Visual Arts Review: Designing the California State of Mind

California has long been the home of fads, trends, new styles and the next new thing. It is where cool was and is created.

An elegant Buck Rogersesque bright red Ice Gun (Opco Company) from 1935. Photo: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

California Design, 1930-1965: Living in a Modern Way, at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, through July 6, 2014

By Mark Favermann

Upon entering the Peabody Essex Museum, the visitor is greeted by a car—a spectacular turquoise Studebaker Avanti. This iconic vehicle was designed by industrial designer Raymond Lowey in the early 1960s. It was created in an intense design charrette or workshop in Palm Springs, California. This wonderful machine is at once sleek, aerodynamic, and an advertisement for minimal embellishment. It was a strong aesthetic reaction to the chrome and useless gewgaws that had previously adorned the American cars of the late fifties.

Distinctively low-slung, Loewy’s concept is wedge-shaped in profile, with Coke bottle contour shaped fenders, flush-mounted bumpers, and a grilleless nose. Uniquely, the front sits more than an inch lower than the tail. With its Fiberglas body and overall form, the car epitomizes the idea of California cool.

California has long been the home of fads, trends, new styles and the next new thing. It is where cool was and is created. This has been especially centered both in the consumer product–based Los Angeles and the cyber-oriented Silicon Valley.

Throughout most of the 20th century, what was contemporary could have been defined as created in California. It has been said that California may be a state of mind; it certainly was and is a place that has had its own mind. Probably, a more accurate statement would be that California has been a creative state of mind.

These notions of being an imaginative step ahead are embodied by the stunning design exhibition California Design, 1930–1965: Living in a Modern Way, a presentation of a show originally developed by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2011. It offers more than 250 mid-century objects that demonstrate California’s position at the epicenter of Mid-Century Modern design. Mid-Century Modern is an architectural, interior, product, and graphic design style that generally covers aesthetic and technical developments in modern design, architecture, and urban development from roughly 1930 to 1965.

During this time, like Loewy and his colleagues did with the Avanti, California designers stripped fussy Victorian details, rococo flourishes, and various pieces of visual clutter from art, architecture, furniture, graphics, and fashion. The result was the sleek, often organic, modern look of a design-savvy, style-conscious emerging Atomic Age. California-based movies and later television shows spread and reinforced the new styles and designs both nationally and internationally.

A great example of stripped down, sleek, even minimalist design is the Airstream trailer that the visitor encounters before going up the stairs to the exhibition. This streamlined American icon was first created by Wally Byam in his Los Angeles backyard during the late 1920s. Its side door cut down on wind resistance and improved fuel efficiency. Now familiar as the sausage-shaped, gleaming, silver aluminum ship of the highway, Airstream trailers are a significant symbol of mid-century American mobility.

Economic expansion generated a vast influx of new California residents in the 1920s and early ’30s. This explosion was followed by the turmoil of the Depression, which didn’t stop the demand for new housing and furnishings, a need that was met by gifted and well-trained designers, artists, and artisans who had moved into the state. The lack of any powerfully established design styles in California, combined with a cross-cultural mix, encouraged these designers to be free to play with new and natural materials.

Demand domestically and internationally for California-produced products was driven by huge enthusiasm for California-based movies and later television programs. California became not only a travel destination but a lifestyle (or ‘look”) that could be purchased. Austen Barron Bailly, the PEM curator in charge of the installation, believes that “designers who embraced California modern wanted to make lives beautiful and comfortable. There’s something really timeless about that goal.”

Entering the exhibition gallery, the visitor feels through color, form, and spatial relationships a warm sense of optimism, creativity, experimentation, and exuberance. The objects in California Design were intended to be not only beautiful, but also salable. New materials and manufacturing techniques developed during World War II were adapted to mass-produce everything from ceramics to fashion to homes. California was a place whose culture prized innovation as well as experimentation.

Molded Wooden Leg Splint by Charles and Ray Eames, 1942–43. Photo: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

A great example of this spirit of innovation was the husband-and-wife team of Charles and Ray Eames. Californians by choice, Charles (1907–1978) and Ray (1912–1988) Eames are widely regarded as among America’s most important designers. Their innovations continue to influence contemporary design today. Interestingly, Charles was a noted architect, though he never finished college or got licensed, and Ray (Bernice) was an abstract painter who saw everything as a potential color study or painting. Much of their work is now iconic, and the show includes brilliant examples.

One of these is their legendary lightweight leg splint, a design that led to a new way in which furniture was thought about and made. At the beginning of World War II, the War Department immediately saw the need for a lightweight splint; existing leg splints were made of metal and would vibrate when carried on a stretcher, causing additional pain to the wounded. The US Navy commissioned the Eameses to create a light, inexpensive leg splint.

Earlier, in 1940, Charles had partnered with his friend architect Eero Saarinen to create a chair of molded plywood. Failing to make it suitable for mass-production or even very functional, they upholstered it to cover up its flaws. The chair ending up winning the Museum of Modern Arts’ “Organic Design in Home Furnishings” competition. It looked better than it sat.

Learning from this “mistake,” Eames never again began a design focusing on what it would look like, but instead concentrated on how it would function. When the Navy commissioned Charles and Ray to solve the splint problem, previous years’ of trial and error gave them the means to find a creative answer.

