Classical Music Album Review: Isabelle Faust and Alexander Melnikov play Brahms

Just about anything Isabelle Faust touches these days is gold – she’s one of the finest violinists out there.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

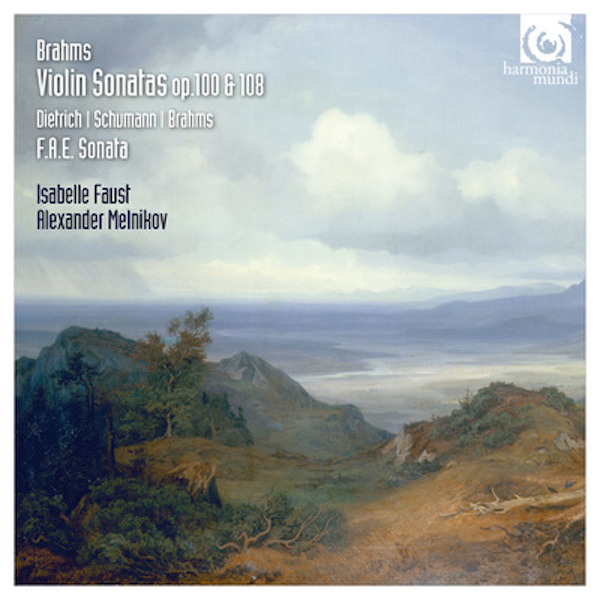

Harmonia mundi’s (HM) hardest-working duo is back at it. Violinist Isabelle Faust and pianist Alexander Melnikov, who (with cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras) have been churning out a Schumann cycle for the label, have a new release that’s thematically related and, like most of their chamber music collaborations, first rate. This new disc pairs the last two of Brahms’ violin sonatas, Schumann’s Three Romances, and the “F.A.E.” Sonata, a score jointly composed in 1853 by Brahms, Schumann, and Albert Dietrich for violinist Joseph Joachim.

The recording starts, chronologically, at the end and works backwards, opening with Brahms’ 1888 Sonata no. 3. It’s a late piece and not a little pessimistic to begin with. In Faust’s hands it’s striking for its grimness and intensity. Her playing in sotto voce passages, especially in the first two movements, demonstrates not just fantastic technical (particularly bow arm) control, but also imbues the music with a haunting character that, in this score, feels appropriate and proves emotionally satisfying. There’s warmth, too, in the second movement and bittersweetness in the third. In the finale, she and Melnikov do a fine job emphasizing the extremes of the music’s dynamics and articulations. The end of the Sonata is shattering but also beautiful, a bit like watching a sunset over a wasteland.

How we (or Brahms) got to this point seems to be the theme of the rest of the album. The earliest piece here certainly doesn’t suggest much by way of emotional turbulence. Schumann’s Three Romances date from 1849 and were originally written for oboe and piano. Sure, they’re filled with plenty of wistful moments but that’s about it, and, in this arrangement for violin and piano, the music fits the Faust-Melnikov duo swimmingly. Their reading of the first movement is a lovely essay in free-flowing melodic playing while the second offers well-balanced contrasts between the dulcet sweetness of the opening theme and the more tempestuous, lively middle section. The finale combines elements of the earlier movements in a warm conclusion.

The second-earliest piece here, the “F.A.E.” Sonata, offers a bit more by way of dramatic variety. Its titled comes from the motto Brahms and his circle of friends had adopted at the time: “frei, aber einsam” (“free, but lonely”) was their quintessentially Romantic creed and, here, the letters provide some of the signal melodic content for the piece.

As an exercise, it’s an interesting, if not wholly successful foray into tag-team composing. Schumann wrote the even-numbered movements, Brahms provided the third, while Dietrich penned the first movement. Elements of Schumann’s Violin Concerto (which he was writing around this time) find their way into his contributions, notably the finale, which is a bit on the stodgy side with lots of writing for violin in its middle- and low registers. The second movement, though, is pretty graceful. Brahms’ scherzo features the most distinctive music in the piece, intense and wild. Dietrich’s installment leaves a bit to be desired: there’s lots going on, material-wise, and, while he was a competent composer, there’s nothing particularly inspired about the way he handles or develops any of it.

Still, Faust and Melnikov turn in a strong reading of the opening movement that’s fairly spacious and, at times, downright epic. Melnikov, especially, plays here with some fierce, rhythmic exactitude. The rest of the performance is lively and engaged, if choppy: good as Faust and Melnikov are, they can’t compensate for the score’s unevenness.

The key to Brahms’ Sonata no. 3, then, appears to be (perhaps unsurprisingly) the Sonata no. 2. In its three movements, it combines the flowing lyricism of the Romances with the jaunty alternations of contrasting materials (and styles) of “F.A.E.” And it points the way forward to something weird and unsettling in its finale.

At least that’s how it comes over in this performance. The first movement sings sweetly but is also marked by some really heroic keyboard climaxes and impressive clarity between the instruments’ various rhythmic textures. Faust and Melnikov mine the second movement’s impish good spirits and they capture the restrained character of the finale impressively. There’s lots of soft, inward playing in the latter that really forces you to listen quietly. And, in so doing, the movement’s structure is illuminated in a revealing, rather disturbing way.

What does it all mean? Well, that’s up to the individual listener to determine, but all the keys you need to solve the riddle are provided. Just about anything Faust touches these days is gold – she’s one of the finest violinists out there – and she and Melnikov have come up with a disc that not only demonstrates their formidable musical chops but also conveys real musical insights and programming intelligence.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.