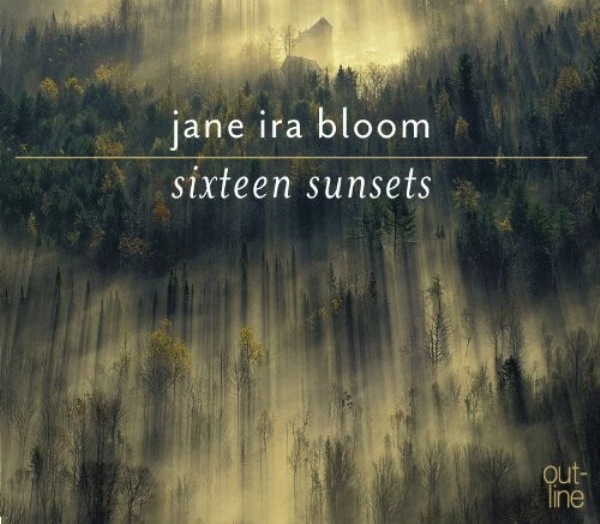

Jazz CD Review / Appreciation: Jane Ira Bloom’s “Sixteen Sunsets” – Jazz Mastery, Undiluted

In nearly 78 minutes of intensely concentrated playing, Jane Ira Bloom’s album offers some of the greatest ballad performances I have ever heard.

Sixteen Sunsets, Jane Ira Bloom (with Dominic Fallacaro, Cameron Brown, Matt Wilson), Outline CD, 2013.

By Steve Elman

Maybe Sixteen Sunsets will finally raise Jane Ira Bloom’s status to that of Major Jazz Artist, elevating her beyond Artist Deserving of Wider Recognition, or whatever other backhanded compliment you might want to substitute for that phrase. In nearly 78 minutes of intensely concentrated playing, this new CD offers some of the greatest ballad performances I have ever heard. It is rich, profound, and deeply moving.

I have known and admired Jane since she brought her first self-produced LP to my long-dead jazz program on WBUR in 1978. That recording (We Are, Outline; duets with bassist Kent McLagan; out of print) was so assured in its identity that I was convinced by it immediately and I knew that she was someone to watch. Since that time, she has made 14 recordings as a leader, and each one has added something valuable to the practice and art of jazz. This new one is the most intimate and the most immediately approachable work she has ever done. It is the perfect place to start if you’ve only heard her name and wonder what she can do.

But let me begin at the beginning, for those who don’t know her at all.

Jane Ira Bloom was born and raised in the Boston area. She now lives and works in New York, where she teaches on the faculty of the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music. She gigs not as often as she would like and almost never plays outside of the New York City area.

Early in her musical career, she decided to concentrate on the soprano saxophone, an instrument which almost always is a second or third axe for a reed player. There are other great stylists on it – Sidney Bechet, Johnny Hodges in his early years, John Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and Steve Lacy. There are a handful of players doubling on it who can tap into its distinctive qualities – Lucky Thompson, Dave Liebman, James Carter, George Garzone, Joe Lovano. There are several figures associated with the avant-garde who have important things to say on it – Evan Parker, Joe Giardullo, Sam Newsome. There is even one person who has become rich by playing it: Kenny Gorelick, known to millions as Kenny G.

Of the few who decided to play soprano exclusively, Lacy, Bloom, and Giardullo are the most notable, and Bloom is the only one who includes a substantial amount of traditional or standard material in her repertoire. She also has built a repertoire of new compositions that range from the strikingly original to the immediately singable, avoiding the opposite pitfalls of abstraction and sentimentality.

Bloom has always had a beautiful tone, perhaps closest to that of Wayne Shorter among saxophonists you may know, but comparison to any other musician does not do her justice. Shorter’s sound is somewhat tighter and more nasal than hers. Coltrane was more of a slash-and-burn player than she is. Bechet’s hot vibrato and jovial brashness are twenties, and Bloom is now. Lacy, the consummate master of the instrument, was restless in his desire to use every sound that could be coaxed out of it without electronics, and Giardullo has followed in Lacy’s footsteps; Bloom plays within the “traditional” margins for the most part, but she has invented a repertoire of electronic and acoustic effects that almost no one else dares to try, because she owns them.

As a technician on her instrument, Bloom has come to the top of the mountain. There are a hundred different ways to attack or release a note; she knows every one of them, and uses every one with the most exquisite taste. She has great microtone control, making some notes a bit sharp or a bit flat, always in the interest of deepening the emotional qualities of the music. Conversely, she can hit any note with absolute purity. She is economical in her pacing, but she is capable of ripping off arpeggios that will thrill you with their drama. She has remarkable consistency and strength of sound from the very highest notes to the very lowest. Within a clean line of notes, she can introduce a tiny bit of buzz on some, a sort of growl in the great tradition of Bubber Miley and Cootie Williams, which she uses to “dirty up” the pretty and make it more muscular. She makes some notes die off sadly and pushes others to ecstasy. And she accomplishes all of this with a dancer’s confidence and grace.

For many years, she has worked to erase the boundary between “tune” and improvisation. Her own compositions are spontaneous and flexible; they allow her to slide into a solo and slide out of it again without defining the edges. When she plays a standard, she does not always feel the need to “take a solo on the changes,” and she can be just as effective by decorating and/or paraphrasing a well-known melody.

