Book Review: “Necropolis” — A Book of the Russian Literary Dead

By J. Kates

This memoir offers an invaluable, broad look at intellectual Russia before and after the revolutions of 1917.

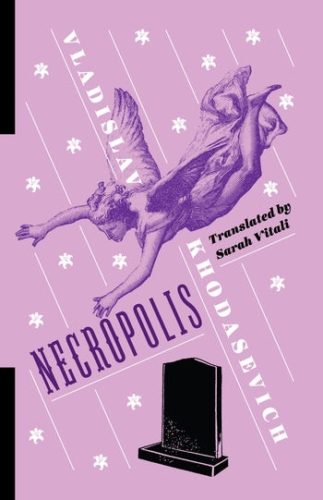

Necropolis by Vladislav Khodasevich. Translated from the Russian by Sarah Vitali. Columbia University Press, 304 pages, $14.95 (paperback), $30 (hardcover).

Pneumonia, sunstroke, three unspecified illnesses (two of them characterized as “a bad turn” and “he died of death”), an execution, and three suicides (gas, gun, hanging) were the entrance tickets into Vladislav Khodasevich’s memoir of early twentieth-century Russian literature, Necropolis (Некрополь). You had to be dead to be written in. If this sounds a little ghoulish, remember when Khodasevich was writing — and about whom. The author makes this rationale explicit: “I will not attempt to set forth here every detail . . . because I would be forced to go into too much detail about the lives of people who are still alive and well.” The living were under the shadow of, if not in the direct presence of, a Soviet political regime that threatened everyone. Khodasevich never states this directly, because he had to be circumspect, even in writing about circumspection, but it is clear.

Most of us know Vladislav Khodasevich, if we know him at all, only from Vladimir Nabokov’s use of him in Nabokov’s own fiction. But in his time, he was a figure of much talent and some importance, first in Russia and, after 1922, living abroad in Europe until his own death in 1939, the year of the original publication of Necropolis. Fortunately, we now have a fine selection of Khodasevich’s poems in translation by Peter Daniels (Arts Fuse review) and anyone wanting to read Necropolis could do worse than to begin with his own poetry. The prose Necropolis offers an invaluable, broad look at intellectual Russia before and after the revolutions of 1917.

For the most part, the living poet stays in the background in Necropolis. He is interested in his late contemporaries, both for themselves and for their place in Russian letters. When he is present it is as witness, a whiff of I only am escaped alone to tell thee flavors the narrative. Khodasevich was no name-dropper for the sake of names. He chose his subjects carefully and arranged them artfully. Each essay has its own focus, beginning with an account of a minor but significant figure,Nina Petrovskaya, who touched several of the lives of the others. A couple of the other names will be unfamiliar to most readers. The rest are well known. Khodasevich’s essay on Sergei Esenin is far more literary analysis than anecdote, while his portrait of Maxim Gorky explicitly shies away from literary criticism: “I am writing memoirs about Gorky, not an article on his work,” he specifies, just before looking closely at The Lower Depths, because it characterizes for Khodasevich “his entire literary oeuvre, like his life . . . permeated with a sentimental love for lies of all sorts and a stubborn, enduring distaste for the truth.” In his account of Andrei Bely, Khodasevich articulates his own modus operandi:

I feel compelled to be exceptionally fussy with the truth. I consider it my (far from easy) obligation to omit any hypocritical thoughts or euphemistic language from this account. You mustn’t expect me to offer up an iconic or canonical image of my subject. Such images are harmful to history. I am certain that they are immoral as well . . .

For all his disagreements with some of his subjects, a warmth of willful understanding permeates the writing. There is Valery Bryusov, who “bowed before the new autocracy of Communism,” and Fyodor Sologub, who “had never been young, and neither did he age.”

Sarah Vitali’s translation is lively and generally trustworthy. She has an annoying tendency to render the continuous past tense with an unnecessary English-language conditional — “Occasionally, he would attempt . . . Nina would pass . . . she would abandon herself . . . . She would lie on her sofa . . . would be gripped by fits of rage. She would break furniture . . .” All of these examples are from one paragraph; but this is so common in writing these days that I can hardly fault her for it. As for her translation of the poetry Khodasevich quotes, it is, unfortunately, no more than serviceable. But Vitali does provide a very handy index of names at the end to supplement the wealth of notes that guide the reader through the maze of specific cultural references.

Necropolis was written in the spirit of the blues, in the spirit of William Dunbar’s “Lament for the Makers,” lives celebrated in and illuminated by the knowledge of death. And underneath there is another oxymoronic portrait — that of Russia itself, its culture at home or abroad. In the words of one of Khodasevich’s poems, it is about choosing to live under submission — or longingly in exile. “My own Russia / I carry with me in my bag.”

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a non-profit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book book of translations is Paper-thin Skin, by Aigerim Tazhi (Zephyr Press 2019).

Tagged: Columbia University Press, J Kates, Necropolis, Russian, translation