Visual Arts Review: Francis Picabia — A Chameleonic Modernist

Francis Picabia may be the finest modernist you’ve never heard of.

Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, through March 19.

A section of Francis Picabia’s “Aello.” 1930. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Photo: Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

By Charles Giuliano

In bits and pieces, mostly by way of intriguing but enigmatic works dispersed among various museum collections around the world, the chameleonic work of French artist Francis-Marie Martinez de Picabia (1879 – 1953) is coming into its own.

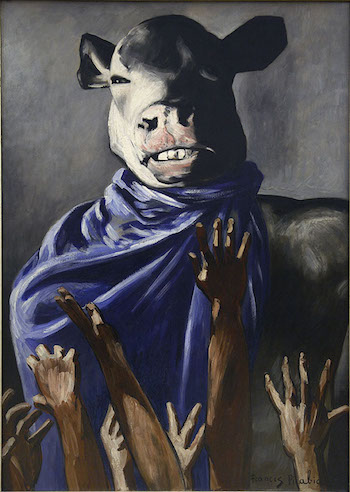

Because of the artist’s restless, eclectic diversity, the MoMA retrospective generates the manifold sensibility of a group show. Moving from room-to-room amounts to an exhaustive survey of 20th century modernism. We start with post impressionism then encounter periods of Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, Fascist kitsch (created in Vichy France), a period of uniquely painted palimpsests, then a variety of approaches to abstraction.

In order to stay fresh, Picabia suggested changing styles as frequently as we change shirts. His customary approach was embrace a style, eventually reject it, and then ridicule what he had done. For example, after he abandoned Cubism for Dada, he nastily proclaimed that “Cubism is a cathedral of shit.” Marcel Duchamp, with whom he may be compared, was more enigmatic; when he abandoned painting he called it “too retinal.”

When Picabia rejected surrealism, his exit strategy included renouncing Andre Breton, the autocratic theorist and leader of the movement. This kind of abuse was a switch, given that Breton was the one who censured and then ejected artists who hadn’t lived up to the purity of his ideals. Breton imposed rules on the anarchy of Dada after World War I; but Picabia was not the kind who would accept anyone’s limits on art, so surrealism was to be used and then abused;

How could Picabia be so cavalier? He was a man of means, born to wealth on both sides of his family. His father was Spanish/ Cuban and his mother was French. She died young and he inherited a fortune from her. In addition, the artist was handsome and amorous; his companions describe him as a prankster and playboy. He loved fast cars, gambling, booze, beautiful women, and dope. He is the model of the modern artist as heat-seeking missile; always in the right place at the right time for the maximum amount of excitement.

“L’Adoration du veau,” Francis Picabia, early 1940s, Centre Pompidou. Photo: Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Picabia was in New York for the seminal 1913 Armory Show, which introduced avant-garde European art to America. Based on the succès de scandale of his “Nude Descending a Staircase,” Duchamp also visited New York.

The French artists became integral to the NY Dada circle that showed with Gallery 291 of the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The gallerist/ artist gave Picabia a one-man show as well as an entire issue of his publication 291. Both Picabia and Duchamp commuted between Paris and New York.

Picabia created his most iconic works when he embraced an art mechanique style inspired by Dada. His image of a small, bellows camera — unfolded in profile — was the portrait on the cover of a 1915 issue of 291: “Ici, c’est ici Stieglitz, foi et amour.” The picture predates Magritte’s famous “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” A generous selection of the retrospective focuses on his distinctive and aesthetically satisfying Dada/ mechanique graphics for 291 and his own later 391 magazine, which he launched in Barcelona in 1917.

Text was also important to the artist. In painting and collages, particularly after joining the Zurich school of Dada — led by Tristan Tzara — words, often treated in a disconnected manner, became a prominent part of his collages and paintings with collaged elements. One senses the same restless linguistic experimentation in these works as is to be found in the creations of Guillaume Apollinaire and his friend Gertrude Stein.

Francis Picabia’s “Tableau Rastadada” (1920) is one of the masterpieces he contributed to the Dada canon. Considered to be his first collage, at its center is a photo of Picabia by Man Ray. It is partly mutilated by a comical, small bowler hat, which is pasted on. A pipe dangles from a nostril and the composition is framed with images of women’s ankles and shoes. The word ‘Papa’ has been written in and crossed out. In a self-deprecating gesture, the artist has inscribed “Picabia Le Loustic” — outing himself as a “joker.”

Aristotle’s influential Poetics regarded comedy as inferior to tragedy. In his 1938 book Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga challenged that venerable prejudice, arguing that serious fun played a valuable part in the matrix for classical art. Reactionary critics, particularly formalists (such as Clement Greenberg on kitsch), refused to accept that play was important in art, declining to take merry pranksters, from Duchamp/ Picabia to Ken Kesey, seriously.

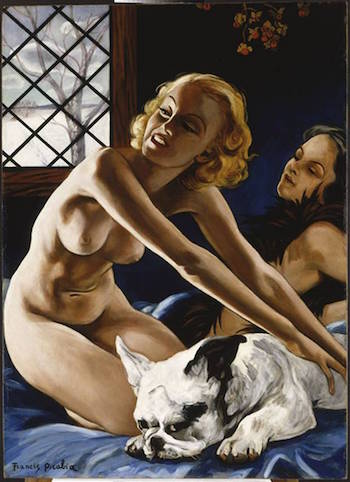

The conundrum Picabia presents is that whatever style he embraced critics automatically slotted him as a lesser or a minor practitioner. This is particularly true of evaluating him as a painter, as he moves from Surrealism to erotic kitsch and then Abstraction.

“Femmes au bull-dog (Women with Bulldog).” Francis Picabia, c. 1941. Oil on board. Photo: Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

In this retrospective there are striking individual paintings, but nothing as riveting as his few, but iconic, Dada achievements. Perhaps a closer look at his non-Dada paintings will promote more concentrated study — and appreciation — of his talent.

Regarding his surrealist pictures, Picabia’s “palimpsest” technique in particular stands out. There are linear layers superimposed on figurative images, a conscious use of juxtaposition that is similar to how Man Ray created photographs through combining negatives (now a part of the Photoshop tool kit). This technique sets Picabia apart from surrealist artists who were obsessed with expressing the visions of the subconscious, either through the inspiration of dreams or automatic drawing. His imagery ranged from neo-classical to grotesque, and that makes some of his paintings tough to like. They are close to the art brut of Jean Dubuffet.

We need to learn more about his work and attitudes during the Vichy occupation. During these years he used soft porn magazines as sources for erotic calendar kitsch. Many of these pictures were sold to a speculator and ended up decorating the walls of North African brothels. There is an uncanny resemblance in these images to the Aryan nudes of Germany’s Nazi artists. What was he up to here? After the war he abandoned figuration and jumped into various forms of abstraction, with mixed results. His ironic (?) sex paintings have been ignored or dismissed by critics, but it turns out that they are essential in understanding the subsequent emergence of pop.

The dilemma when dealing critically with Picabia is that he was not one but many artists. His oeuvre lacks the clarifying cohesion of better known artists. As this exhibition vividly reveals, however, on any given day Picabia was as good as the best of them. He may be the finest modernist you’ve never heard of.

Charles Giuliano, founder/publisher of www.berkshirefinearts.com, is an art historian and former writer/critic/editor for Art New England, The Boston Herald Traveler, Boston After Dark, The Avatar, and The Patriot Ledger. He taught at New England School of Art at Suffolk University, Boston University, Salem State University, UMass Lowell, and Clark University. Since 2014 he has published three illustratred books of poetry.