Visual Arts Review: Cyberarts’s Art on the Marquee — Digital Game Shorts for Now People

Whether art can comfortably exist in this thoroughly commercial frame is a question for the ages. Let’s say that whether this show succeeds is firmly in the eye of the beholder.

By Margaret Weigel

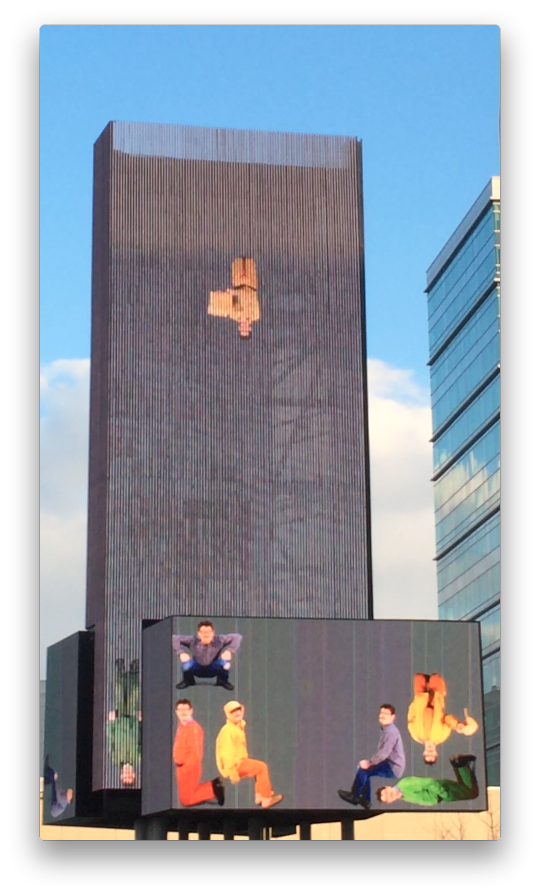

Sensory assaults that gobble valuable cognitive resources with their motion graphics and commercial messages? Photo: Boston Cyberarts.

Some people consider the massive digital billboards that line highways like I-93, grace the side of WGBH’s building that overlooks the Mass Pike, and loom outside the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center, to name a few sites, sensory assaults that gobble valuable cognitive resources with their motion graphics and commercial messages. OK, let’s face it. Most people think that digital signage is invasive, distracting and unattractive. Such are the fruits of innovation and capitalism. A 2007 NYT op-ed contributor spoke for many when he noted that these ‘nonconforming billboards’ are “1,200-square-foot behemoths that loom over the landscape atop 40-foot poles and which can be seen from miles away…programmed to flash a dozen ads in the driver’s face as he passes by.”

A local arts organization is working directly to provide digital content for a Massachusetts display. Boston Cyberarts, Boston’s leading organization promoting the connection between arts and technology, has partnered with the Boston Convention & Exhibit Center in South Boston to curate the content of the center’s approximately 3,000 square feet of digital display on Summer Street.

The marquee typically looks like: a narrow 80-foot tower (shown above displaying a city scene) and a more traditional rectangular frame at its base. Whether art can comfortably exist in this thoroughly commercial frame is a question for the ages. Let’s say that whether this show succeeds is firmly in the eye of the beholder.

Much of the work, unsurprisingly, capitalized more on the vertical dimensions of the frame, with figures falling or rising. A more pressing challenge is how, in a somewhat desolate business zone, to successfully design dynamic and engaging artistic content on an outside display. The time-tested solution for motion-based commercial displays is to keep it short and sweet: each of the artists in Art on the Marquee limit their work to approximately 30 seconds or so, hewing to the old dictum that the average amount of attention someone will give a billboard is eight seconds. However, these stats were taken from static billboards; perhaps passersby hungrily consume digital ones like their favorite screen activity.

If one didn’t know that the massive PAX East convention of video game developers and afficianados was taking place here April 11-13, one might wonder why the artists in “Art on the Marquee” chose to create game-like content. The single entrant that was not gamelike but merely digital was James Mannings’s Dirty Pixels, a digital manipulated out of old tape media.

The bulk of the collection reads like a series of simulacrum references to video game visual language. Many of the shorts resemble games – some of them even cite recognizable games. But they actually more closely resemble commercials for games that do not exist and for the act of gaming in general. This makes for a surreal experience, which is not wholly bad. The work at night, as the city background recedes into darkness, is transformed into luminous lunacy as figures fall and tumble through rectangles of light.

View of “Up” from the 3rd floor of the BCEC. All photos by Margaret Weigel unless otherwise credited.

Some of the shorts — Jeff Bartell & Fish McGill Trashteroids and Lina Maria Giraldo’s Up — strive to make a broad statement. Trashteriods’ outer space is cluttered with earthly debris; Up’s figures float in air above a pile of Tetris-like mountains of junk. Others provide a game-like view of an interesting but context-free landscape (Reginald Arlen DeCambre’s Permanence on the Sand).

My two favorites entries manage to use the vertical space extremely well as well as cram whimsy and meaning into a short frame of time. Jeff Warmouth’s Human Testbrix interprets the classic game of Tetris, but with Warmouth himself representing the bricks. Images of Warmouth in color-coded outfits and different positions fall from above and immediately click into a self-organizing pattern, creating a portrait of a life as an accumulation of selves:

and at night:

The award for the best use of the screen space goes to Eben McCue’s Super Life. In a thirty-second span, we watch the arc of a life from birth to death in classic game format. The baby morphs into a child on a playground, a football player, a working professional, and finally a retiree flanked by shuffleboard courts. Along the way, the protagonist is notified of his progress (“Leveled up: Boy” or “Rejected” as he flirts with a work colleague).

The graphics for the show by Cyberarts, interspersed with the artists’ shorts, feature splotches of paint and references to old-school bulb marquees. That a program of digital work in an innovative public space references the non-digital, non-motion past could be read as cheeky or as a hedge against those who still doubt that digital art and video games can be considered art.

Will passerby’s spend more than eight seconds taking in this collection of digital game-themed shorts? Is the brightness of motion imagery distracting for South Boston drivers? And what do the more buttoned-down denizens of the area, like the employees at nearby John Life insurance/Manulife think of their 80-foot video neighbor? Time will tell. I recommend that after a visit to the ICA for its Free Thursday Nights, take the local roads home and drive slowly past the BCEC around dusk. The show takes about seven minutes to watch; the experience may change how you think about public art, digital art and video games.

Margaret Weigel is a longtime Boston area arts and culture critic focusing on public art and the delineation of public/private space, shifting definitions of art, games, and audience engagements. @margaretweigel