Music Preview: Michael Gibbs — Coming Full Circle at Berklee

The evening will be an invaluable opportunity to hear sounds, textures, and melodies created by a veteran composer/arranger.

Michael Gibbs Directs the Only Chrome Waterfall Orchestra (featuring Gary Burton, Bill Frisell, and Jim Odgren) at the Berklee Performance Center, 136 Massachusetts Avenue, Boston, MA, October 19 at 8 p.m.

Composer/arranger Michael Gibbs. Photo: courtesy of Cuneiform Records.

By Michael Ullman

Born in Zimbabwe and currently residing in Malaga, Spain, composer/arranger Michael Gibbs is celebrating his 80th year with a concert in Boston (featuring musicians Gary Burton, Bill Frisell, and Jim Odgren) in which he will recreate the sound of some of the now legendary big band music he wrote for Berklee College Orchestras in the ’70s. Gibbs’s local connection goes back even further — to his childhood. In his homeland, he had a teacher who first turned him on to Louis Armstrong (a tactful influencer), and from there sent him to the modern jazz of Gerry Mulligan, Shorty Rogers, and Dave Brubeck. His other source of popular music knowledge, Gibbs told me in a recent telephone interview, was the Voice of America, where he heard two pieces that “bowled [him] over.” They were the New Orleans trumpeter Bunk Johnson’s “When the Saints Go Marching In” and Billie Holiday’s “Don’t Explain.” Finally, the year Charlie Parker died, 1955, he heard the great saxophonist.

Parker made an enormous difference. Before that, Gibbs planned to go to the West Coast to study jazz trombone. Parker “shifted my interest from the West Coast to Kansas City.” (Evidently he thought Kansas City was close to the East Coast because, in 1959, he enrolled at Berklee as a trombone student). He went from having “not seen anything” to being immersed in the Boston music scene, including taking in live performances at places such as George Wein’s Storyville. He decided to study arranging. He took the three classes that were then available at Berklee, which at the time it was not a degree-granting institution. All three courses were taught by “his mentor,” a Boston legend, the trumpeter and arranger Herb Pomeroy. Pomeroy invited him to the famous Lenox School for Jazz for a summer: Gibbs ended up playing trombone in a band conducted by the great bop trombonist J.J. Johnson. Freddie Hubbard, then 22, played trumpet in that band. At the same time, he was being taught about chromaticism with the legendary composer-theorist George Russell, who would finish his career as a professor at the New England Conservatory. The result: “Every time I write a piece or arrange a piece, I always have as my palette the chromatic scale.” He found Pomeroy’s discipline bracing and Russell’s theory liberating.

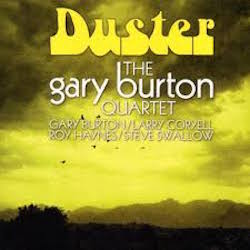

Gibbs started writing music at Berklee for his buddy, vibist Gary Burton: Duster, Burton’s 1963 recording, features three Gibbs numbers: “Liturgy,” “Ballet” and a piece that became something of a hit when it was recorded by Stan Getz, “Sweet Rain.” Gibbs found himself on his way to becoming a successful jazz composer. As it turned out, he was also on his way to London for about a decade. There he wrote widely, including music for a British comedy TV show The Goodies as well as some of the music for Tales from the Darkside. He arranged for dozens of pop singers whose voice he never heard. He’s never been a snob or parochial: he’s worked with Elton John, Whitney Houston, and Peter Gabriel, as well as for Joni Mitchell (Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter). He learned something particularly important during the Mitchell date. He was at first nonplussed by the power of Mitchell’s lyrics. What more was needed? He heard, though, a line about a river snaking, and that made him think of an oboe. A two-note pattern popped into his head. He searched for the “little spot” where he could built into, and out of, his addition. “When I write these things, the project doesn’t always start at the beginning and go to the end. I find little bits that come to mind and work around them.” In terms of jazz, he’s written for Buddy Rich as well as for Jaco Pastorious, the doomed bass player he met at Berklee, and for another great electric bassist, Stanley Clarke.

His heart seems to have always been with jazz. In 1974, he returned to Berklee as a teacher and an ensemble leader. By that time he had written numerous pieces for Burton, including two major suites: In the Public Interest and Songs for Quartet and Chamber Orchestra. In 1976 at Berklee he met the other honoree at Thursday’s performance, guitarist Bill Frisell. “His going to Berklee was influenced by his having discovered my music with Gary Burton’s band,” Gibbs recalls. In 2015, Frisell invited Gibbs to Seattle to collaborate on a recording of a student band playing some of Frisell’s compositions: “It was like coming full circle.” The concert on Thursday night will complete a different circle. There, Gibbs will be leading another youthful Berklee band, the Berklee Concert Jazz Orchestra, in compositions (the program is not yet set in stone) he conducted three decades ago — and with some of the show’s featured stars. The evening will be an invaluable opportunity for Bostonians to hear sounds, textures, and melodies that wouldn’t have happened, at least in the same way, without the indispensable wisdom and talents of a variety of Boston musicians, legends all.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.