Book Review: The “Lightweight” Gallows Humor of Jean Echenoz

Eschewing harrowing realistic description, Jean Echenoz adopts a jocular sardonic approach to the most gruesome battlefield realities.

1914, by Jean Echenoz. Translated from the French by Linda Coverdale, The New Press, 118 pp., $14.95.

By John Taylor

Ever since his first novel, Le Méridien de Greenwich (1979), Jean Echenoz (b. 1947) has shown himself to be a novelist with a style. This quality is rarer than one might think. Subtle, droll, melodious, oddly distant and oblique, Echenoz’s tone propels his stories forward as surely as the recounted events do. He has won two important prizes in France: the Médicis Prize in 1983 for Cherokee (translated with the same title at the University of Nebraska Press) and the Goncourt Prize in 1999 for Je m’en vais (translated as I’m Gone at the New Press). Several of his novels, like Piano (2002) and Ravel (2006), weave musical themes or at least allusions to music into the plot. These and most of his other books are available in English.

But he also has a few—just a few—detractors among French critics. They find his style, that is, his distinctive tone, to be too “léger,” too “light” or “lightweight.” They argue, implicitly or explicitly, that he has not delved deeply enough into his subject matter and that, especially, his emotional commitment to his tale is somehow insufficient. Literary values and critical presuppositions are at stake here.

It is true that distancing effects in Echenoz’s books tend to heighten the reader’s awareness that the story is fictional. For this reason, one enjoys a novel by Echenoz at one remove without necessarily being engrossed in it. And it is true that these same distancing effects keep the emotional temperature at a lower degree than what one had expected, given the potential intensity of the archetypal scene—and the author delights in sporting with the archetypal scenes of popular fiction and other literary genres. Can it be said that Echenoz, through his bemused approach, is chiding us about those same expectations which, after all, may represent no more than lazy intellectual habits?

In any event, his “lightweight” novels offer no light reading. On the contrary, something weighty and unnamed is usually kept at bay. It lurks not far away. To pun with another sense of our English word “light,” I see this ponderous potential menace just beyond Echenoz’s pages as something “dark”—such as death, to the inevitability of which we, the living, must adapt as best we can.

Another way of considering this ambivalence or paradox at the heart of our reading experience of Echenoz’s prose is to think of a smooth opaque surface that implies a “depth” that is really down there, though we cannot peer into it in any detail. An iced-over pond provides an apt metaphor. The “depth” of the pond becomes all the more hauntingly present once we have grasped how the surface conceals it. Actually, Echenoz often gives hints, like ice holes. And now and then he purposely makes the icy surface crackle.

Linda Coverdale captures this unique style in 1914, Echenoz’s latest novel, the French original of which the Éditions de Minuit had the elegance to publish in 2012 and not among the plethora of books about the First World War that have been issued in France this year.

Set in Vendée at the onset of the war, the novel tells the story of two brothers, Charles and Anthime, and their common love for Blanche, who, by the way, is pregnant (out of wedlock). Her predicament, which she does not see as one, however, is theoretically rather complicated in that she is the heiress to the local shoe factory. The general manager of the factory is Charles, and the accountant, Anthime.

Who is the future father? For quite a while, the reader will not be entirely sure. The odds greatly favor Charles, the more handsome, talented, and self-confident of the two siblings. A few details nonetheless raise doubts and point to the poorer, less gifted Anthime. Above all, his love for Blanche seems so sincere and disinterested.

This playful, low-key kind of “suspense,” which is typical of Echenoz’s writing, continues at an emotionally subdued pace despite a looming dramatic event: before the child’s birth, both Charles and Anthime must march out of town to fight on the French front. Off they go, in turn passing by Blanche:

As he’d expected, Anthime had first seen Blanche smile proudly at Charles’s martial bearing and then, as he drew abreast of her in turn, he was not a little surprised when she gave him a different kind of smile, more serious and even, he felt, a trifle more emotional, pronounced, sustained, well who knows, exactly. He had neither seen nor tried to see how Charles—with his back to him, in any case—had reacted to her smile but he, Anthime, had responded only with a look, the shortest and longest one possible, forcing himself to invest it with the least amount of expression while at the same time suggesting the maximum: a novel approach, doubly paradoxical this time and which, as he strove to keep in step, was no small undertaking.

Adding to an atmosphere that is delicately amusing despite the hovering clouds of war is, of course, the juxtaposition of the rare first name, Anthime, and the common first name, Charles, to which can be added the somewhat comical names of three other characters, all fishing buddies of Anthime’s: Arcenel (a saddler), Bossis (a butcher’s apprentice), and Padioleau (a slaughterhouse knacker). They also head for the front. Moreover, although I have already announced that Anthime and Charles are brothers, this news is actually given on page 60. From the onset, the narrative is askew and gently puzzling.

