Opera Album Review: Offenbach’s “La Périchole,” by an All-French Cast, Combines Zest and Elegance

By Ralph P. Locke

This is one of the zippiest, most life-affirming opera recordings I have heard in a long time. Well, this puts it a bit too blandly, because the work’s social satire also targets the smug self-satisfaction and careless cruelty of the powerful.

Jacques Offenbach: La Périchole

Aude Extrémo (La Périchole), Stanislas de Barbeyrac (Piquillo), Éric Huchet (Don Miguel), Marc Mauillon (Don Pedro), Enguerrand de Hys (First Notary, Marquis), Alexandre Duhamel (the viceroy Don Andrès). Les Musiciens du Louvre, Choeur de l’Opéra National de Bordeaux, conducted by Marc Minkowski.

Bru Zane 1036 [2 CDs] 103 minutes

La Périchole is one of Offenbach’s most frequently performed operettas. The main reason, perhaps, is the first-rate solo music for the title character, a mezzo-soprano role. This woman is known only as Périchole, a nickname whose meaning is obscure—perhaps something like “lowly dog.” Périchole is an impoverished street singer infatuated with her singing partner Piquillo, though she recognizes that he is rather dimwitted (at one point she calls him a fool: nigaud). He is certainly less effective than she at getting café patrons, after a performance, to offer a few coins.

La Périchole is one of Offenbach’s most frequently performed operettas. The main reason, perhaps, is the first-rate solo music for the title character, a mezzo-soprano role. This woman is known only as Périchole, a nickname whose meaning is obscure—perhaps something like “lowly dog.” Périchole is an impoverished street singer infatuated with her singing partner Piquillo, though she recognizes that he is rather dimwitted (at one point she calls him a fool: nigaud). He is certainly less effective than she at getting café patrons, after a performance, to offer a few coins.

Périchole’s four solo numbers have led a lively existence in concerts and on recordings (e.g., by Frederica von Stade and Anne Sofie von Otter). Decades ago I fell in love with recorded performances by Jennie Tourel (including one from a concert at Alice Tully Hall, with Leonard Bernstein a vivid presence at the piano) and by Régine Crespin. In the process, I also became enchanted with those two singers’ voices and performing personalities.

I suppose something similar happened to audience members in Offenbach’s own day. The diva he wrote those songs for, Hortense Schneider, was widely hailed for her singing and acting. Schneider (a native Frenchwoman, despite the German family name) became a kind of muse to Offenbach. He wrote leading roles for her in some of his most renowned stage works, including La belle Hélène (based on the legend of Helen of Troy), Barbe-bleue (Bluebeard), and La grande-duchesse de Gérolstein. “La Snéder” (as she was sometimes called) is reported to have led a scandalous life, including periods of time as mistress to various powerful men. The leading lady’s persona, then, may have added further spice to the plot of La Périchole, in which the heroine agrees, briefly, to enter into a liaison with the viceroy of Peru.

The plot of the work is basically a lark, but making multiple allusions to social attitudes of the day and suggesting possible parallels not just to Schneider but to figures in political life (e.g., Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, who was from Spain). The main characters, besides the two penniless street singers, are the egotistical Spanish viceroy of Peru, who often roams the city in disguise (so he can spy on the populace and also have affairs with beautiful women) and two officials, Don Miguel and Don Pedro, who do his bidding in order to keep their jobs. There is also a drunken marquis, and an aged prisoner (spoken role). Various secondary characters (e.g., notaries and ladies of the court) help move the plot along while also demonstrating much moral shabbiness (e.g., manipulativeness and greed). As so often in Offenbach, the exotic setting—a Spanish-colonial capital in South America—stands more or less for mid-nineteenth-century France.

