The Arts on Stamps of the World —October 22

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

Probably Franz Liszt and Sarah Bernhardt cast the longest shadows today, but writer Ivan Bunin, photographer Robert Capa, painter N. C. Wyeth, and actress Catherine Deneuve are all in the lineup, too.

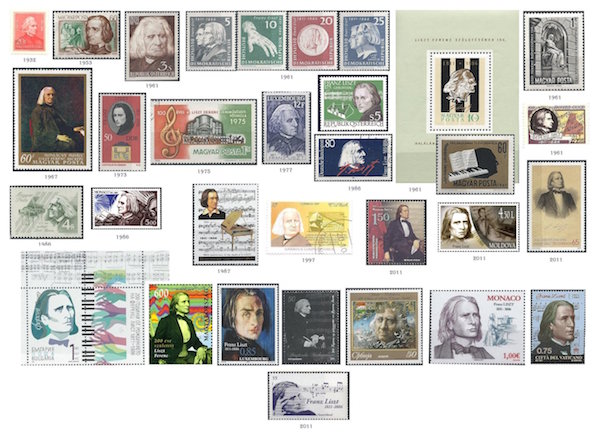

I think Franz Liszt (1811 – July 31, 1886) is greatly underrated and all too often sneered at. For an in-depth study, for those who have the time and inclination, I recommend the magisterial three-volume biography (1983-97) by Alan Walker. For now, I’ll just address myself to the vast array of philatelic tributes (for your part, feel free to skip the boring details and just look at the purty pitchas). The first stamp issued in his honor (upper left) came out in 1932, as one in a series of regular issues (what we collectors call “definitives” as opposed to “commemoratives”) of famous Hungarians. A souvenir sheet, too large to be included here and too expensive for my pocketbook, followed in 1934. A set of air mail stamps of various Hungarian composers was produced in 1953. 1961 saw a mini-explosion of issues for the sesquicentennial. Austria (one of my favorite designs), East Germany (with nods to Berlioz and Chopin), Hungary (of course), and Russia all honored Liszt that year. The oil portrait (second row left, by Mihály Munkácsy) appeared in a 1967 series of Hungarian art works. In 1973 East Germany came out with a set of stamps honoring famous men associated with the city of Weimar. The Franz Liszt Music Academy was remembered in a 1975 Hungarian issue. Two years later, Luxembourg entered the lists with a handsome portrait of the Abbé. The centennial year of Liszt’s death, 1886, saw another burst of issues from Austria (another gorgeous design), Germany, Hungary (of course), Mexico (not shown), and Monaco. The next year, North Korea put out a set of composer stamps, as did Cuba ten years later, both sets including Liszt. There followed a gap of fourteen years, more than adequately compensated for with a generous portfolio of bicentennial issues from Bosnia, Moldova, Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary (of course), Luxembourg, Macedonia, Mozambique (not shown), Serbia (a striking artistic conception), Monaco, the Vatican, and Germany (Marc-André Hamelin kindly gave me this one—at bottom center—on returning from a concert performance he had given there).

