The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 6

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

Today is the birthday of François Truffaut and Claudio Arrau and the 520th anniversary of the death of Johannes Ockeghem. We also salute a variety of other creative persons on this February 6th.

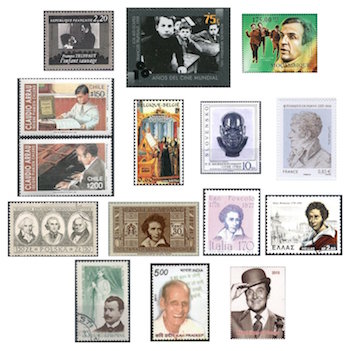

François Truffaut (6 February 1932 – 21 October 1984) had the kind of childhood that so often leads to a failed life: born to an unwed mother (his father was probably a dentist named Levy), shuttled from one caretaker to another, the best of whom was his grandmother, who died when he was eight, a truant expelled from several schools, etc., but Truffaut was saved by his gifts, and the troubles of his youth informed much of his work. His wonderfully rich career was cut short by a brain tumor, and his death at age 52 robbed us of more treasures. Of the three Truffaut stamps I could find, the one at left gives us a scene from L’Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child, 1970), the one at right cites Jules et Jim (1961), and the Argentine one at center gives us a still from his first and perhaps finest feature, The 400 Blows (Les Quatre Cents Coups, 1959). The French and Argentine stamps are drawn from sheets honoring various filmmakers, whereas the one from Mozambique comes from a souvenir sheet dedicated exclusively to Truffaut.

Like Truffaut, Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau (1903 – June 9, 1991) never knew his father, who died when Arrau was a baby, but was born into much better circumstances to distinguished families of Spain and Scotland. His mother was a piano teacher. Arrau went to Europe on a government grant when he was eight, but his teacher in Berlin, Martin Krause, a Liszt pupil, died when Arrau was 15, and the bereaved Arrau never took formal lessons again. He was also self-taught in other disciplines, reading widely during his travels over the years and learning English, Italian, German, and French along the way. Before he was twenty he had renounced his Catholicism. In the mid-1930s Arrau began giving series of recitals that presented the “complete” solo keyboard works of the great masters: twelve Bach programs in 1935, five for Mozart the next year, etc. He played all the Beethoven sonatas in 1938 in Mexico City and repeated that feat on a number of later occasions. In 1937 he married the German mezzo-soprano Ruth Schneider (1908–1989), but they and their two daughters (a son would follow in 1959) left Germany in 1941 for the United States. Arrau lived in New York City for the rest of his life (though he died in Austria following surgery), becoming a dual national (U.S.-Chilean) in 1979. Claudio Arrau’s students included Garrick Ohlsson, Roberto Szidon, and Stephen Drury.

The name Johannes Ockeghem appears in various period manuscripts and documents as “Okeghem,” “Ogkegum,” “Okchem,” “Hocquegam,” and “Ockegham,” among other things. His place of birth is moot (could be Saint-Ghislain, Belgium), and his year of birth could be as early as 1410 or as late as 1430! These are odd lacunae for a composer often regarded as the most famous and influential of his day. We know he served at the court of Charles I, Duke of Bourbon, in Moulins, France, from 1446 to 1448 and that he was at court in Paris from around 1452, serving Charles VII and Louis XI. He took part in a diplomatic mission to Spain in 1470, but the latter part of his life is almost as obscure as the earlier, except that he went to Bruges and Tours after the death of Louis XI in 1483. Ockeghem’s compositional corpus is relatively small: 13 authenticated masses, a Requiem, a Credo, five motets, and 22 chansons, one of them a motet-chanson (a deploration on the death of Binchois). Many laments, including one penned by Erasmus, were composed after his death on February 6, 1497, the most famous of them being the one by Josquin des Prez.

Permit me to anticipate your question. I don’t know whether 18th-century sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736 – August 19, 1783) was in any way related to his later namesake, aircraft designer Willy Messerschmidt. The former is known for his really extraordinary series of most unusual busts, character heads exhibiting extreme facial contortions, as exemplified in the Slovakian stamp shown here, though this is a rather mild example. Messerschmidt, born in Swabia, grew up in the home of his sculptor uncle and after study at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna was employed by the imperial court, creating perfectly conventional busts, including some of members of the royal family and one of Franz Anton Mesmer. But it seems Messerschmidt began to suffer from paranoia and hallucinations and was eventually dismissed from his teaching post at the Academy, partly, one assumes, because of the bizarre nature of his work: heads with grimaces of various kinds, wide-open mouths, eyes squeezed tightly shut, tongues stuck out, that sort of thing. He did a lot of these, and they are really quite weird and wonderful.

