Visual Arts Review: “Raven’s Many Gifts” at PEM — When Cultures Collide

How much can a “native” artist adopt from Western modernism before his art loses its tribal identity and, along with it, its appeal to an outside market?

Raven’s Many Gifts: Native Art of the Northwest Coast , at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, through May 31, 2015.

By Peter Walsh

What happens to art when two sophisticated cultures collide? An installation at the Peabody Essex Museum suggests some fascinating answers. Then it poses a few more unanswered questions.

On the fringes of several empires—Spanish, Russian, English, and, eventually, American— the damp evergreen forests and rugged coastlines of the northwest coast of North America were too far from the centers of colonial power to attract much attention. What interested outsiders most was the fur trade. That enterprise quickly made the locals rich.

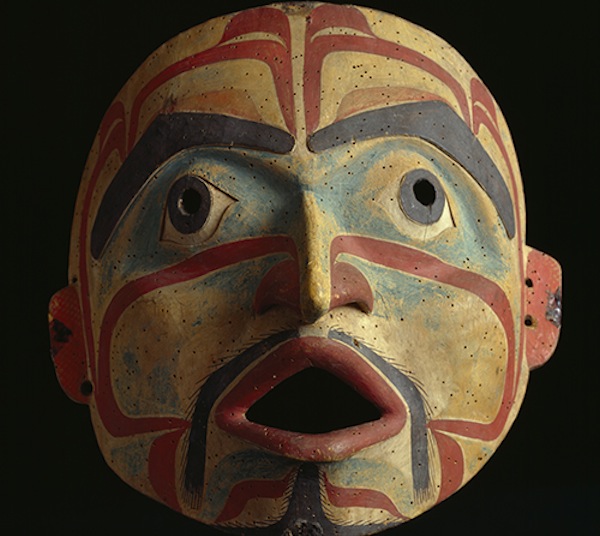

Not that they were badly off before. A pleasant climate, abundant salmon and whales, and plentiful timber gave the coastal tribes a comfortable lifestyle long before Europeans appeared. Famous for totem poles and elaborately carved and painted houses, the Northwest Indians created an advanced visual culture. Their carved wooden masks, ceremonial rattles, sophisticated chilkat blankets, decorated pipes, and costly “coppers” used a distinctive, semi-abstract style called “formlines” to represent humans, animals, ancestors, supernatural beings, and the narratives of myths.

The art became the central ingredient in the famous Potlatch, an aristocratic celebration of births, deaths, weddings, and other major family milestones. Part conspicuous consumption, part elite competition, part ritual, part redistribution, the Potlatch shifted riches from the top tiers of society to the lower orders. Noble families gave away quantities of costly blankets and other art works and burned or smashed others, including the coppers that were said to be worth more than a slave.

The “Native Art” of the Peabody’s Raven’s Many Gifts: Native Art of the Northwest Coast is a bit of a misnomer. The oldest pieces in the show, from the mid 19th-century, are already hybrids, blending local traditions with the influence and market interests of outsiders. In this show, the older objects are small, the sort of thing sailors and traders would have brought home as souvenirs. The exhibition explains that much of the art on view was made for sale, not destined for the fires of the Potlatch. To supply this new export market, Indian artists adapted new materials, including carved stone, and new forms.

The signature piece of the show, an intricately carved wooden mid 19th-century rattle from the Haida tribe, represents “Raven” from the exhibition’s title—a clever trickster and Promethean figure from Indian mythology. A human figure lies on the raven’s back, his tongue joined with another bird he faces. This is as “classic” as the installation gets.

The native northwest culture reached its peak in the late 19th century, just as the German-American anthropologist Franz Boas completed several famous studies of the Northwest tribes. By the mid 20th-century, under pressure from missionaries and governments to assimilate and abandon traditions, including the Potlatch, the native culture was moribund. Then, in the second half of the century, a revival began. This forms the counterbalance of the show, which contrasts 19th-century pieces with 20th-century or contemporary works.

