Book Review: Patrick Modiano’s Maximal Minimalism

These three books by Patrick Modiano are short, intense, and sensuous, but they might disappoint readers who require plotting, motive clarity, or resolution.

After the Circus, by Patrick Modiano. Translated from the French by Mark Polizzotti. Yale University Press/A Margellos World Republic of Letters Book, 216 pages, Paper, $16.

Paris Nocturne, by Patrick Modiano. Translated from the French by Phoebe Weston-Evans. Yale University Press/A Margellos World Republic of Letters Book, 160 pages, Paper, $16.

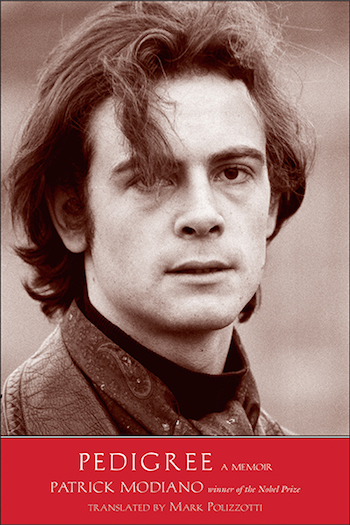

Pedigree: A Memoir, by Patrick Modiano. Translated from the French by Mark Polizzotti. Yale University Press/A Margellos World Republic of Letters Book, 144 pages, Cloth, $25.

Patrick Modiano in Börshuset in Stockholm during the Swedish Academy’s press conference on December 6, 2014. Photo: Frankie Fouganthin.

By David Mehegan

It is risky to generalize about a writer of 16 books on the basis of only four, but since these are all I have to go on, I will say that 2014 Nobel laureate Patrick Modiano is deeply preoccupied with the virtual absence and eventual disappearance of his parents—especially his father—and that his art is saturated with the ache and mystery of their long-ago neglect and its implications for his mature life.

This trio, two works of fiction and a memoir, follow by a year Yale’s edition of Modiano’s Suspended Sentences, three long stories ably reviewed on The Arts Fuse by John Taylor. Yale presumably will bring out Modiano’s other 12 works, a project at least partially funded by the Cecile and Theodore Margellos World Republic of Letters. She is an Athens-based scholar, translater, and critic; he is a Geneva-based financier, evidently with all the yachts and houses he needs. Their objective is to translate into English, and publish, overlooked works of world literature. It is curious that the works of a Nobel laureate should fall in that category; perhaps it would not if he had written about vampires, serial killers, or asteroids hurling toward Earth.

As it is, one can see why American commercial publishers would have passed on Modiano. These three books, and Suspended Sentences, are short, intense, and sensuous, but they might disappoint readers who require plotting, motive clarity, or resolution.

The feeling I get from the Modiano works I have read is that although he is prolific, it is almost as if he not sure that he trusts himself to commit the story to paper. The fiction and, of course, the memoir (of a youthful life which inspired much of the fiction) is all in a singular first-person voice. The voice is beguiling and its narration is thick with precise detail of action, word, and especially locations. (There must be a hundred Parisian streets and addresses named in these books.) What makes it singular is that the narrator acknowledges from time to time that he does not fully understand what is going on; indeed he often avers that his memory or description might be faulty, that he might even be dreaming.

As with any unreliable narrator, we can try to sort it all out. In doing so, we must penetrate a kind of gauzy atmosphere that hangs over everything. It’s all somewhat noir-ish, without noir’s lurid action. It’s not wholly possible to penetrate; the fog never lifts entirely. We have to accept that the object itself might be the painful impossibility of fully recovering our own past or of understanding other people and their acts and intentions.

As After the Circus begins, an unnamed 18-year-old youth is being questioned by some sort of official—whether policeman or other government agent is not clear. The narrator is the youth himself more than 30 years later. The reason for the interrogation: that his name was found in the address book of an unnamed subject of investigation. On his way out after the interview, a girl of about 22 is waiting her turn and enters the interrogation room. He decides to wait for her in a café next door (“on the corner of Boulevard du Palais”), and when she passes by he raps on the window. She comes in and joins him.