Briefly, we meet the two impoverished and starving street singers plying their art, to little avail. The viceroy of Peru invites Périchole to become his mistress in the palace. He gets her and Piquillo drunk and arranges for them to marry so he can keep her as his mistress (i.e., not have to marry her). When Piquillo sobers up and realizes that he has married the woman he loves but that she is also supposed to henceforth be the viceroy’s mistress, he objects and is promptly put in a lockup for “recalcitrant husbands.”Périchole visits him, they reconcile, and they are visited by the jailer, who turns out to be the viceroy in disguise and has them put in chains. An old prisoner sets them free. The couple sing one more street song in the public square, after which Périchole offers the viceroy the jewels she had stolen from his palace. The emotionally unstable viceroy, for fear that he might weep at the thought of breaking up such a happy couple, sets the pair free. Everybody joins in a final repetition of the refrain of the second of their three street songs, which was about a conquistador and an Indian maiden: “[The couple’s child] will grow, grow, grow because he is a Spaniard.”

None of the characters, I should make clear, is an “Indian” (i.e., a native Peruvian, descendant of the Incas). But the score contains a quirky, heavy-footed “Indian March” (perhaps with locals being paraded), and Périchole and Piquillo sing the song I just mentioned about a Spaniard, a native woman, and their healthy baby. This song arguably echoes France’s own current-day military conquests and colonial efforts in North Africa and elsewhere. Indeed, the conquistador calls his Indian maiden “Fatma”—a name strongly associated with the Arab world, not Latin America!

The greatest fascination of La Périchole derives from the title character’s behavior, statements, attitudes, and musical choices. Her songs show very different aspects of her personality, depending on what is going on then in the plot. For example, in “Ô mon cher amant, je te jure,” she sings a regretful waltz as she writes a letter bidding farewell to Piquillo (and not quite revealing to him that she has just accepted the viceroy’s offer of a room in the palace). And her “Ah! quel dîner je viens de faire!”—another waltz-song—is usually performed (appropriately) with many hesitations and tempo slow-downs—and perhaps a hiccup or a slurred word or two—to indicate that she is, as she puts it, “un peu grise” (a bit tipsy) from all that wonderful food and wine at the viceroy’s table.

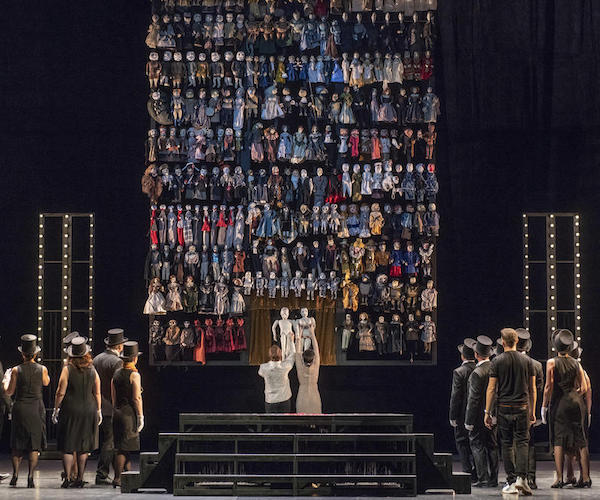

A scene from the production of “La Périchole” recorded by the Bru Zane label (at Opéra National de Bordeaux). Photo: Vincent Bengold.

Piquillo, despite being less alert and strategic than his beloved, does get two fine solo numbers, and these are actually more like true opera arias than any of Périchole’s. The first, an angry “Rondo de bravoure,” is similar to outbursts by many an enraged operatic hero, such as Donizetti’s Edgardo (in Act 2 of Lucia di Lammermoor). It allows the tenor to show off his energetic singing and at least imply that Piquillo is worthy of Périchole’s affection. The second song ends with a particularly touching slowdown (and much gentle orchestral commentary) as he falls asleep in his prison cell.

All the musical numbers are attractive, and there is much stylistic contrast, which adds freshness as the work unfolds. Each of the couple’s street songs, for example, is written in a different manner; the last of them sounding somewhat Middle Eastern, with unexpected chromatic notes and solo oboe—again, perhaps, an allusion to the current-day colonial exploits of France (in North Africa) rather than of Spain. Several of the songs are repeated later in the work, either in their entirety or just the refrain, and often with new words or sung by different characters. Offenbach and his skilled librettists (Meilhac and Halévy, who together would write the libretto for Carmen) knew how to keep surprising us.