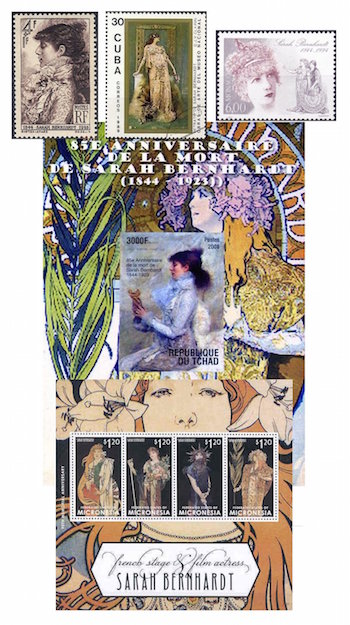

I suppose for many the name Sarah Bernhardt (22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) is synonymous with “actress”. Certainly she was not without her critics, and some pretty heavy-duty ones: G.B. Shaw, Turgenev, and Chekhov all panned her, but obviously her reputation has more than survived. She was born Henriette-Rosine Bernard in Paris to an unknown father and a Dutch-Jewish courtesan with a decidedly exclusive little black book. At school, 7-year-old Sarah took part in her first theatrical performance, but her 1862 professional debut was inauspicious, as she suffered from stage fright. But she settled in and by 1868 was sufficiently well known that when she lost her belongings in a fire, one of the performers for a benefit concert was no less a figure than Adelina Patti. During the Franco-Prussian War Bernhardt set up a hospital for wounded soldiers and nursed them herself, even assisting with amputations. (During World War I she would also perform for the troops at Verdun and the Argonnes.) Her first international tour was to London in 1879, and she undertook the first of her numerous American tours in 1880. While in New York, she visited Thomas Edison at Menlo Park, and he recorded her voice in a reading from Racine. In Boston she posed for photos on the back of a beached whale. Another tour in 1882 took her through Europe, with Bernhardt playing before crowned heads, and on subsequent ones she went around the world. In the 1890s she managed two theaters in Paris, the Théâtre de la Renaissance and the Théâtre des Nations, which she renamed the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt. She hired Alphonse Mucha to design posters for her productions. Bernhardt was one of the first to appear in motion pictures, her first one being shown by the Lumière brothers at the end of 1895. Her second film, L’Assassinat de Duc de Guise (The Assassination of the Duke of Guise, 1908) had a musical score by Saint-Saëns. Bernhardt had injured her leg while performing on stage in 1905 but neglected the injury for ten years, with the result that it required amputation, nearly to the hip, in 1915. She refused to wear a false leg and through various other devices disguised the fact in her subsequent performances. Sarah Bernhardt died of uremia in Paris. Her creativity found fruition in other areas: she wrote some short fiction along with a text on acting, painted a bit, and took sculpture quite seriously, having made a funerary portrait of her late husband Jacques Damala around 1889. (They had been married for only eight months, and Bernhardt never married again, though she had any number of lovers, including possibly the Prince of Wales.) The earliest stamp Sarah Bernhardt is a French one of 1945, issued a tad late for her centennial. In 1989 Cuba issued a reproduction of a painting of her as Shakespeare’s Cleopatra by Georges Clairin (1893). (The same artist had made an earlier portrait of her in 1876.) A stamp from Monaco came out in 1994, and in 2008 Chad issued a minisheet showing an 1879 portrait by Jules Bastien-Lepage (whose birthday is next week), with one of Alphonse Mucha’s posters in the background. Finally, there’s a new 2013 sheet of four from Micronesia, again with a Mucha girl peeking out, that was released for the 90th anniversary of Bernhardt’s death.

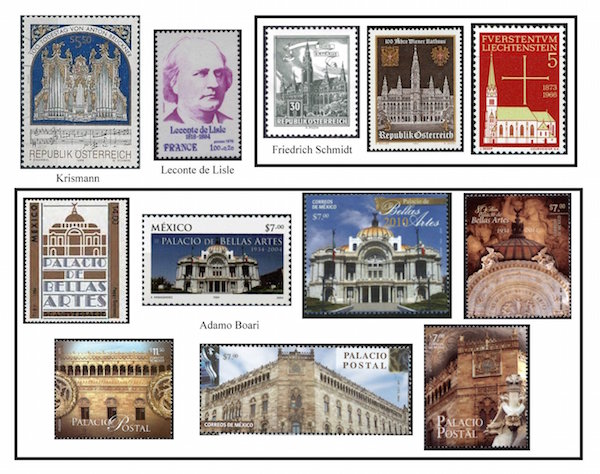

The 18th-century Austrian Franz Xaver Krismann (or Chrismann; 22 October 1726 –20 May 1795) was accepted into the priesthood right after learning his craft as an organ builder. His most famous construction is the instrument used by Bruckner in the Augustinian monastery of Sankt Florian. The composer is buried beneath the organ there. For Bruckner’s centenary stamp in 1996, the Austrian postal service used a design showing the organ built by Krismann.

The French poet Leconte de Lisle (22 October 1818 – 17 July 1894) was born Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle on the island of La Réunion in the Indian Ocean. He grew up there and in Brittany, resettling in Paris in 1845. His most famous works are the three collections Poèmes antiques (1852), Poèmes barbares (1862), and Poèmes tragiques (1884). At least five of his poems were set by Gabriel Fauré, with others put to music by Debussy, Ravel, Chausson, Duparc, and Reynaldo Hahn. Leconte de Lisle also wrote A People’s History of the French Revolution and A People’s History of Christianity and made numerous translations of the ancient Greek dramatists, Horace, etc. He succeeded Victor Hugo at the French Academy in 1866. There seems to be but a single stamp for him, but next year is his bicentenary, so we’ll see…