It is the beginning of a romance that lasts less than a week, and almost everything about the action is a puzzle to Jean (we learn her name, Gisele, on page 40 and his on page 175), and to the reader. He is poor, practically abandoned by his parents, and wants to avoid military service. Immediately in love with the mysterious Gisele, he wants her to leave the woes and entanglements of Paris behind and go with him to Rome, where he has been promised a job. She likes the idea, but insists they need the help of certain people. She asks him to keep two unopened suitcases in his lodgings, and takes him to visit two men named de Baviere and Ansart, one of them the owner of a restaurant. He does not understand who they are, how they are associated with Gisele, or what it is their game is. There are ambiguous conversations and they question him. Jean becomes uneasy. “I was embarrassed to be the focus of their attention. I started wondering what I was doing there, amid these people I didn’t know. Even she—I didn’t know her any better than the others.”

This question occurs to the reader as well; Jean’s passivity is remarkable and he does not listen to the cautionary impulses within. He reminds me of an expression the pianist Alfred Brendel once used to describe the proper way to play Beethoven sonatas: as if one were being pulled along by a silver cable. He is pulled helplessly along in the same way, though the writing is so spare that we cannot see what is so fascinating about Gisele (so far as I can find, the only given detail of her appearance is blue eyes), why someone he has known for a few days should have such a hold on him. He only says, “I’ve never been very good at saying no.”

Then something happens that would set off anyone’s alarm. Ansart asks a favor: Gisele and Jean are to go to a certain café, go up to a man who will be there (Ansart has photographs so that they will recognize him), and tell him that Ansart is waiting to see him outside. Ansart offers to pay the messengers two thousand francs each. It would seem no person as intelligent as Jean would agree to do such a thing without knowing the reason, but Gisele wants the money, so they can go to Rome, and so of course he agrees.

The encounter happens and they watch outside as the man willingly gets in the car, which drives away. The story moves quickly to its baffling denouement. Another mysterious man—apparently a policeman or other agent—calls him and warns him against Gisele: her name is actually Suzanne, she is a call girl with dangerous associates, he is getting himself in trouble. Of course he does not listen. The fate of Gisele and the Roman plan is abrupt, and like everything else in the book, unexplained.

Paris Nocturne is shorter and equally opaque. Another young man, just short of 21 and remarkably like Jean (but this youth is never named), is walking one night across a Parisian square when he is grazed and knocked down by a “sea-green Fiat.” The woman driver, like Gisele a little older than him, gets out and goes to the hospital with him in the back of a van. A “huge brown-haired man” has appeared and rides with them to the hospital. The youth has surgery under anesthesia, and as he is discharged a few days later, the man appears with a typed description of the accident, absolving the driver of fault. He asks the youth to sign it, which (being a Modiano character), he of course docilely does, then gives him a large wad of money in an envelope.

The accident awakens in the youth, once his head clears a bit, the memory of a similar accident that had happened when he was a child—he was hit by a van—after which he was also taken to the hospital, a young woman beside him in the ambulance. He has the weird feeling that the woman who rode with him that time was the driver of the sea-green Fiat, though in his mind they are the same age, which seems impossible. He begins a quest to find the car, the woman, and the huge brown-haired man. He eventually succeeds, but by now we are not surprised that his discoveries raise more questions than they answer, and the book ends ambiguously.

I read Pedigree, Modiano’s memoir of life up to the age of 21, after the fiction, and I would recommend that order, because it becomes clear that his own young life provides a rich font of feeling and incident for his fiction, and the atmospherics of life and art in both genres is remarkably similar. You find yourself saying, “Ah, here is where that detail came from.” Both parents were what we would call pieces of work, not in the Shakespearean sense. The mother was a failed actress, “a pretty girl with an arid heart. … I can’t recall a single act of genuine warmth or protectiveness from her.” Modiano never gives her name. His father, Albert Modiano, was a rootless schemer and operator with Jewish roots, who by guile and luck barely survived the German occupation. The nature of his various postwar business activities is never clear, but there are hints of shadiness. Both parents, who divorce after the war, keep the boy at an emotional and physical distance, in a succession of boarding schools, his whole childhood. (One thinks of the boy Ebenezer Scrooge.) As he nears maturity, Albert tries to force Patrick into the army.

Patrick has parents but never a real home. As a result, he writes, “I’ve never felt like a legitimate son, much less an heir….I’m a dog who pretends to have a pedigree.” The fate of his mother is never revealed. Only slightly less mysteriously, we are told that in the 1970s, Albert Modiano “went to die in Switzerland, a neutral country.”