Offenbach also offers several numbers that are extensive and elaborate (e.g., the act-finales), and one (at the beginning of Act 2) that would seem of near tragic import to the ear, though the onstage action makes it wholly satirical. We see that four women of the court are trying to awaken a marquis who seems to be in a deep sleep. Given the serious tone of the women’s music, we may well wonder if the marquis has been, say, murdered. He eventually comes to, and—in spoken dialogue—explains that the viceroy’s new mistress kept him awake for hours by her endless loud singing of the refrain to the conquistador-and-Indian-maiden song: “Il grandira (etc.), car il est Espagnol,”

There have been numerous recordings of La Périchole—either entire or condensed—featuring, in the title role, such singers as Régine Crespin, Teresa Berganza, and Maria Ewing, under experienced opera conductors as eminent as Igor Markevitch, Alain Lombard, Michel Plasson, and Marc Soustrot. There was also a one-LP set of highlights, made in 1956, from an English-language production at the Met. That production, which received 71 performances over the next 16 years, was altered musically in basic ways; for example, it reworked the leading-tenor role of the stupid Piquillo to be for baritone, and music was cobbled together to turn the spoken role of the old prisoner into a comic-tenor part. The performance that I saw when the Met came on tour to Boston in the late 1960s featured Teresa Stratas (replacing the production’s original heroine, Patrice Munsel), Theodor Uppman, and, in the barely-needs-to-sing-but-hilarious role of the viceroy of Peru, Cyril Ritchard (the British thespian who played Captain Hook in the beloved TV production of Peter Pan starring Mary Martin). The show was a total delight!

The recording under review was made possible by the Center for French Romantic Music, located at the Palazzetto Bru Zane (Venice). It is the 21st offering in the Center’s series of “CDs+book” devoted to French operas. (The Center also puts out two other CDs+book series: “Portrait” volumes devoted to diverse works by a single composer, and “Prix de Rome” volumes consisting of works written by important French composers, such as Debussy, early in their careers.)

In this new recording, La Périchole returns to its French origins: the singing cast, the conductor, chorus, and orchestra are all French. Les Musiciens du Louvre is an orchestra best known for its recordings of Baroque-era works. (It is now located in Grenoble, though it retains its Parisian name.) The players use period instruments, a fact that here is mainly evident in a sparing use of vibrato and in the solo clarinet’s attractive woodsy sound (or raucous sound in the street songs). Marc Minkowski shows an unerring sense for the perfect tempo and allows the players to phrase a line in a shapely manner or the singers to “point” their words. Together with the recording engineers, he achieves very fine balances between singers and orchestra. (One momentary oddity: in the three humorous statements by an a cappella men’s chorus toward the beginning of Act 2, the harmonies are hard to hear.) There is little noise from the audience, despite the recording’s having been made during live performances. A few moments of quiet chuckling pleasantly indicate some amusing onstage antics.

A scene from the production recorded by the Bru Zane label (at the Château de Versailles Spectacles).

The singers are nearly all splendid vocalists: there is not a wobble heard. Aude Extrémo, who sings the title role, is new to me, and she is a major find! The voice is fuller at the bottom end than that of most other singers who have recorded the role or some of its songs, yet she can soar high with ease. All of this gives her great authority, crucial to the work’s central role of a woman who is decisive and strategic, full of, as we say today, “agency.” Tenor Stanislas de Barbeyrac is much more impressive here than he was as Hylas in John Nelson’s generally admirable (indeed award-winning) recording of Berlioz’s Les Troyens. He can croon gently but finds enough metal to add needed zing to his anger aria. (Click here for Extrémo and Barbeyrac in the lovely Act 3 reconciliation scene, which ends with Péricole’s “Je t’adore brigand.”)

