Visual Arts Review: The Photography of Imogen Cunningham — A Creative Bridge Between Two Worlds

As an artist whose photographs bridge the old world and the new, Imogen Cunningham should be a part of the present-day conversation.

Imogen Cunningham: In Focus. At the Herb Ritts Gallery, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through June 18, 2017.

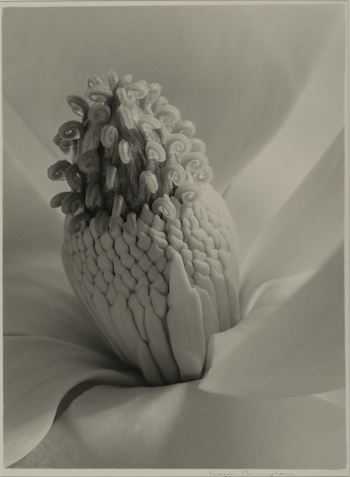

“Hens and Chickens,” before 1929, Imogen Cunningham. Photo: Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By Timothy Francis Barry

“Christ, these hieroglyphs. Here is the most abstract and formal deal of all the things this people dealt out — and yet, to my taste, it is precisely as intimate as verse is. Is, in fact, verse. Is their verse.” from Charles Olson’s Mayan Letters, 1968

Photographs are hieroglyphics. The vintage photographic print, when experienced in the context of a museum exhibition, is in danger of simply degenerating into an artifact, standing primarily as a testament to a distant past, its meanings and power diminished by the passage of time and the inevitable arrival of the new. The evolution of photographic aesthetics elbows aside works that were once thought to be unassailable classics — think of William Henry Fox Talbot, Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Weston, Clarence John Laughlin. Did they produce artworks or antiques?

Hard to decipher, hard to read, these works of the mid-19th through the early 20th century exude poetic resonance, but it is often of the variety of the narcoleptic, inbred verse of Christina Rossetti and A.C. Swinburne. The succeeding group of lensmen (and women) push their elders into an awkwardly antiquated corner. They were inspired by the bop poetics of Frank O’Hara, Diane DiPrima, and yes, Black Mountain bard Charles Olson. We’re talking here about the new photography, the productions of Diane Arbus, William Eggleston, Gary Winogrand, Danny Lyons, an edginess carried forward by Nan Goldin, Alec Soth, Duane Michals, Katy Grannan, and Catherine Opie.

The revered black and white photographs of yore were all about recording the interplay of light and shadow, capturing the pleasant juxtaposition of angle and line, securing for posterity the dignity and charm of its subjects in repose. Or about isolating an element of the physical world, inviting the viewer’s gaze to consider its optical properties rather than its often ambiguous cultural identity. And while those artistic strategies aren’t invalid, they appear to twenty-first-century eyes to be unequivocally dated.

Imogen Cunningham’s black and white vintage prints, as seen in this compact selection from the Lane Collection of Modern American Art, provide a fascinating test-case. Her birth and death dates (1883-1978) roughly mirror those of Picasso and, just as his oeuvre encapsulates the history of modern painting, her career circumscribes the history of photography, right up to the naissance of the 1970’s New Photography movement.

Her earliest efforts — not on view here — share the hazy Whistler-like dreamy quality of Julia Margaret Cameron’s domestic portraits. During the ’20s she was making semi-abstract images of aloes and calla lilies; she examined in photographs what Georgia O’Keefe explored in paint. An image such as 1925’s Exploding Bud (Billbergia) features invaginate plant structures as icons of female sexuality.

A work like 1929’s Hens And Chickens finds her taking up the sort of wholly abstract investigations that would later be pursued by Aaron Siskind and his many progeny. That she picked up and soon discarded such a variety of avenues of artistic exploration sets her apart from many of her contemporaries, most notably her friend Ansel Adams.

By the ’30s she had moved on into territory occupied by Margaret Bourke-White and Charles Sheeler, an undeniably powerful example of which would be 1934’s Fageol Ventilators. In the ’50s she was at the height of her powers, fashioning deeply psychological portraits, such as 1959’s study of poet Theodore Roethke. As the exhibition’s wall-labels note, Roethke suffered from depression. Cunningham’s decision to array him against a graffitied brick wall, looking dazed and tranquilized, is revelatory.

“Magnolia Blossom (Tower of Jewels),” 1925, Imogen Cunningham. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Ironically, the impact of many of the portraits for which she was once effusively praised has lessened. She was lauded for her 1950 portrait of painter Morris Graves, included in this show, along with ‘celebrated’ images she made of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston (members of the f-64 Group of photographers, which she was also a part of). Their stylized preciousness has little to offer today.

One picture that still rewards careful scrutiny is her 1959 portrait of a young African-American, Stan, his hand obscuring part of his face, the latter striated by slats of diagonal light. It is a textbook image of photographic modernism, and could serve as a bridge to the postmodern investigations of a Lucas Samaras or a Robert Heinecken. Indeed, an internet search of Heinecken’s images brings up — on the same page — Cunningham’s Irene (“Bobbie”) Libarry, a 1976 photograph that’s not included in this show. That picture is a direct link to the tattooed endomorphs of Catherine Opie’s visual world.

As an artist whose photographs bridge the old world and the new, Cunningham should be a part of the present-day conversation. That, unfortunately, she’s largely lapsed from popular view is a problem that will not be rectified by this exhibition’s small group of photos. The challenge for photography curators and exhibition organizers is to find ways in which the enduring value of Cunningham, and other ‘poets with cameras’ of yesteryear, can be appreciated now, to help us see them as more than just ‘museum-pieces’ (i.e. defanged and moldy). Clearly, asserting their continuing relevance will be an uphill climb.

Note: The aforementioned Fox Talbot was one of the inventors of photography, though Louis Daguerre would likely arm-wrestle him for the honors; Cunningham’s birth in 1883 overlaps with the end of Talbot’s death in 1887. Talbot’s first and true passion, however, as a world-class Assyriologist with over sixty publications to his name, was the study of….hieroglyphics.

Tim Francis Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, both in Provincetown.

Tagged: Imogen Cunningham, Imogen Cunningham: In Focus, museum-of-fine-arts-boston