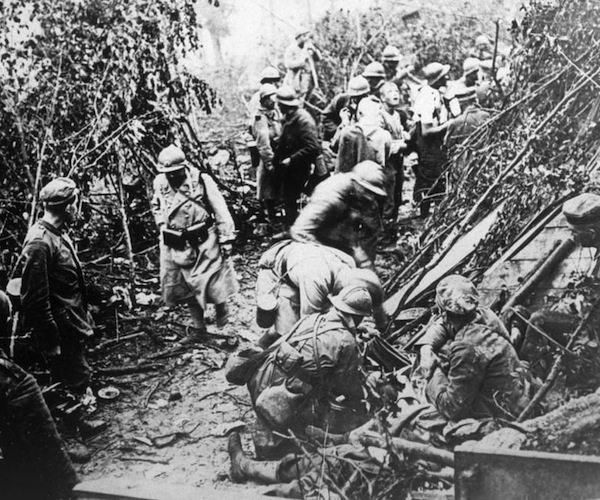

Deft effects like these are countless. They forbid me from relating the story any further, lest I disclose how the plot unfolds and concludes. Suffice it to say that the brothers, as well as Arcenel, Bossis, and Padioleau, reach the front, that they and everyone else in France imagines a quick end to the tension with Germany, that this wishful thinking founders pathetically, that the fighting begins and becomes increasingly savage (trench warfare, shelling, bayonets, mustard gas), that one of the brothers gets assigned, thanks to Blanche’s connections, to the aerial photography crew. . . .

Will the brothers die? Will the baby be born and one day be cradled in his or her father’s arms? “Let’s not get carried away,” as the narrator—if I remember correctly— cautions at one point. Or, to quote another of his asides about the very story he is narrating (for this novel about the First World War is also about writing a novel about the First World War):

All this has been described a thousand times, so perhaps it’s not worthwhile to linger any longer over that sordid, stinking opera. And perhaps there’s not much point either in comparing the war to an opera, especially since no one cares a lot about opera, even if war is operatically grandiose, exaggerated, excessive, full of longueurs, makes a great deal of noise and is often, in the end, rather boring.

With ease, Echenoz takes off in a different literary direction. Eschewing harrowing realistic description, or, more precisely, evoking only in passing what is harrowing instead of describing it meticulously, he adopts a jocular sardonic approach to the most gruesome battlefield realities. Let me reveal just one additional element of the plot as an example of this tone:

[A] tardy piece of shrapnel showed up, from who knows where and one wonders how, as clipped as a postscript: an iron fragment shaped like a polished Neolithic ax, smoking hot, the size of a man’s hand, fully as sharp as a large shard of glass. Without even a glance at the others, as if it were settling a personal score, it sped directly toward Anthime as he was getting to his feet and, willy-nilly, lopped off his right arm clean as a whistle, just below the shoulder.

The shrapnel mentioned here is representative of the numerous historically specific military objects that crop up in the story. Echenoz has done his research well and we know this. These props stand out in ways which, once again, nudge the reader into observing as if anew a character’s plight more than immediately identifying with it. Let me cite a second additional passage as an illustration, even if it half-unveils an especially moving part of the narrative:

Beyond a bend, the fourth path broadened into a grassy clearing carpeted with cool light filtered by the freshly unfurling leaves, a delicate tableau. But on a corner of this carpet were three men on horseback, in tight uniforms of horizon blue, back straight, mustaches brushed, expressions severe, aiming at Arcenel three examples of the 1892 8-millimeter French service revolver while ordering him to present his service record booklet, but he hadn’t brought that along with him either. They asked him for his serial number and enlisted assignments, which he recited by heart—section, company, battalion, regiment, brigade—while opting to meet the gentle, attentive, and deep gaze of the horses rather than the eyes of the gendarmes. Who did not bother asking him what he was doing there: they tied his hands behind his back and ordered him to follow, on foot, the equestrian detachment.

The cumulative effect of Echenoz’s “lightweight” kind of gallows humor is impressive. By giving timeworn images an unexpected tonal frame, the novelist revitalizes our numbed perceptions of the all too human horror of the First World War and the millions of individuals who were caught up in it. In 1914 as in 1914-1918, most of these men are minced by the war machine. A few miraculously survive, maimed and mentally devastated. They had to adapt to the present when they were forced to fight; now they have to adapt to the future as best they can. Anthime, for instance, subsequently invents the “Pertinax moccasin”—look up the historical allusion!—at the shoe factory because he can no longer tie shoelaces. (Oh, I’m giving away more of the plot!) It’s quite a tour de force when distancing effects bring us so much closer to the real men these engaging hapless fellows must have been.

John Taylor has just published a translation of José-Flore Tappy’s collected poems, Sheds (Bitter Oleander Press). His recent translations include works by Philippe Jaccottet, Jacques Dupin, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, and Louis Calaferte. He is the author of the three-volume essay collection, Paths to Contemporary French Literature (Transaction, 2004, 2007, 2011). His most recent personal book is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012). In 2013, he won the Raiziss-de Palchi fellowship from the Academy of American Poets for this project to translate the work of the Italian poet Lorenzo Calogero.

Tagged: 1914, french fiction, Jean Echenoz, Linda Coverdale