Jazz CD Review: The Gil Evans Orchestra — Hidden Treasures, Vol #1

By Michael Ullman

Quite properly, Miles Evans evokes rather than mimics his dad’s arrangements on this excellent disc.

The Gil Evans Orchestra: Hidden Treasures, Volume One: Monday Nights (Geo Records)

In 1982, I went to lower Manhattan to interview bandleader, arranger and composer Gil Evans for an article commissioned by The Atlantic Monthly. Evans was then a hale, alert seventy year old who dressed like a hippie. He had recently released a vibrant album, Gil Evans at the Public Theater. I was enamored of his older music and excited by the new. Before I saw him I had recently heard the Evans orchestra play live, everything from rocking performances of Jimi Hendrix’s “Stone Free” to a medley of Charlie Parker tunes. On the record, Evans introduced Thelonious Monk’s “Rhythm-a-ning” with a few minutes of out-of-tempo electric sounds. No one had played Monk that way before. The legendary composer/pianist was in the moment, absorbing what he valued in the world around him and returning it in a wholly energized, personal way. His is my favorite version of Hendrix’s “Little Wing,” including Hendrix’s own.

But when I saw him for the interview he was having an epically bad day. He wanted to get out of the house so we sat on a bench outside his apartment house. After watching him sit despondently, staring at a tree that was growing out a pot in front of our bench, I asked him what was wrong. Evans said he had been keeping his scores in a large barrel for decades. That morning he discovered that his cat had been urinating on his manuscripts for years. Before I arrived, he had thrown out a portion (I never learned what portion) of his irreplaceable life’s work. Nonetheless, I struggled on with the interview. I asked him something about the band I had seen the previous spring. He said that was the past and he didn’t want to talk about the past. I asked him what he was currently writing and he said he wasn’t writing anything. With the present and the past ruled out of the conversation I asked about upcoming gigs. He said he had none.

I suggested we go for a walk. Marching around lower Manhattan, we met various people Evans knew. I particularly remember talking with pianist/composer Patti Bown. Eventually, Evans started to chat, telling me just about everything I wanted to hear for the piece … unfortunately, I wasn’t taping the conversation. He told me he had written the introduction to Miles Davis’s famous tune “So What.” He went on to say that he had attended and also done some arranging and writing for virtually every Miles Davis session that took place in New York. He wasn’t credited with any of this work, which shocked me. He didn’t seem to care (he might have, in fact) which shocked me even more.

Of course by that point Evans’ reputation was secure, though his finances might not have been. I noted that as early as 1957 critic Nat Hentoff had asked him what it feels like to be an “elder statesman.” Twenty-five years later, Evans still rejected the label: he was making new music, as he had since he led his first big band in the late ’30s. Trumpeter Jimmy Maxwell was in Evans’s California band, which in 1939 had recorded a tune called “Strange Enchantment.” Maxwell told me that even then Evans was interested in new sounds, adding (when he could afford them) French horns, tubas, and the occasional flute to the typical swing band instrumentation. Evans initially came to the attention to jazz aficionados through his arrangements for the Claude Thornhill band. He achieved popular fame through his arrangements on Miles Davis’s recordings, including Sketches of Spain and Porgy and Bess.

In the ’70s and ’80s Evans had a kind of renaissance: he recorded with his big band (Howard Johnson on tuba!) and his orchestra, backing up singer Helen Merrill (Collaboration, Emarcy). More surprisingly, given his predilection for dissing his own piano playing, he made brilliant duet records with Lee Konitz (Heroes, Verve) and Steve Lacy (A Tribute to Thelonious Monk), Still, if I had to guess, I’d say his heart was in the big band and the colors it could generate, now augmented with electronic sounds as well as buoyed by the occasional rock rhythm. He died in 1988.

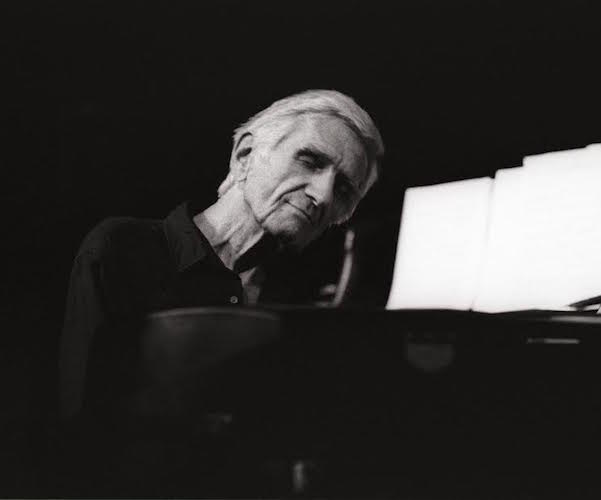

Gil Evans performing at the Public Theater during the early ’80s. Photo: Michael Ullman.

By the ’80s, one of his trumpet players was his son, Miles Evans, who is currently leading what he calls The Gil Evans Orchestra. The band’s pedigree is excellent: keyboardist Pete Levin, for instance, played with Gil Evans for over a decade. (Levin’s recordings with Evans commenced with 1971’s “Blues in Orbit”.) Other veterans of his dad’s band, such as John Faddis, appear on Miles’ beautifully recorded session, The Gil Evans Orchestra: Hidden Treasures, Volume One: Monday Nights.

Quite properly, Miles evokes rather than mimics his dad’s arrangements. The new orchestra doesn’t stress the early, politer Evans, but the outgoing music, sometimes aggressive yet still beautifully textured, that Evans made in his last years. The disc begins with Pete Levin’s “Subway,” which Gil Evans recorded on his Live at Umbria Jazz, Volume One. The new recording features both keyboardists that Gil Evans had used: Levin and Gil Goldstein. It also features a solo by trumpeter Faddis. Gil Evans’s version of “Subway” is self-consciously dramatic to the point of becoming a bit wacky: a band member pretends to be a conductor and yells out the names of stops, obviously celebrating when he arrives at 125th Street. The new version sounds more dignified than the original, but is just as theatrical, with the brass choir punching out a repeated short phrase only to be eventually overwhelmed by the rest of the band. From out of this massed sound a trombone solo emerges.

The band also plays Gil Evans’s arrangement of Mashiro Kikuchi’s “Lunar Eclipse.” Evans recorded this number repeatedly, including on an out-of-print collaboration with the composer and, more accessibly, on the 1977 disc Priestess. Amusingly, Gil Evans’ version of “Lunar Eclipse” begins with extreme delicacy: the percussionist Anita Evans, I believe, taps out a barely audible rhythm on what could have been chopsticks. Miles Evans gives this rhythm to the whole band, which plays it fortissimo. I imagine it’s a kind of in-joke, but it is also evidence of the band’s independence, interpreting music that invites playful reinvention but is beautifully elaborated.

The disc ends with a version of Gil Evans’ “Eleven,” a piece that has an interesting history. Miles Davis recorded his altered version of this piece, which Evans must have brought to him, as “Petits Machins” on June 19, 1968. (Chick Corea was the pianist for the track, which appeared on Filles de Kilamanjaro.) Gil Evans’ name isn’t mentioned on the record. He began recording his composition subsequently under the title of “Eleven.” (A version can be heard on Live at Umbria Jazz, Volume 2.) Its name probably reflects the complicated rhythms of the piece (try counting it). Three cheers for Miles Evans and his new orchestra for mastering this difficult composition and making it their own. And for giving it back to its composer.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. (He plays piano badly.)

Tagged: Geo Records, Gil Evans, Miles Evans, The Gil Evans Orchestra: Hidden Treasures