominant force in the manufacture and sales of American automobiles.

GM’s Public Relations department dramatically declared in 1958: “This dynamic obsolescence caused by the annual model change is the life-blood of the auto industry and a key factor in the national economy.” The MFA’s display of automotive art and design loosely represents the evolution of car styling in the United States from the ’20s to the early ’70s.

Though the Wright Brothers made their first flight in 1903, commercial aviation did not really begin until the ’20s. The period during and after World War I brought enormous improvements to airplane design. By the mid-’30s, regular flights crisscrossed the United States. At the time, it was a luxury activity limited to the wealthy.

World War II stimulated huge technological advances and the beginning of a real democratization of flight. The design of airplanes is more closely tied to function and physics than is the contours of cars or trains. Small changes had big effects on airplane performance and safety. These constraints meant that designers had less creative freedom than their automotive or train counterparts.

Even so, planes from each decade seem to fit with other vehicular designs of their era. This is because plane designers saw with a “period eye”; their aesthetic choices and sense of aerodynamics reflected the visual configurations of the day. They couldn’t help but mirror ‘the look’ of the era.

At the beginning of the 20th century, American railways were at the top of their game. Because ridership and freight usage were high, there was demand for manufacturers to develop faster and more powerful locomotives.

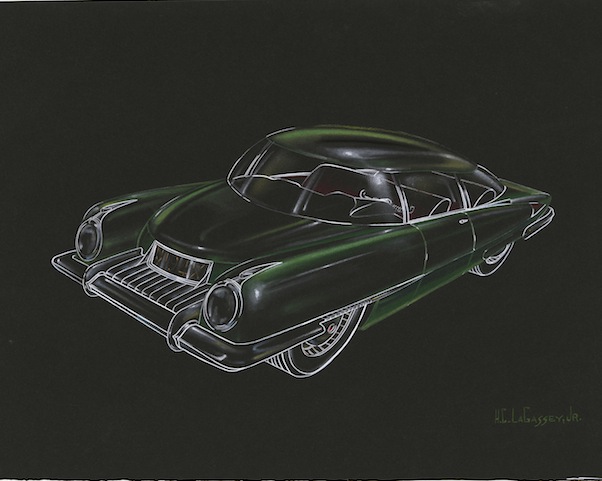

Design for a two‑door car. Homer LaGassey, colored crayon, watercolor. Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Eventually, competition from automobiles and airplanes suggested that trains would no longer play a dominant role in the future. Sensing the threat, in the ’30s the railroads embraced design. Traditionally, locomotives had always worn their mechanical elements on their outside.

Pioneer industrial designer Raymond Loewy (1893 – 1986) helped the Pennsylvania Railroad dress up its dowdy old railcars in stylish new attire. Other railroads tried this as well. His approach was to clothe trains in an outer casing that made them seem to be moving fast while standing still. However, by the ’60s, planes and cars had won the transportation competition: the railroads entered a long and slow decline.

Among the highlights of the show are an impressive range of model planes, including futuristic prototypes such as a YB-35 Flying Wing bomber that later led to Stealth Bombers, a 1934 Burlington Zephyr model train, and a 1936 Airomobile prototype. Other charmers: there’s a wonderful wooden and metal 1922 car model, a brilliantly painted truck by Viktor Schreckengost (1906 –2008), a tapestry commemorating Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic, a child’s transportation-themed kimono, and a rendering of a snazzy sedan of tomorrow.

Because this is not an area of scholarship at the MFA, the curators have asked the public to enlighten the museum about various aspects — from the puzzling to the mundane — of exhibition’s objects. This is a different and refreshing form of museum interactivity.

An urban designer, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox since 2002.