As an interpreter of song, a penetrator of lyric, and an intensifier of emotion, she is now approaching the territory inhabited by Miles Davis and Ben Webster. Sixteen Sunsets establishes her absolute control of this landscape, and it establishes a very high fence for any soprano player who chooses to invade it and challenge her. Her statements of melody, her subtle adjustments, and her actual solos are all “sung” without words. Especially in the closing choruses of some tunes, the CD hits amazing emotional peaks, with the intensity of a great lieder singer and the full-throated volume of a great opera singer. There are times between tunes on this CD when it would be wise to stop listening for a few minutes, simply to let your esthetic temperature return to 98.6.

She chooses “For All We Know” as the leadoff, and I cannot think of another version of this song, instrumental or vocal, that is so poetic and heartfelt. The lyric isn’t just about the ephemeral nature of love; it’s about the ephemeral nature of life itself, and Bloom conveys every nuance of that subtext.

She follows it with her deeply affecting original, “What She Wanted,” which tells an extended story without words, poignant and bluesy. The structure of the tune calls for slight increases and decreases in tempo that add narrative nuance. Bloom’s soprano statements, both written-out and improvised, are breathtakingly self-assured here, there’s a lovely short piano solo, and the accompaniment throughout is flawless.

These two tracks alone are worth the price of the CD, but it just goes on and on, going deeper and deeper.

If you doubt how well she can handle tunes that have been done definitively by others, listen to the ones most closely associated with Billie Holiday, “Good Morning Heartache” and “Left Alone.” Bloom has absorbed Billie’s versions and many others, and then set them aside to find her own way through these songs. “Left Alone,” especially, demonstrates how effective she can be – bringing the tune to a wrenching climax and then closing with an a capella cadenza, so effectively stretching the song into emptiness that it was some time before I realized she had decided to echo the title by leaving herself alone in the last few seconds.

Or listen to what she does with George Gershwin’s “I Loves You Porgy.” This is actually her second recording of the tune, and although I love the first one (from Slalom, Enja CD [originally Columbia, 1988]), this one is even better. It’s a duet with her pianist, Dominic Fallacaro, and the two of them concentrate all of the power of a full-bore operatic aria into their chamber version. Like some other tunes in Bloom’s repertoire, this one is preceded and followed by her original piano prelude, which she calls “Gershwin’s Skyline.” It makes the perfect even perfecter.

The title of “Out of this World” suggested something spiritual to John Coltrane, but for Bloom, it taps into an abiding fascination with astrophysics and makes explicit the vision of the CD’s title. In the liner notes, Bloom quotes US astronaut Joseph Allen, who describes the sixteen sunrises and sixteen sunsets that an orbiter of the earth sees in a single day. Bloom brings a musical brightening and fading to the melody of “Out of this World,” floating it over an ostinato by Fallacaro. You can almost see the curvature of the earth.

Another transcendent moment of a different kind is her solo version of Kurt Weill’s “My Ship.” When I asked her about the acoustic effects on this track, she said:

I’ve been recording a capella solos into piano strings since the beginning of my recording career, starting with Second Wind, [Outline, 1980] where I played an intro to “Over the Rainbow.” [The track is entitled “Ten Years after the Rainbow” on the original LP.] I guess it’s become a kind of signature interest of mine over the years. Dominic wasn’t there when I did this solo recording, so we had a sandbag holding down the [piano] pedals. Engineer Jim Anderson also did some magic with the way he was able to isolate and maintain the clarity of the sax sound and the string vibrations.

And the Bloom sweep is here as well. This particular acoustic technique comes from her fascination with dance. She passes the horn across the face of her mic while sounding a note, a trick that is particularly well-suited to the soprano. The resulting phase effect is stunning, and she now uses it with ease and great skill. It especially enriches two of her original tunes on this release, “Ice Dancing” and “Too Many Reasons.”

The three players accompanying Bloom on this CD are not just getting out of her way. She conceived this ballad project in 2011, hand-picked her collaborators, and worked out the interpretations with their assistance in performance.

Pianist Dominic Fallacaro is a real find. Bloom says:

Dominic was originally a student of mine at the New School. I heard something in his playing, his feeling for melody, for ‘less is more,’ that spoke to me from the first time that I heard him.

She’s right. His work has a John Lewis-like delicacy, and like Lewis, he knows that “pretty” doesn’t mean “spineless.” The production keeps his playing natural and soft, not metallic, as in so many modern pickups of the instrument.

Cameron Brown is an exceptional collaborator, and his long partnership as bassist with Sheila Jordan makes him an ideal choice for this very “vocal” instrumental project. His solo on “Left Alone” is a gem, and his support throughout is a model of sensitivity and grace.

And Matt Wilson – funny, daring, subtle Matt Wilson, one of the best drummers to emerge in the past twenty years. He has to limit his volume on this CD for the most part, but that doesn’t mean he’s phoning it in. And on “Primary Colors,” the one up-tempo tune, he shines.

Only one thing could make this CD better: if one of our intrepid local bookers would call Jane up and bring this band to Boston. For now, plan to go to New York in May to see them at Kitano.

I can offer no recommendation higher than this: though Jane was kind enough to send me a free copy of this CD for review, I am about to buy ten copies of it to send to friends. I know they’ll love it, and you will, too.

Steve Elman’s forty-three years in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on WCRB / Classical New England three years. He was jazz and popular music editor of the Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.