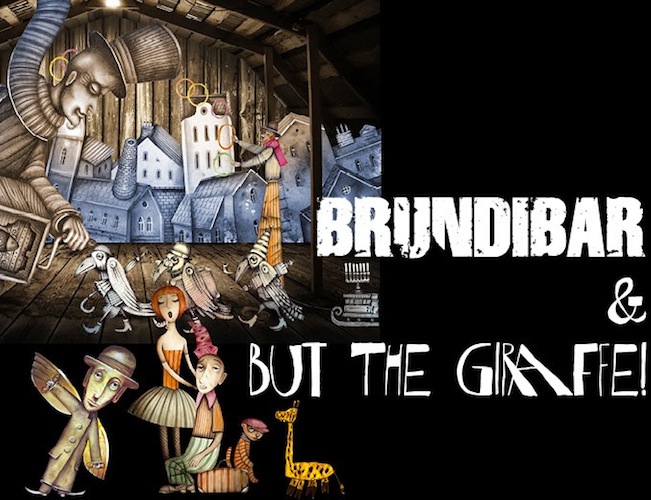

Theater Review: “Brundibár” and “But The Giraffe!” Serious Theater for Young People

The Underground Railway Theater production shows that sometimes children’s theater is capable of a moral depth (perhaps even a fearlessness) that adult theater often avoids.

By Ian Thal

Brundibár, music by Hans Krása, libretto by Adolf Hoffmeister, adapted by Tony Kushner. But The Giraffe! by Tony Kushner. Directed by Scott Edminston. Presented by Underground Railway Theater at Central Square Theater, Cambridge, MA, through April 6.

It is always noteworthy when a Tony Kushner play receives a professional production in the greater Boston area. Despite being one of the English language’s finest living dramatists, his works are not staged as often here as they deserve. Perhaps his work is just too intellectually ambitious, too complex, too politically nuanced, too challenging for our new play industry, which favors easy-to-take domestic dramas and pop culture pastiches with a side-order of identity politics. Perhaps the academic-theatrical complex still resents Kushner for modestly proposing the elimination of the undergraduate arts degree (he views such programs, now one of the key institutions of American theater, as having dumbed down the arts). Whatever the reason, Boston still has not seen a staging of The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism With a Key to the Scriptures.

In any case, a production of a Kushner play is a significant cultural event. Here he is writing for children in an adaptation of the Hans Krása opera Brundibár and his one-act companion piece, But the Giraffe!

Essentially a fairytale with a moral about how kind people must show solidarity against the cruel, Brundibár was composed by Krása and his collaborator, the librettist Adolf Hoffmeister, in 1938. At the time, Germany was threatening Czechoslovakia, eventually annexing the Sudetenland in one of a series of military aggressions that served as prologue to World War II in Europe. The opera was performed by the children of an orphanage in Prague. Even after German occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1940, its anti-Nazi message was largely ignored because it was composed in the Czech language. In 1942, Krása was among the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia who were arrested and interned at the Theresienstadt concentration camp in the garrison city of Terezin, as it was known in Czech. Hoffmeister, on the other hand, became a refugee, fleeing to France, Morocco, Portugal, and eventually New York before returning to Czechoslovakia after the war, where he lived until 1973 (though not without another brief period of self-imposed exile after the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968).

Theresienstadt was a medieval fortress converted into a ghetto and transit camp. The Jewish authorities that the Germans placed in charge of the population prioritized scarce resources for the education and well-being of the children of the ghetto. Krása reworked his opera and staged 55 performances as part of the children’s education.

Theresienstadt was marginally better than some of the other ghettos that Germany operated and served as a Potemkin village when, in 1944, the Danish and International Red Crosses, investigating reports of extermination camps and an overall program to exterminate the Jews of Europe (which the Polish Government in Exile had reported to the United Nations as early as 1942) paid a visit. In preparation for the visit, a significant part of the population was deported to Auschwitz to relieve overcrowding, and fake cafés and shops were built in order to give the appearance of affluence. After viewing the visit as a success, a propaganda film was authorized titled Terezin: A Documentary Film of the Jewish Resettlement—sometimes known as The Führer Gives a Village to the Jews. Both the Red Cross visit and the film featured performances of Brundibár. After filming, Krása, along with many of the inhabitants of Theresienstadt, were sent to Auschwitz, where he was murdered. Few of the child performers survived.

The opera, however, did survive, but with its history permanently connected to the ghetto. When author Maurice Sendak was preparing to adapt the opera as an illustrated children’s book, he found the existing English translation inadequate and recruited Tony Kushner to craft a new adaptation. When the resulting adaptation was staged in 2006, Sendak directed and designed the costumes and sets.

The tale follows two siblings, Aninku (Rebecca Klein) and Pepícek (Alec Shiman), who have been told by the doctor that their ailing mother needs milk if she is to recover. With no money to purchase milk, the brother and the sister take up busking in the market square, but Brundibár (John F. King), an organ grinder of flashy dress and mediocre talent, claims the square as his own and bullies the otherwise sympathetic police officer (Jeremiah Kissel) into protecting his turf.

With assistance from a dog (Phil Berman), a cat (Christie Lee Gibson), and a sparrow (Debra Wise), along with the children of the town, Brundibár’s domination of the town square is overthrown, and Annika and Pepícek earn enough money from singing to help their sick mother. Brundibár’s relevance to Hitler would have been obvious to audiences of the time, given that the tyrant’s earlier unsuccessful career as a painter was already well known. The message, however simple, was relevant to the lives of children as well as to Czechs before and after Germany’s invasion.

