Visual Arts Review: “9 Artists” at MIT — Alienation, Resignation, and Despair Made Stimulating

After repeated visits (and you will need several to even scratch this dense content), 9 Artists begins to hang together in satisfying ways.

9 Artists at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, MIT, Cambridge, MA, through July 13.

Liam Gillick, The State Itself Becomes A Super Whatnot, 2008. Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York

By Peter Walsh

The exhibition 9 Artists, organized by the Walker Art Center of Minneapolis and now on view at MIT’s List Center, features eight artists of mixed nationalities. The numerical discrepancy has drawn notice “especially at a place like MIT,” said the List’s Assistant Curator Alise Uptis, who collaborated with the Walker on the MIT installation. The missing artist has become both a symbol of the show and a legend, the third man or woman of a mystery yarn.

As with most large loan shows, the Walker Center organizers chose the title 9 Artists long before they selected the artists themselves. The exhibition’s organizer, Walker curator Bartholomew Ryan, explained that when the exhibition catalogue came back from the printer and he counted the names on the cover, he realized that they had never quite filled the original quota. Oops. But into that accidental nothingness quickly flowed deep rivers of existential meaning.

One of the eight artists, Uptis claimed, threatened to withdraw if a ninth artist joined the now-established eight. Ryan observed, correctly, the show would have seemed “very ‘60s” if it had actually been about nine artists. Certainly the disjunction has a post-post-modern ring to it, a negativity fitting to an exhibition with the theme of not having a theme.

This is a project that sets out to be about “neither nor,” that continuously and exactingly questions its own purpose. It writes the equivalent of a doctoral thesis on what it means to not be what it is not about. It keeps insisting “we can’t talk about that” and goes on about it anyway. At considerable length.

The exhibition biography for artist Natascha Sadr Haghighian starts out flatly stating that the artist “abjures biography altogether,” then adds another 101 words of non-biography, noting that Haghighian (who is Iranian and lives in Berlin) sees “the artist résumé as a globally pervasive mode of regulating individuals according to conventional markers of identity such as age, nationality, education, and institutional affiliations…”

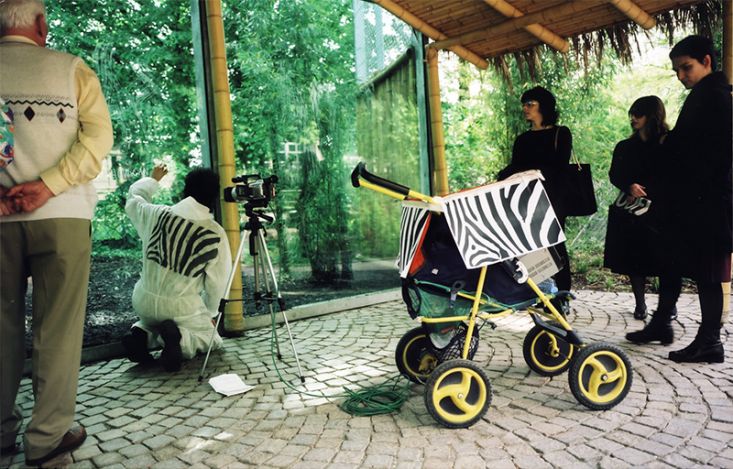

Haghighian’s thirteen minute video in the show, present but not yet active, is about “her choice to forego an invitation to participate in Manifesta and to instead invite the European art biennial’s three curators to visit the Frankfurt Zoo” in “an attempt to take part in an exhibition without displaying anything, but instead by ‘diffusing’ into the show through a shared experience with the curators.”

Elsewhere, in a video developed with the Swedish-Iraqi-Brooklyn artist Marie Karlberg, Bjarne Melgaard (gay Australian-Norwegian-New Yorker), and Leo Bersani (gay literary theorist and emeritus professor of French at Berkeley) discuss, for some ninety minutes and in graphic detail, why you really can’t discuss gay liberation any more.

Hito Steyerl, How Not To Be Seen. A Fucking Didactic Educational .Mov File, 2013>\, HD video projection. Courtesy the artist and Wilfried Lentz, Rotterdam.

Right now you may be thinking that this show, with its gregarious angst, affirming nihilism, and exuberant anomie, has a lot of art world inside baseball in it. You’d be right. At first blush, in fact, it can seem pretty opaque.

Squeezed into about half the space 9 Artists had in Minneapolis, the List installation blurs the lines between participants. Tropical bird calls from Haghighian’s zoo bleed into Renzo Martens’ taped lecture on his Institute for Creative Activities. Liam Gillick’s billboard-sized broadsides on the failure of utopian ideals fill whole walls in the gallery and spill into the spaces beyond.

Most of the artists have more than one piece in the exhibition and a single piece can have many parts. Dan Vo’s IMUUR2 incorporates several hundred objects from an eclectic collection assembled by the late painter Martin Wong and his mother, Florence — antiques, artifacts, nicknacks, cookie jars, souvenirs, Asian vases and statuary, manuscript pages, and paintings by Wong himself. A casual visitor might be excused if he thinks there are five artists in the show, or two, or twenty.

Like so much of contemporary art, most of the works center on videos. Several of these are epic. Yeal Bartana’s and Europe will Be Stunned documents, in the style of 1930s propaganda film, a call for 3 million Jews to return, not to Israel but Poland. The elaborately constructed fictional scenario includes an address in a Polish stadium, a social movement with uniforms, slogans, symbols, and a manifesto in several languages, the construction of a kibbutz from scratch on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto, and an entire public funeral, verbatim, political speeches and all.

If part of the show’s point is to highlight the chaotic, indecipherable nature of contemporary life, it succeeds very well. On the other hand, after repeated visits (and you will need several to even scratch this dense content), the show begins to hang together in satisfying ways.

Like the clicks, pings, and sneezes in a John Cage composition, the apparently random juxtapositions not only make a kind of sense after awhile but come to seem more and more interesting. For one thing, the selection of artists is less incoherent than the show’s curators like to pretend.

Although their ethnic origins are, indeed, very diverse, most of these artists have a connection to one or more established art capitals, especially New York and Berlin, both centers of socially-engaged art for generations. The work draws on many of the same sources, including conceptual art, “relational art” (first applied to an exhibition that included Gillick’s work), Post-Marxist leftist economics, and (I suspect) the neither-nor politics of George Orwell.

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, present but not yet active, 2002, Video. Courtesy the artist and Johann König Gallery, Berlin

The pieces on view overflow with ideas and more ideas, with identity politics, political theory and economics, with art history and its benign, anti-historic double. Never before has alienation, resignation, and despair seemed so stimulating.

In two splendid, if rather poorly attended, artist talks, Gillick and Martins extemporized on the themes in their work.

Gillick was gloomy on the state of a “rampant art market” and the “problem of trying to deal with contemporary art only using philosophic or economic terminologies.” He bemoaned the “inability of art to produce anything real” but his pursuit of his ideals seemed relentless and his delivery remained energetic and engaged. Surely, you thought, artists this full of provocative and attractive ideas would eventually wriggle out of whatever dead end they had backed themselves into.

In his talk, Dutch artist Renzo Martens showed parts of his famous videos, shot in some of the most dismal parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Showing conditions on a former Unilever plantation where Martens established his Institute for Human Activities (IHA), the film is heartbreaking, its protagonists crushed by a form of free market capitalism that seems much worse than slavery. He described his efforts to use art and trendy economic theory to make a difference, any kind of difference, to lives that seem tragically out of reach.

At one point in this riveting narrative, he looked out into the dark, nearly empty auditorium and asked something along the lines of “are you still awake?” Well, yes. Yes we are.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.