The design problem that needed to be overcome: how to create compound curves that would stay flexible, not splinter, yet were also lightweight and strong.

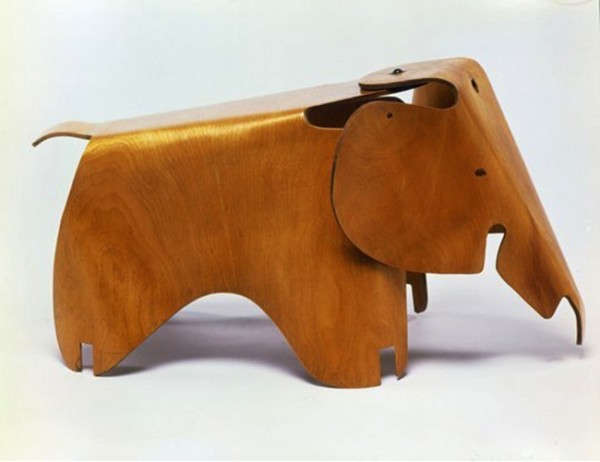

Having access to military technology and manufacturing facilities, the Eameses and their team of designers perfected their new technique for molding plywood. The final product had a three-dimensional, biomorphic form. Developing the leg splint led directly to the Eames’ subsequent and highly influential approach to creating molded plywood furniture designs. Original Eames chairs and an elegantly amusing toy elephant are examples of their superb craftsmanship in the exhibition.

Eames chairs became prime design objects of desire almost as soon as they were available. In 1945 Time Magazine deemed the LCW chair “the chair of the century.” Still manufactured by Herman Miller, the chair was called “the most advanced furniture being produced in the world today.”

There is more than a slight déjà vu quality to the show. Mid-Century furniture has had a resurgence in popularity for the past decade or so, recently driven by the popularity of TV’s Mad Men. A few pieces are still in production, and reproductions of many of them (not only by the Eameses) can be found today in stores or online, while the originals are still plentiful as deals on eBay.

What truly defined California living were the state’s distinctive homes and how people lived in them. The climate fostered an indoor/outdoor lifestyle. Central courtyards and swimming pools were wrapped in airy, open houses. Walls of windows and sliding glass doors created a seamless transition between inside and outside, room and yard.

The quintessential Californian domicile, complete with panoramic views of the mountains and clear sky, is the Kaufmann House in Palm Springs. Designed by architect Richard Neutra (1892–1970), the house is represented in the show by a photo by architectural photography pioneer Julius Shulman (1910–2009).

There are many high points here. Standout pieces range from furniture to appliances to fashion to decor. One major contributor to the California design legacy is German-born Kem Weber (1889–1963), an example of the kind of progressive European talent that enriched 20th-century American design. Two of his most iconic creations are on display. He designed for Lawson Time the brilliantly elegant copper digital—yes, digital—Zephyr desk clock (1933). It eloquently defines the style known as ‘Streamline Moderne.’

Also on view is perhaps Weber’s most famous work, the Airline chair of 1934. It exemplifies the clean, streamlined style of the age, with its seat supported by a cantilevered frame inspired by wooden aircraft components. The one on view came from a group of 300 made for the Walt Disney Studios (Weber was the primary architect for the Walt Disney Studio complex in Burbank, California).

Other great examples of design that are showcased in the exhibit: Group Artec’s 1950s and ’60s garden pottery and ceramic sculpture; a polyurethane foam, wood, and fiberglass cloth surfboard by Greg Noll of Hermosa Beach that says Pacific coast surfing, 1960; an elegant 1949 Lamp designed by émigré Greta Magnusson Grossman; the futuristic Buck Rogersesque, bright cherry red Ice Gun (Opco Company) from 1935; the wonderful 1950s record album covers from designers Saul Bass, Alvin Lustig, and William Claxton; the original Ken and Barbie dolls; and a fabulous boomerang pin by Margaret De Patta from c. 1946–57.

Toy elephant by Charles and Ray Eames, Molded Plywood, 1945. Photo: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

With clear and well-researched descriptions, the exhibition tells an enthralling visual story through its deft arrangement of the materials, styles, and forms that influenced California’s most influential and exciting design era.

The accompanying 360-page catalogue, edited by Wendy Kaplan, is co-published by LACMA and MIT Press, and features essays by Kaplan and Bobbye Tigerman, along with other leading architecture and design historians.

An urban designer, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox since 2002.

Tagged: 1930-1965: Living in a Modern Way, California Design, design, Mark Favermann

Nice article, but I have to point out a couple of problems with one of the illustrations: The photo of the Lawson Time “Zephyr” clock should be attributed to me, not the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It’s taken from My Collector’s Weekly page.

Also, the most recent research indicates that this clock was likely designed ca. 1936, not 1934, and not by Kem Weber. It appears in a 1938 Lawson Time catalog attributed to “Ferher and [George] Adomatis.” It’s thought that “Ferher” is a misspelling of [Paul] “Feher,” a well known Deco era metal smith who shared an L.A. apartment with artist George Adomatis in the mid ’30s. There’s more of the story here.

Thanks,

Dana Slawson

Los Angeles