Eric Huchet (as Don Miguel) is particularly wonderful in spoken dialogue, much as he was in the recent recording of Hérold’s Le pré aux clercs. Marc Mauillon (who plays the other courtier, Don Pedro) acts as skillfully as Huchet and sings even a bit better. (The two can be heard fake-flattering Piquillo in the Act 3 duet in bolero style: Huchet sings first.) Enguerrand de Hys is a vivid performer, as he was in Salieri’s Tarare, in two roles (one spoken). Only Alexandre Duhamel disappoints a bit, as the viceroy. He has a firm, clear voice (as can be heard in his Act 3 trio with Périchole and Piquillo), but he doesn’t “act” much with it during the sung portions. He is quite effective in the spoken dialogue, though.

It helps that all the singers are native French-speakers. In the musical numbers, they maintain a beautiful line and excellent breath control while still conveying an immense range of emotional tones. When the spoken dialogue begins again, they are like ponies let out of a stable, full of spirit and ready to play. This is a recording that will wear well for years, though some listeners may prefer at times to skip the spoken tracks.

The recording was made over the course of several staged performances that took place in 2018 in the renowned theater/opera house in Bordeaux, an intimate hall (1000 seats) dating back to 1780. (Moments from the production are shown in this short video.) Applause, wildly enthusiastic, has been mercifully edited down to a minimum. Scenes of spoken dialogue sometimes go on for several minutes—in one case, ten. The dramatic pace is often swift, and, though my French is not bad, I did sometimes have recourse to the book’s libretto and its (generally very capable, occasionally too literal) translation in the hardcover book that comes with the two CDs. Other times, I didn’t need to peek, because the way a character spoke the lines—huffily, condescendingly, irritatedly, and so on—allowed me to imagine specific facial expressions, hand gestures, or some eloquent shoulder-shrugging. There are a few quasi-improvised added touches, some intentionally anachronistic, such as a reference (in the dialogue) to The Merry Widow (1905). Some of these small changes are incorporated without comment into the printed libretto—don’t be fooled!

Another scene from the production recorded by the Bru Zane label (at Opéra National de Bordeaux).

The accompanying book contains three highly informative and wittily written essays, all of which deepen our understanding of this endlessly fascinating work. In four respects, though, the book is more frustrating to use than is usually the case with releases from the Center (at the Palazzetto):

1) In the process of editing the libretto to match what is heard, some helpful or even crucial stage directions have disappeared (such as that, as noted above, in the middle of Act 3 the viceroy puts Périchole and Piquillo in chains).

2) In different places in the essays and listings, a character may be referred to by any one of several different names. It took me a while to figure out that Hinoyosa, Don Pedro, the Mayor of Lima, and the Gouverneur are all the same person.

3) When musical numbers of the 1868 and 1874 versions of the work are mentioned, the writers may give the original numbering in the respective version but never refer to the track number in the recording. This creates trouble for a reader trying to locate a given song or larger ensemble or even to figure out if it has been omitted. Quick summary: the recording largely presents the longer version, from 1874, which added the very effective prison scene at the beginning of Act 3. But it removes four numbers from the act. This all works just fine: even after repeated listenings, I didn’t feel that the show had any glaring holes in it. Still, I was glad to go back to some older recordings to enjoy the music omitted here.

4) For the essays, the translator should have allowed himself much more freedom, clarifying literary allusions and expanding certain highly condensed phrases. Does “Si le grain ne meurt”—a section heading in one of the essays—refer to the parable in John 12:24, the famous novel by André Gide, or both? (The section in question treats differences between the libretto and its main source: a comic play by Prosper Mérimée.) The English heading reads simply “If the Grain Doesn’t Die.” Literary French cannot be transported word-for-word into English. Sometimes these essays simply cry out for an expanded wording in our language, or even for explanatory footnotes.

But I don’t wish to end on a carping note. This is one of the zippiest, most life-affirming opera recordings I have heard in a long time. Well, this puts it a bit too blandly, because the work’s social satire also targets the smug self-satisfaction and careless cruelty of the powerful.

La Périchole is French as all get-out. I recommend it with a good vin rouge, a ripe Camembert, a fresh baguette, and maybe a chunk of imported Peruvian chocolate with red-pepper flakes.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and the Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Bru Zane, Center for French Romantic Music, Jacques-Offenbach, La Périchole, Marc Minkowsk