Next we come to one of the important Viennese Ringstraße architects, Friedrich Schmidt (1825 –23 January 1891). His work was by no means limited to Vienna, however. He was one of the primary architects called upon to complete Cologne Cathedral, which had lain unfinished for centuries, and upon which he worked for some fifteen years in the 1840s and 50s. He converted to Catholicism in 1858 and undertook another restoration for the cathedral of Sant’Ambrogio at Milan. Schmidt did not long remain in that city, though, as the Second Italian War of Independence compelled him to return to his birthplace. There he became a professor at the academy and built several churches. Again, he took part in yet another grand restoration, for St. Stephen’s Cathedral in the heart of the city. His most celebrated original work is surely his design for the Vienna City Hall (Rathaus), as seen on two Austrian stamps, and he also built the cathedral at Vaduz, Liechtenstein (1874, there’s a stamp for that, too) and St. Joseph’s Cathedral in Bucharest. He was ennobled as Friedrich von Schmidt by Emperor Franz Josef in 1888.

Another architect is up next, the Italian civil engineer Adamo Boari (October 22, 1863 – February 24, 1928), who did his most important work in Mexico. He was born at Ferrara, studied there and at Bologna, did some work in Turin, and then in 1889 removed to South America to organize an exhibition in Brazil. After visits to Buenos Aires and Montevideo he went to Chicago, where in 1899 he was allowed to practice as an architect and worked a bit in the office of Frank Lloyd Wright. It was in 1900 that he moved on to Mexico and produced several churches and residences, including his own. His grandest accomplishment, though he did not live to see its completion, was the Palacio de Bellas Artes, begun in 1901 but for various reasons, the Mexican Revolution among them, not finished until 1934. This building has been celebrated on a number of Mexican postage stamps, as has his Palacio de Correos de Mexico (aka Palacio Postal, finished in 1907), also in Mexico City.

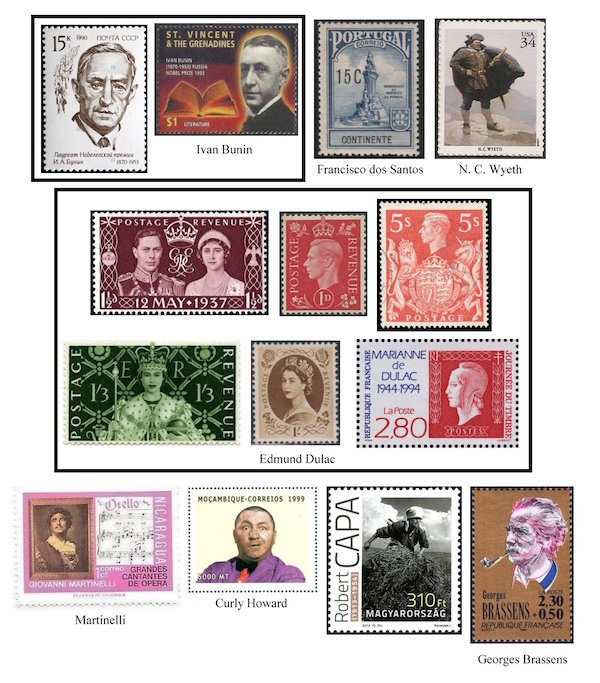

The first Russian writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature was Ivan Bunin (22 October [O.S. 10 October] 1870 – 8 November 1953). He had a happy and intellectually well-grounded childhood on the Voronezh estate of his rural gentry parents. It seems he exhibited a preternatural sensitivity to nature. Much of his education was derived at home from his brother, who had attended a university. Bunin’s first poem was published when he was not yet 17, and his first book of poetry was printed four years later, in 1891. It was only in 1895 that Bunin went to the capital, where he met and became good friends with Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky. The first volume of short stories dates from 1897, the first novel, a masterpiece, Antonov Apples, in 1900. To Gorky Bunin dedicated his 1901 poetry collection Falling Leaves, but he would begin to devote himself more and more to fiction in these years. He was in Odessa, Sofia, and Belgrade before coming to Paris with his second wife Vera Muromtseva in 1920. There he came to be viewed as the spokesman for expatriate Russians who had fled the Bolsheviks, admired for his devotion to the tradition of Tolstoy and Chekhov. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1933 and was urged to emigrate to the United States when World War II broke out, but he and his wife elected to remain in France, where they avoided trouble despite lending assistance to numerous fugitives in their mountain retreat. Bunin had the distinction of being the first Russian writer in exile to be officially published in the Soviet Union (1950s). A posthumous edition of his “complete” works appeared in 1965, although in fact some of his books remained under a ban until the 1980s.