Repeatedly in these books, and in Suspended Sentences as well, the narrator doubts his own memory, almost as if he is looking at a movie about his life, shot on such fragile film that he dare not subject it to the kind of bright, relief-revealing light that we might crave. “Today I again see that scene, from a distance,” he writes. “Behind the panes of a window, in muted light, I can make out the blond man in his 50s wearing a plaid bathrobe, a girl in a fur coat, and a young man … The light bulb in the lamp base is too small and weak. If I could go back in time and return to that room, I would change the bulb. But in brighter light, the whole thing might well dissolve.” At these moments of doubt, the narrator often switches from past to present tense, as if he were not actually reporting the past but rather holding a loupe to his present mind. “I would have preferred for us to be in a place that didn’t trigger any past association,” Jean says. “But she said none of that mattered, as long as we were together. We drive down Rue Blanche. Once more, I feel like I’m in a dream. And in this dream, I experience a sensation of euphoria.” There are hints that the exact facts of the past do not matter much. “Nowadays only parrots remain faithful to the past.”

The books are full of large and small echoes. Real-life Patrick had been knocked down by a van as a child. The narrator’s father in the fiction went to Geneva and never returned, as did Albert Modiano. In After the Circus, the man on the phone tells Jean that Gisele’s name is really Suzanne Kray. In Paris Nocturne, the narrator lists the made-up names he and his teenage girlfriend used when they stayed in hotels. One of her names is Suzy Kray. In Pedigree, Albert Modiano has a business crony named Morawski. Near the end of Paris Nocturne, the narrator learns that the huge brown-haired man who appeared after the accident goes by the name of Soliere—but his real name is Morawski.

In all of these works, the city of Paris is a hulking character in the background. Every movement and action occurs in the context of the river Seine, main boulevards and small streets, named cafes at particular addresses and corners, the Louvre and the closed Gare d’Orsay, parks and gardens, innumerable smaller buildings by name and number, many or most of which in the present of the narrator (both novels are narrated 30 years later) have been demolished. The physical scene is rich and fragrant, and clearly represents the narrator’s straining to bring back the moment by means of documentable physical details. And yet here again he is ambivalent. “I probably attach too much importance to topography,” the narrator says in Paris Nocturne. “I had often wondered why, in the space of a few years, the places where I would meet my father gradually moved from the area around the Champs-Elysees toward Porte d’Orleans.” In After the Circus, Jean reports that Ansart’s apartment “was number 14, Rue Raffet. But topographical details have a strange effect on me: instead of clarifying and sharpening images from the past, they give me a harrowing sensation of emptiness and severed relationships.”

Modiano is an immense talent, to be sure. The tone of all these books is poignant and evocative. We read along with fascination. And yet I cannot help but think that all this ambiguity does not necessarily wear well, especially in Paris Nocturne. It is possible, after all, for a writer to omit critical details, logical connections in the plot, and final resolution just because he’s lazy or can’t make up his mind. Paris Nocturne feels half-written. The effect of the style is often mesmerizing, but I’m not sure I want to read 12 more books if they’re all like this.

I cannot help wondering if such comments as these were uttered in the secret precincts of the Swedish Academy. Did anyone say, “OK, I know we have to have a European this time, but is this guy really the best of the bunch?” In Swedish, of course.

David Mehegan is a contributing writer.

Hey, David,

Appreciate your honesty. It respects the reality of the small slivers of reading time I have at my disposal, time not previously committed to reviewing deadlines, etc. The “maximal minimalism” phrase was the clickbait, which worked well enough for me to not just read this but RT, and I enjoyed the piece immensely.

Would I give Modiano a shot, based on your analysis? Yeah, think so. But now he’s right-sized in relation to his reputation, or at least you’ve alerted me to the blinking yellow light ahead, replacing that full-on Nobel-winning green lots of readers assume a writer’s earned, by virtue of the prize.

I’ve just read and reviewed the latest novel by another Nobel Laureate, Kenzaburo Oe, which is why this article caught my eye. All that glitters… It’s too true. Thanks again.”

Now I can rest easily…!

Lisa

Lisa Guidarini

Chicago Tribune Media Group

New York Journal of Books

I have read ALL of Modiano’s books, both in English and Spanish and can’t wait for a new novel of his. His Nobel Prize was long overdue.