Kushner, aware of the fate of Krása and the children after the final performance in Terezin, added a less joyful epilogue in which Brundibár addresses the audience, warning that if he does not return someone like him will.

But The Giraffe! was written as a one-act curtain opener. While a children’s play, it has all the linguistic and moral sophistication one expects from Kushner. It serves as something of a prequel to Brundibár. Its young protagonist, Eva (Nora Iammarino), is caught in a moral quandary: The Jews of Prague are to be deported to parts unknown, and have been limited to a single suitcase and an additional item. Eva can pack her toy giraffe, Uncle All-Neck, or her beloved Uncle Rudy’s (Patrick Varner) copy of the manuscript of Brundibár, but try as she might, she cannot bring both. On one hand, the giraffe exists in an imaginative world in which objects are endowed with a soul; on the other hand, Eva is in love with her uncle and professes the intent to marry him once she is grown up. Meanwhile, the various family members—mother (Gibson), father (Berman), grandmother (Wise), grandfather (Kissel), and uncle—walk frantically on and off the stage making final arrangements for their deportation. Eva engages in dialogues with them as to which should be saved, the giraffe or the score. It is unclear if the adults are protecting Eva from the threatening truth, or if they truly have no inkling of their fate.

Kushner has densely packed this allegory. Giraffes “constitute a tribe unique in all the world,” yet they are like all other animals in that they have seven vertebrae in their neck—much as the Jews are different from other peoples yet universal in their humanity. (It is notable that both Jews and giraffes are mistakenly believed to have horns.) Eva’s duty to protect the giraffe was entrusted to her by Anton Moomek (King), the page boy of Mrs. Moola Wallabee, Queen of the Republic of Pik, one of the dolls already traveling with her family to Terezin. This resonates with the plight of the grandfather, a director of an orphanage who is sworn to protect the children “who have neither mamas nor papas,” though he realizes that he may be unable to do so in the months and years ahead.

Scott Edmiston’s major directorial conceit pays off in linking But the Giraffe! with Brundibár. He has staged Brundibár as if it was one of the performances by the children of Terezin. The false proscenium, the only gray part of an otherwise colorful set designed by Jenna McFarland Lord, recalls the arched ceilings of the fortress at Terezin. The youthful cast begin the opera after they wake up in the unadorned wooden bunks of the ghetto, while Varner, still dressed as Uncle Rudy, plays the nonspeaking part of the orchestra conductor (the ‘real’ music director is Todd C. Gordon). Reportedly, the children in the cast learned the biographies of the actual children in the ghetto. The distancing technique—the Underground Railway Theater’s youth ensemble play children who are likely to be shipped off in a cattle car bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau—creates a palpable emotional impact. (There is a developing subgenre in Holocaust theater that revolves around shows performed by inmates of Germany’s concentration camp system—Jonna Caplan’s one-woman show Total Verrükt!, which played last year at the Charlestown Working Theater, is another notable example.)

Ford’s scenic design for the home of Eva and her family and the opera in the arched halls of Terezin evokes both the idealized fantasies of fairytales and the looming threat of genocide. The costume design (Leslie Held) and puppets (designed by David Fichter and built by Brad Shur) are well integrated into the color palette. Fichter’s designs for the human-sized cat and dog puppets are well realized and give both Gibson and Berman freedom to fully perform on the stage, their singing unencumbered. The sparrow, a far more conventional rod-puppet, is nonetheless a beauty.

The ensemble in But the Giraffe! breathes Kushner’s distinctive poetry. Wise and Kissel bring a great deal of gravitas and humor to the grandparents, and Iammarino’s performance as Eva is invested with the intelligence and imagination demanded by the drama’s magical realist mode. Gibson and Berman express both the tragedy and comedy inherent in their roles as parents who must get the family ready to move into the unknown. Varner is charming as the erudite uncle who introduces his niece to the life of high culture.

In Brundibár, both Klein and Shiman demonstrate themselves to be charming performers with strong singing voices. Gibson and Berman also display considerable vocal skills while doubling as orchestra members, with Gibson on violin and Berman on harp, harmonium, and guitar. Of the puppeteers, Berman is the most technically adept, managing to imbue his performance as the dog with a great deal of canine nuance. In his roles both as Brundibár and as Anton Moomek, King moves his body with the precision, geometric and rhythmic, of a master puppeteer. Among the youth ensemble players, Zeke Iammarino (elder brother of Nora) is especially notable for his physically eloquent milkman.

The allegorical equation of bullies with tyrants, and thus bullying for military aggression, was obvious to both Krása and his collaborators, and to their original 1938 Czechoslovakian audience. It was the utter failure to confront bullying on a geopolitical scale that allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland, leading to the outbreak of WWII in Europe. This same pattern of not standing up to bullies in the international arena has reared its head again and again. Thus the ethical stakes allegorically present in Brundibár, whether in the Krása and Hoffmeister original, or in the context of the Terezin performance, remains relevant, while the evening also proves that sometimes children’s theater is capable of a moral depth (perhaps even a fearlessness) that adult theater often avoids.

Ian Thal is a performer and theatre educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere, and on occasion served on productions as a puppetry choreographer or dramaturg. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and is currently working on his second full-length play; his first, though as-of-yet unproduced, was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled From The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report

Tagged: Adolf Hoffmeister, Brundibár, But The Giraffe!, Hans Krása, Tony Kushner