Portuguese sculptor and painter Francisco dos Santos (October 22, 1878 – June 27, 1930) showed talent at an early age, such that he was enabled to enter the School of Fine Arts in Lisbon in 1893, to earn a scholarship to Paris in 1903, and to receive an allowance to go to Rome in 1906. In the meantime he had developed great skill in soccer and became the first Portuguese footballer to play abroad. He is described as the “main sculptor” for the monument to the 18th-century statesman the Marquis of Pombal in the square of that name in Lisbon. The stamp was issued to commemorate the nobleman, but serves our purpose admirably.

The father of Andrew Wyeth, whose centenary this year was marked by a handsome sheet of stamps from the USPS, and the grandfather of Jamie Wyeth, was Newell Convers Wyeth (October 22, 1882 – October 19, 1945), called N. C. Wyeth, better known as an illustrator. Wyeth was born in Needham—his mother was friendly with Thoreau (who shares a birthday with Andrew) and Longfellow—and attended art schools in Massachusetts. Further studies under Howard Pyle were followed by a 1903 cover for The Saturday Evening Post, his first professional assignment. Later he would work for Scribner’s and its offshoot, the Scribner Classics, for which his first assignment, Treasure Island, was a great success, the proceeds from which enabled Wyeth to afford his own studio. On the stamp we see one of the pictures, “Captain Bill Bones”, from that 1911 edition. Ultimately Wyeth would provide illustrations for over a hundred books. Wikipedia tells us he also created “posters, calendars, and advertisements for clients such as Lucky Strike, Cream of Wheat, and Coca-Cola, as well as paintings of Beethoven, Wagner, and Liszt [!] for Steinway & Sons.” But by 1914 Wyeth was becoming disgusted with commercialism. He always made a clear distinction between commercial art and painting. Wyeth’s friends, incidentally, included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hugh Walpole, Lillian Gish, and John Gilbert. He was killed, along with his small grandson, also named Newell, when their car stalled on a railroad crossing near their Pennsylvania home.

Another magazine and book illustrator, Edmund Dulac (October 22, 1882 – May 25, 1953), happens also to be the first of two stamp designers we look at today. Born in Toulouse, (as “Edmond”), Dulac moved to London at a young age and as his first commission illustrated the novels of the Brontë Sisters. He became a naturalized British citizen in 1912. Dulac’s stamp designs included those for the coronations of George VI and Elizabeth II. The former design is shown adjacent to the 1p denomination of the George VI definitive series. Dulac designed the head but not the surrounding decorations, except for two of the higher value varieties (the 5 shilling is shown). Just the reverse was true for the 1953 coronation stamps—that is, Dulac designed the differing frames (for three of the denominations) but not the image of the queen. During World War II he also created designs for banknotes and for the so-called Marianne de Londres series of stamps for Free France. A French anniversary issue from 1994 provides an example.

Giovanni Martinelli (October 22, 1885 – February 2, 1969), one of the most admired tenors of the 20th century, gave nearly a thousand performances at the Met over 32 seasons beginning in 1913. In that year he married Adele Previtali (any relation to the conductor? I can’t find out); they remained together for 55 years until his death in 1969. The stamp comes from an opera set we’ve seen before, issued by Nicaragua in 1975.

Well, we’ve already saluted all but one of the Three (actually four) Stooges, and today is the day we wind up with Curly Howard. Jerome Lester Horwitz (October 22, 1903 – January 18, 1952) was quite an accomplished basketball player, ballroom dancer, and singer in his pre-nyuk-nyuk days. Just as Larry Fine suffered a crippling accident in childhood, so did Jerome: he accidentally shot himself in the left ankle with a rifle when he was 12, and the injury left him with a permanent limp, which he disguised by exaggerating his walk. He was forced to step down from the Stooges following a stroke in 1946.

