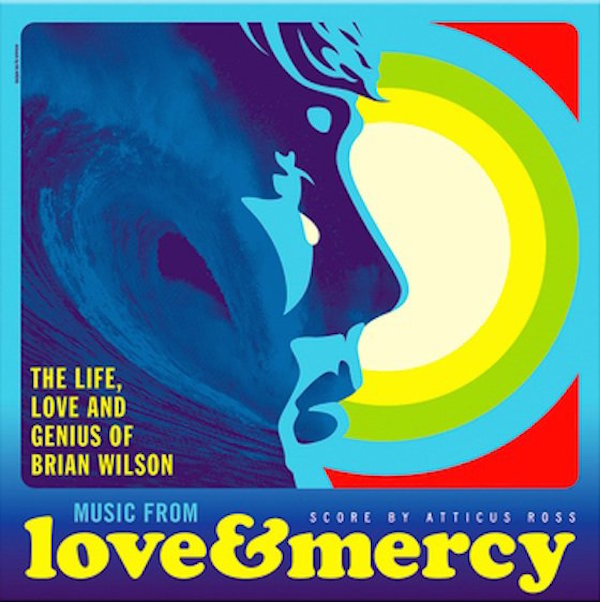

Album Review: Innovative “Love & Mercy” Soundtrack is Worth the Wait

Atticus Ross’ success in creating these pieces results in a listening experience quite a bit more harrowing and evocative than the lush and sunny Beach Boys harmonies people are accustomed to.

By Jason M. Rubin

Love & Mercy, the highly acclaimed indie biopic of the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, widely recognized as one of the great geniuses of pop music, opened in theaters on June 5, 2015, and was released on home video on September 15. The soundtrack CD, which one would expect to be available prior to or concurrent with the theatrical opening, was not released until September 18, due to what director Bill Pohlad called “complications.” Likely it was due to rights issues, since there are excerpts from multiple sources included in the score.

Now that it is here, it is well worth hearing because the album is not what many might expect it to be: yet another collection of Beach Boys songs, of which the market has long since been oversaturated. In fact, only three Beach Boys recordings are presented in full: “Don’t Worry Baby,” “God Only Knows,” and “Good Vibrations” (the lead vocals on the latter two are sung by Brian’s younger brother, Carl). There is also a live version of the title song (which first appeared on Wilson’s self-titled solo album in 1988) from 2002, a much sweeter version than the original, performed by Wilson and his longstanding touring band; and “One Kind of Love” from his most recent solo album, 2015’s No Pier Pressure (the song was awarded Best Original Song when the film showed at the Nashville Film Festival earlier this year).

But the majority of the soundtrack, seven of the 13 pieces, are the compelling collages and compositions of Atticus Ross. In partnership with Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails, Ross has won two Academy Awards: Best Original Score for The Social Network (2010), and Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media for The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (2013). His approach to the Love & Mercy score evolved from discussions with Pohlad, who wanted to bring viewers inside Wilson’s head to hear not only the building blocks of his complex arrangements as they swirled around in his mind, but also to experience the frightening auditory hallucinations that are at the core of Wilson’s mental illness.

Ross’ success in creating these pieces under such a challenging (and subjective) directive results in a listening experience quite a bit more harrowing and evocative than the lush and sunny Beach Boys harmonies people are accustomed to. What is most compelling is that Ross used those very harmonies to alchemize the dark side of Wilson’s story. First he sampled the music, then he morphed and distorted discrete parts so that in many cases they are nearly unrecognizable. He then placed those sound sources in the context of an original composition.

The first of Ross’ pieces, “The Black Hole”, is a short proof-of-concept that introduces the film and his process. It contains portions of six early (pre-Pet Sounds, his 1966 masterpiece) Beach Boys songs, as well as dialogue from the movie and actual audio clips of Wilson working on Pet Sounds in the studio, talking with engineer Chuck Britz and the studio musicians.

His next piece, “Silhouette,” is spookier and contains more original writing by Ross. Featuring samples of four Pet Sounds tracks – “God Only Knows,” “Let’s Go Away for Awhile,” “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder),” and “Sloop John B” – it is mellow in an unsettling way, almost ambient. The word “listen” from “Don’t Talk” (it’s a key moment in the original song if you know it) is harmonized and repeated over and over in a way that is beautiful but hints of obsession and desperation.

As the score (and the movie) go on, it gets more and more disturbing, reaching its zenith (or nadir) in “The Bed Montage,” which accompanies a very powerful moment in the film. At his worst, Wilson spent the better part of three years in bed. Pohlad covers this in a montage that shows Wilson as a boy, as the Pet Sounds auteur (played in the film by Paul Dano), and as the latter-day survivor (played in the film by John Cusack), all alternately occupying the bed and observing the others in it. For this scene Ross wove together highly disparate elements, from a song by the Four Freshman (Wilson’s early idols) to a 1971 Wilson composition, “Til I Die,” that could well have been his suicide note had the very act of being able to compose such a stark expression of one’s own inner turmoil and despair not perhaps have helped to save his life.

Interestingly and appropriately, both “Don’t Worry Baby” and “Good Vibrations” on the soundtrack are sandwiched between Ross pieces, demonstrating the bipolar nature of Brian’s moods and fortunes, the great highs and the gaping lows. The constant back and forth of these states is, in fact, the conceit of the movie, which shifts continuously from Dano’s mid-‘60s Wilson to Cusack’s mid-‘80s Wilson.

As for “God Only Knows,” this might be the soundtrack’s one misstep. First, we hear Dano singing an excerpt of the song, accompanying himself on piano. The actor performs a number of vocals in the film and he does a fine job, one reason why several reviews targeted him as an early Oscar nominee (it has been reported that Wilson himself gave the go-ahead for Dano to sing in the movie after hearing a demo of his voice). However, on the album, the actor’s above-average effort is followed immediately by Wilson’s full-blown production, featuring Carl Wilson’s astoundingly pure lead vocal and his big brother’s masterful arrangement, which inspired Paul McCartney to once proclaim it was his favorite song of all time. Dano’s performance is commendable but next to the original it feels very insignificant.

As a CD, Love & Mercy is short, just 38 minutes long. But that’s still longer than many of Wilson’s most popular albums with the Beach Boys, and had the producers filled it up with more Beach Boys tracks it would have been far too easy to ignore. Here, Atticus Ross’ innovative work takes center stage, and his creations are of a quality that befits their inscrutable subject.

Jason M. Rubin has been a professional writer for 30 years, the last 15 of which has been as senior writer at Libretto, a Boston-based strategic communications agency. An award-winning copywriter, he holds a BA in Journalism from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, maintains a blog called Dove Nested Towers, and for four years served as communications director and board member of AIGA Boston, the local chapter of the national association for graphic arts. His first novel, The Grave & The Gay, based on a 17th-century English folk ballad, was published in September 2012. He regularly contributes feature articles and CD reviews to Progression magazine and for several years wrote for The Jewish Advocate.

Tagged: Atticus Ross, Beach Boys, Bill Pohlad, Brian Wilson, Jason M. Rubin