Dance Review: Alvin Ailey Amplified

There was more than one reference to Alvin Ailey himself in Odetta, recalling Ailey’s frequent use of a female protagonist and his choices of other noted black artists as inspiration.

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, presented by Celebrity Series at the Wang Theater, Boston MA, March 26 through 29.

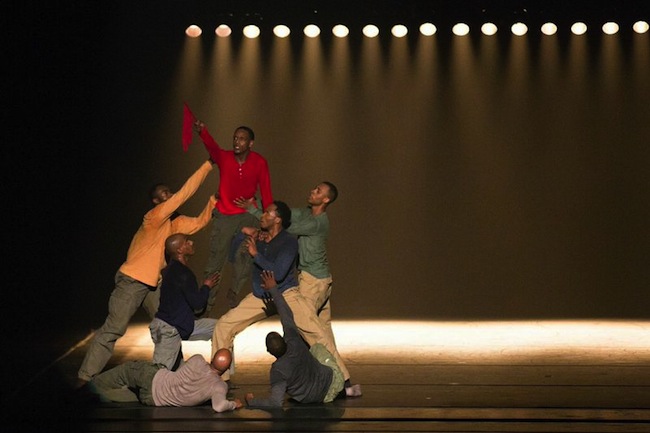

Marcus Jarrell Willis and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in ‘Uprising’ presented by Celebrity Series of Boston. Photo: Robert Torres

By Marcia B. Siegel

Before the first intermission ended at the Wang Thursday night, the audience was stunned by a massive thudding sound. The curtain rose on a bank of floodlights aimed into our faces. As the thudding thundered on, seven men emerged from a smoky void and strode to the footlights, where they stood in a lineup, balancing on one leg. Hofesh Shechter’s Uprising, a 2006 dance recently taken into the repertory of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, was a gorgeous but intimidating mix of movement, sound, and visual display. The dance contrasted an insistent aggressiveness with provisional and potentially erotic comradeship.

The men lurked in the upstage darkness, joined with partners in tight embraces that turned into wrestling holds, walked offstage at will. Keeping their distance, they ran in circles. They scuttled across the stage in a squat, ran crouched over, rolled on the floor, punched the air, squirmed vigorously. Out of the gloom the men formed an inward-facing circle. One man gave his neighbor a jockish swat on the back. The gesture was passed from one man to the next, with increasing vehemence. By the time it got around the circle, the good-guy clout had become a series of whacks. The circle turned into a tumbling brawl. There was more embracing/wrestling, more dragging runs and scrambling punches. Finally the men gathered in a downstage corner, lifting one member who held up a tiny red flag. The machine-shop sound effects dissolved into a few bars of a half-remembered classical symphony. Curtain.

Shechter, an Israeli based in London, works with the movement technique known as Gaga, devised by Ohad Naharin. It’s based in a very physical and aggressive use of the body. Uprising was Shechter’s first choreography – he also created the sound score. I found the dance hard to take with its punishing score, stygian lighting, and relentless pugilism. Perhaps the token red flag was meant as a hopeful sign, but during most of the dance I was thinking about Benjamin Netanyahu and the interminable Middle East peace process. Discouraging, but I guess a seemingly endless discourse of threats and retreats is better than opening fire.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in ‘ODETTA’ presented by Celebrity Series of Boston. Photo: Robert Torres.

If something more positive than a standoff was an afterthought in Uprising, the rest of the opening night performance restored the Ailey’s characteristic hopefulness. Matthew Rushing, now recast from featured dancer to guest artist and rehearsal director, has begun choreographing for the company. His new dance, Odetta, opened the season in Boston.

Hope Boykin in a stunning red dress (costumes by Dante Baylor) played earth mother and spiritual leader to a group of ten communicants. Each of the ensemble members got a featured part to play in a sketch accompanied by the beloved folk singer Odetta, who died in 2008. In a three-part video about creating the dance, Rushing says he was trying to trace Odetta’s life. What little I know about that is her extensive touring, her repertory of folk and gospel songs, and her civil rights activism.

The Ailey company from its earliest days has honored black history and culture in its dances, specifically acknowledging its artistic fathers and mothers. The choreographer provided more than one reference to Alvin Ailey himself in his dance, recalling Ailey’s frequent use of a female protagonist and his choices of other noted black artists as inspiration. Rushing quoted from Ailey’s dances, and his movement seemed derived from everyday gestures; Ailey’s did too, I realized. As in much of Ailey’s work there’s something spiritual underlying even the secular parts of Odetta.

Hope Boykin and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in ‘ODETTA’ presented by Celebrity Series of Boston. Photo: Robert Torres.

Boykin began with a joyful dance, shaking her shoulders and hips, her skirt haloing around her, to Odetta singing “This Little Light of Mine.” Boykin summoned the other dancers, who brought on large wooden set pieces and put them together to make a platform for some danced sermonizing. The set (by Travis George) was taken apart and put together in a variety of shapes during the rest of the dance.

The work continued as a series of loosely connected numbers in varied dynamics. I thought they meant to illustrate the songs, but the recordings were played at such high volume that I often couldn’t make out the lyrics. To “Cool Water” Sarah Daley and Yannick Lebrun performed a pas de deux with more than a little similarity to the now-iconic “Fix Me Jesus” from Ailey’s Revelations. Kanji Segawa did slow balances and unfoldings to “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.” After an anti-war section to “Masters of War,” Megan Jakel danced a kind of tantrum and was brought under control by Boykin as they moved onto a face-to-face mirror duet. Finally, Boykin reconciled the whole group and they gathered to lift her in an Ailey-like cluster of praise.

Revelations closed the program on opening night, as it frequently does. I’ve watched this miraculous dance mutate since its early days, when there were only eight or so dancers at Ailey’s disposal. The cast grew bigger and some of the movement has eased its difficulty. The music has been re-recorded a few times, each time getting more melodramatic, with impossibly extended climaxes and blurred rhythms. To me, the dance looks bloated now, and sometimes automatic. But the performers can still bring the audience to cheers. Maybe that suggests the dance hasn’t lost its integrity after all.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at the Boston Phoenix. She is a Contributing Editor for the Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims–The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983-1996 Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University

Tagged: Alvin Ailey Dance Theater, Celebrity-Series, Marcia B. Siegel, Odetta, Revelations