Hungarian-born American photographer Robert Capa (born Endre Friedmann;[1] October 22, 1913 – May 25, 1954) was one of our most remarkable and daring photo journalists. He was born with the name Endre Friedmann to a Jewish family in Budapest. He fled the country at 18 for fear of arrest for his communist sympathies and went to Berlin, where he found work in what grew to be his love, photography. Again driven abroad, this time by the deadly anti-semitism of the Nazis, he removed to Paris, where he met and fell in love with another Jewish photographer, Gerda Taro. It was in France, not America, that he changed his name to Robert Capa, again as a consequence of anti-semitism. His first published photograph was of no less a figure than Leon Trotsky; this was in Copenhagen in 1932. Capa documented the Spanish Civil War with Taro, who was killed in a motor vehicle accident involving a tank. (4,500 negatives that they took with David Seymour, thought for decades to have been lost, turned up in Mexico in 2007. A film, The Mexican Suitcase, was made about it in 2011.) Famous for his war photography, Capa caught images in 1938 China, 1943 Sicily, and on D-Day (he was the only civilian photographer on Omaha Beach). Again, a deplorable loss occurred when all but eleven of the 106 photos Capa took that day were accidentally destroyed in London. The surviving shots are known as the Magnificent Eleven. In 1945 he had a brief relationship with Ingrid Bergman. In 1947 he founded Magnum Photos in Paris with Henri Cartier-Bresson and traveled with John Steinbeck to Russia for Steinbeck’s book A Russian Journal. For Life magazine he went to Southeast Asia in 1954, where his luck deserted him—having escaped the Holocaust, survived the Spanish Civil War and the Japanese in China, and come safely through the Allied invasions of Europe, Capa was killed by a land mine at the age of 40.

On a lighter note, French singer-songwriter Georges Brassens (22 October 1921 – 29 October 1981) wrote the poems he turned into songs and accompanied himself on the guitar. Not only did he use his own lyrics, more than a hundred of them, but he turned also to such sources as Victor Hugo, Paul Verlaine, and Louis Aragon. Born in the south of France near Montpellier, he worked in forced labor near Berlin during the war; but being given a leave of absence, he escaped and remained in hiding in Paris for months. Brassens recorded fourteen albums between 1952 and 1976. He never learned to read music.

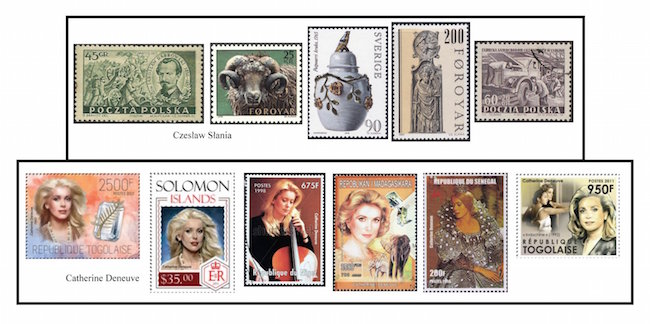

Probably the most admired of all stamp designers among collectors is the Polish engraver Czesław Słania (CHESS-swahf SWAH-nee-a; 22 October 1921 – 17 March 2005), who created over a thousand stamps for more than two dozen countries, many for Poland and Sweden, where he lived from 1956. During the war, Słania forged documents for the Polish resistance. At war’s end he attended the Kraków School of Fine Arts. His first stamp design was for a 1951 issue honoring the 19th-century military commander Jarosław Dąbrowski. The 1000th we’ve actually already seen, as it commemorated the Swedish portrait painter David Klöcker Ehrenstråhle, whose birthday we noted here last month. I show a more-or-less random assortment of Słania stamps. He also engraved many banknotes, including this one for Canada.

Finally today, we salute French actress Catherine Deneuve (born 22 October 1943), born Catherine Fabienne Dorléac in Paris 74 years ago today. Her parents were stage actors, as were her sisters Françoise and Sylvie. Catherine Deneuve’s first film appearance was with Sylvie in a small role in Les Collégiennes (1957). Her breakout role was in the musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), and she went on to work in such acclaimed films as Repulsion (1965, Polanski), Belle de Jour (1967, Buñuel), and The Last Metro (1980, Truffaut). Between 1985 and 1989 Deneuve’s face was one of those used to represent the French national symbol of Marianne. Some may recall that she was also the face of Chanel No. 5 in the late 1970s. She speaks fluent Italian and English besides her native French, and is conversant in German. She was married only once, to photographer David Bailey, but was romantically involved with director Roger Vadim and Marcello Mastroianni.

Not yet appearing on any stamps that I know of but destined I’m sure for philatelic recognition are British novelist Doris Lessing (22 October 1919 – 17 November 2013) and American painter Robert Rauschenberg (October 22, 1925 – May 12, 2008), and happy birthday to English actor Sir Derek Jacobi (born 22 October 1938).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.