Theater Review: “The After-Dinner Joke” — How We are Out-Sourcing Our Consciences

British dramatist Caryl Churchill proffers a valuable line of satiric attack on our delusions of doing good, so it is easy to forgive the dramatist her broad and scattershot comic approach.

The After-Dinner Joke by Caryl Churchill. Directed by Meg Taintor. Staged by Whistler in the Dark Theatre at the Charlestown Working Theater, Charlestown, MA, through November 24th.

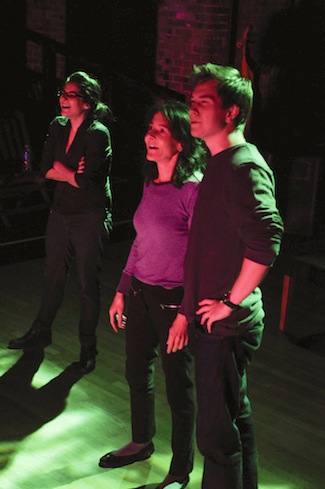

Melissa Barker, Lorna Nogueira and Joseph D. Freeman in Whistler in the Dark Theatre’s “The After-Dinner Joke.” Photo: Christopher McKenzie.

By Bill Marx

Perhaps the chances of doing real good in the world means ridiculing those who have been fooled into thinking they are. That is the promising satiric premise of dramatist Caryl Churchill’s amusing The After-Dinner Joke – a modern replay of Candide which was originally penned for BBC TV in 1978. A naïve, well-meaning young woman leaves the corporate world to dedicate herself to charity, hooking up with a company that wants to leverage its philanthropic efforts in ways that will both enhance its public image and benefit its bottom line. In contrast to Voltaire, Churchill suggests that unless you know who controls the land, the labor costs, and the political parties, as well as find out who pays off the police and in some cases the local guerillas, it doesn’t help all that much to send off funds to help the starving masses grow a (vegetable) garden. The poor remain on the bottom of the food chain, while the givers feel better about themselves and their good fortune, comfortably guilt free.

This is a valuable line of satiric attack on the glitz of modern mechanisms of manna, so it is easy to forgive Churchill her broad, scattershot approach. The Whistler in the Dark Theatre staging runs for 75 intermission-less minutes, its five performers sprinting (at times too breathlessly for the production’s good) through 66 hit-and-miss sketches that serve up an array of stereotypical characters. The actors are obviously having a lot of fun gender-switching in order to play multiple roles — farce material that should be sharply timed is handled a tad sloppily. The short bits spotlight the contradictory motives (and masks) of public and private do-gooders, with pokes at how charity is used to reinforce the ruinous status quo rather than genuinely change conditions for the better. There are mock-commercials, British politicians admitting that foreign aid makes the rich richer at home, ‘heart-breaking’ videos, silent film parodies, a Robin Hood of a mugger who is stealing and kidnapping for charity, and rapacious capitalists making ‘sympathetic’ visits to the downtrodden. Churchill looks at how government, the entertainment industry, and corporations hypocritically manipulate our impulse to help others in order to help themselves and screw the underprivileged in the process.

At the start, our innocent woman insists that assisting others around the world is an earnest activity that rises above ideology and commercial strategies. She learns to see that charity is all about politics. Of course, the cynical among us recognize that governments and corporations exploit the altruistic impulse to generate more profits, but that is accepted (particularly by Americans) as the price for doing the right thing for the right cause. (Would any company take on a politically controversial issue if it might make customers mad, to the point of cutting into profits? No way.)

Churchill uses laughter to question the morally questionable delusions of both the innocent and the cynical. Simply handing over money to charities for the feel-good glow is not enough: follow-up is essential, particularly an examination of where the funding is going and if it is doing the maximum amount of good. Because Churchill is on the left, that would mean giving money to struggling unions, which will fight for higher wages and better working conditions, rather than handing over food or building materials. (Most viewers will draw the line at funding guerilla forces, though perhaps Churchill isn’t serious about that option.) At its best, the humor in The After-Dinner Joke makes fun of our self-righteous gullibility, our worship of ease, and our love of celebrities. We out-sourcing our consciences — and the powers-that be are profiting by it.

Meredith Stypinkski in Whistler in the Dark Theatre’s “The After-Dinner Joke.” Photo: Christopher McKenzie.

All of this makes for tart comedy as far as it goes, but Churchill’s lampoon has dated. We desperately need an American update, though I don’t think any of our dramatists, or theater companies, has the courage to wade into controversial territory that could easily alienate wealthy subscribers or fat cat underwriters. The charity game has become much more sophisticated than when Churchill wrote The After-Dinner Joke — it is a sick black comedy now. Churchill’s gags about politicians taking pies in the face for charity (and votes) are wan compared to the savvy way in which corporations (aided and abetted by governments eager to assign its philanthropic responsibilities elsewhere) have convinced us that we can somehow shop our way to a better world. Big businesses get behind charitable causes in order to sell more products, creating a ‘compassion industry’ in which charities competitively market themselves to businesses with the clout to hire celebrities (Beyoncé, etc). Smaller charities are marginalized because they haven’t the requisite star power. I highly recommend a well-written 2012 book on the subject, Compassion, Inc.: How Corporate America Blurs the Line between What We Buy, Who We Are, and Those We Help by Mara Einstein (from University of California Press). Though she offers some solid advice on how to turn things around, Einstein is scathing about what the marriage of greed and branding has wrought:

Decades of consumer culture have taught us that any problem can be solved through the purchase of a product and disposed of just as easily. Now, that formula — with lots of branding money, the Internet, and celebrity bells and whistles attached –is being widely applied to charitable causes. We may hope that these new way of marketing will bring more people to care about good works, but given marketing’s history, it is far more likely these campaigns will give us just one more reason to feel good about buying overpriced consumer goods. The ultimate consequence of merging profits and purpose is further desensitization to those less fortunate, while doing little to engage people in meaningful altruism.

Given that some of our major theaters are using these same branding/showbiz techniques to sell their wares, I would not bet on seeing chic rhetoric about the questionable wisdom of fusing “profits and purpose” exposed on our stages, non-profit or otherwise. But over time the joke will not only be on those who have nothing. As Einstein suggests, those who have the inclination to care will end up caring less. The After-Dinner Joke may be antiquated, but its punch line still has some ethical oomph.

Tagged: Caryl Churchill, Charlestown Working Theater, The After-Dinner Joke