French poet Évariste Desiré de Forges, vicomte de Parny (1753 – 5 December 1814) was born on Réunion (known then as the Isle of Bourbon), though at age ten he and two brothers were sent to France for their education. Opting for the clergy, then the military, he wrote his first published poems after a disappointment in love, and this work made his name as a poet. His military career next took him to India, where he composed his Chansons Madécasses, much later to be set by Ravel. Nonpolitical in orientation, Parny got through the Revolution unscathed, albeit strapped for cash. He worked in government positions in Paris for the remainder of his life. A local connection: in 1777 he wrote an Épître aux insurgents de Boston (Letter to the insurgents in Boston).

Julian Niemcewicz (1758 – 21 May 1841) is more significant historically as a statesman, but he also wrote poems and plays and a novel, John of Tenczyn (1825), after the manner of Walter Scott. His earlier political comedy, The Return of the Deputy (1790), was quite a hit in its day, and besides his poetry he also wrote a History of the Reign of Sigismund III (1819) and six volumes on ancient Polish history (1822–23). Unfortunately, he also wrote an anti-semitic pamphlet in which he describes a dystopian future (the year 3333, no less) resulting from an insidious international Jewish conspiracy. A supporter of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, an aide to Kościuszko, and finally a high-ranking government official, Niemcewicz (pronounced n’yem-TSEH-vitch) is shown on this 1973 Polish stamp along with two prominent contemporaries. (OK, I admit it, I don’t know whether “J. Śniadecki” is Jan Śniadecki [1756–1830], mathematician, philosopher, and astronomer, or his brother Jędrzej [1768–1838], physician, chemist, and biologist. “H. Kołłątaj” is undoubtedly Hugo Kołłątaj [1750–1812], priest, activist, political thinker, historian, and philosopher.)

Like the Vicomte de Parny, Ugo Foscolo (1778 – 10 September 1827) was born on an island, in this case Zakynthos, and left it at age ten for his father’s homeland, in this case Venice. (His mother was Greek, thus the Greek stamp beside the two Italian ones.) Politically minded, Foscolo admired Napoleon, who was expected to bring republicanism to then oligarchical Venice, but felt betrayed when Napoleon presented the city to the Austrians with the Treaty of Campo Formio. A result was Foscolo’s novel The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis (1798), seen as a more politicized variant on Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther. He left Venice for Milan and, still hopeful for Venetian independence, joined the French army and was wounded and captured. On his release he began work on a translation of Laurence Sterne’s Sentimental Journey. But some of his subsequent work was seen as anti-Napoleon, and he decamped for Tuscany and, when the Austrians entered Milan, for England. There he lived his last eleven years, earning his living (to some extent—he also spent some time in debtors’ prison—with contributions, in both Italian and English, to periodicals. His finest work may be the long poem “Dei Sepolcri” (1807).

Online information on Romanian tenor Ion Băjenaru (1863 – 5 November 1921) is scanty. He studied at the Bucharest Conservatory and shortly (?) after graduation was engaged at the Romanian Opera. He seems to have specialized in operetta, appearing in The Gypsy Baron, The Merry Widow, Boccaccio, and the first Romanian performance of Les cloches de Corneville, though he also sang Cavalleria rusticana. As an amusing aside, Google’s well-intentioned translation bot seems to cite one of his vehicles as Money Hell. I can’t for the life of me figure out what opera title that’s supposed to be! (Offenbach’s Monnaie aux enfers? Rimsky-Korsakov’s Le Chthon d’Or? Or maybe an aria like Verdi’s “Il dinaro è mobile” or Mozart’s “Der Hölle Reichtum”?)

A writer of poems and songs (some 1700 of them, many of them patriotic in nature and subject), Kavi Pradeep (1915 – 11 December 1998) was born Ramchandra Narayanji Dwivedi into a middle-class Brahmin family in a small central Indian town. He got into a bit of trouble for contributing a song called “Move Away O Outsiders” to the 1943 Indian hit movie Kismet. Pradeep had to go into hiding to avoid arrest by an incensed Raj. But his popularity was enormous, such that people would often attend movies (he wrote songs and lyrics for 72 of them) just for another chance to hear the songs. His best known was a patriotic song called “Aye Mere Watan Ke Logo” that he wrote as a tribute to the soldiers who had died during the Sino-Indian War of 1962. Pradeep received the Dada Saheb Phalke Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cinema in 1997.

Despite a long career, the late Patrick Macnee (1922 – 25 June 2015) will no doubt always be remembered first and foremost as John Steed in The Avengers. Expelled from Eton for selling porn to his classmates, he served in the Royal Navy in World War II, appeared as an uncredited extra in Olivier’s film of Hamlet, and lived in the US from the 1970s, becoming a citizen in 1982. He worked a lot in television, and some of his other film roles were in the Bond flick A View to a Kill (1985), the campy werewolf movie The Howling (1981), and, unforgettably, as Sir Denis Eton-Hogg in This Is Spinal Tap (1984). He died in Rancho Mirage at the age of 93.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.