Near the raven rattle is an Eagle Salmon Blanket, traditional in form, but it uses ultrasuede as well as wool and mother of pearl. It is the work of Dan Yeomans (born 1957) and Trace Yeomans, both of Haida ancestry.

On a nearby wall is Nicholas Galanin’s two-part video, Tsu Heidei Shugaxtutaan (“We will again open this container of wisdom that has been left in our care”).

Galanin is a member of the Tlingit tribe. His video is shot in black and white, perhaps in imitation of Boas’s famous early films of Northwest coast ceremonies. The first part of Tsu Heidei Shugaxtutaan features hip-hop dancer David “Elsewhere” Bernal performing to a traditional Northwest chant. The second part shows Tlingit dancer Dan Littlefield in full regalia, including a mask, performing a traditional raven dance to a techno-electronic beat. Bernal easily adapts his loose-limbed style to the chant, making Part 1 more convincing than Part 2, which seems self-conscious and a bit forced, asserting its point about worlds in collision with a heavy hand. Still, of all the contemporary artists in the show, Galanin asks some of the most cogent questions.

Galanin’s 2006 piece, Bear Mask Vo. 9 (from the “What Have We Become?” series), poses one of these. Traditional in form and paired with a 19th-century Haida mask, the artist’s work is made out of layers of laser-cut paper. The colorless mask blurs, as if seen through fog or smoke—an image of uncertainty. Richard Hunt and John Livingston’s Door (1984) also resonates with ambiguity: a wooden door beautifully carved and painted in a classic formline design but with ordinary brass-plated hardware. It pays homage to the monumental carved house fronts of the 19th century, yet it is a modern facsimile. Does it reduce a great tradition to a mere decorative motif?

In nearly every case, the 19th- and early 20th-century adaptations in the show seem effortless and confident, their creators easily able to adapt outside pressures into new art forms. When missionaries persuaded the Indians to abandon their traditional totem tattoos, Northwest artists adapted the motifs to beautifully conceived silver bracelets. Both the materials and concept are alien, yet the result seems resolved and “native.”

One of the most delightful adaptations in the show, a Haida “ship panel pipe,” made around 1842 for sale to a visiting sailor, shows a fantastic animal (probably adapted from a ship’s figurehead), houses, and strange vegetation that might be trees or native tobacco plants. Here the collision of cultures has an unexpected and delightful result; the Haida artist has completely absorbed the alien influences into a unified work.

In contrast, the late 20th- and 21st-century pieces—sophisticated, worldly, and technically accomplished—seem to float on the threshold of the modern commercial art world. How to adapt for gallery sale styles created for an utterly different conception of art? How much can a “native” artist adopt from Western modernism before his art loses its tribal identity and, along with it, its appeal to an outside market? Can a native artist move completely beyond tradition and still be native?

All this is complicated by the fact that the native Northwest Coast idea of art is very different from a contemporary American one. Even the concept of an art museum or gallery was not part of that original context. Totem poles and painted houses were supposed to naturally decay back into the forest and other art works were mostly meant to be consumed and replaced by new ones. It was only after contact with Europeans that the Indians began to use more permanent materials, including stone and silver, that fit more closely European assumptions about the immortality of art.

A series of serigraph prints from the 1960s, early in the Northwest cultural revival, are a case in point. The medium is completely modern, one taken up by many mid-century American gallery artists, Andy Warhol among them, but here the forms and content are traditional. Here they seem to be more compromise than a venture into new territory. Adapted for those who already have an appreciation for Northwest Coast imagery and mythology, these prints seem unable to make the leaps made by work created by the artists’ ancestors, who were less self-consciously aware of the tastes of their collectors and apparently unburdened by the weight of their own heritage.

The play of tensions and solutions make for a rich and thought-provoking exhibition, though visitors unfamiliar with Northwest Coast traditions may need more than one visit to absorb it all. There’s plenty of time, though. This longer-term installation will be on view through the end of May 2015.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

Tagged: Native Art of the Northwest Coast, Peabody Essex Museum